“I’ve been bored too long. I can’t stand it any more. I’m too rich to work, too intelligent to play—much. I tell you, if something doesn’t happen within the next few days, I’ll explode.” — Bulldog Drummond

The movie private detective Bulldog Drummond has a long history, equal to most of the other sleuths who were more or less his contemporaries in the 1930s and ’40s—Charlie Chan, the Crime Doctor, Philo Vance, the Thin Man and a host of others. They owe a considerable debt to nineteenth-century writers who originated the fictional detective—Edgar Allan Poe (The Gold Bug and Murders in the Rue Morgue), even Charles Dickens (the uncompleted Mystery of Edwin Drood) and, of course, the most recent of these, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle whose Sherlock Holmes adventures began in 1886 with A Study in Scarlet.

As suggested, British writers, many of them women, seemed to have had an edge on the detective genre, soon known as the masters of the drawing room mystery, where mental deductions and armchair sleuthing were the rule over physical action. The best known writers include Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, G. K. Chesterton and, most recently, the late P. D. James. And Herman C. (“Sapper”) McNeile, a World War I veteran born in Cornwall, England, created the first of ten Bulldog Drummond novels in 1920.

The screen Drummond, like some of the other series, had a variety of actors playing the detective. Both the British and Americans had a go, including Ralph Richardson, Ray Milland, John Barrymore, Tom Conway (though better known for the Falcon series) and John Howard, as well as Australian Ron Randell and Canadian Walter Pidgeon.

The screen Drummond, like some of the other series, had a variety of actors playing the detective. Both the British and Americans had a go, including Ralph Richardson, Ray Milland, John Barrymore, Tom Conway (though better known for the Falcon series) and John Howard, as well as Australian Ron Randell and Canadian Walter Pidgeon.

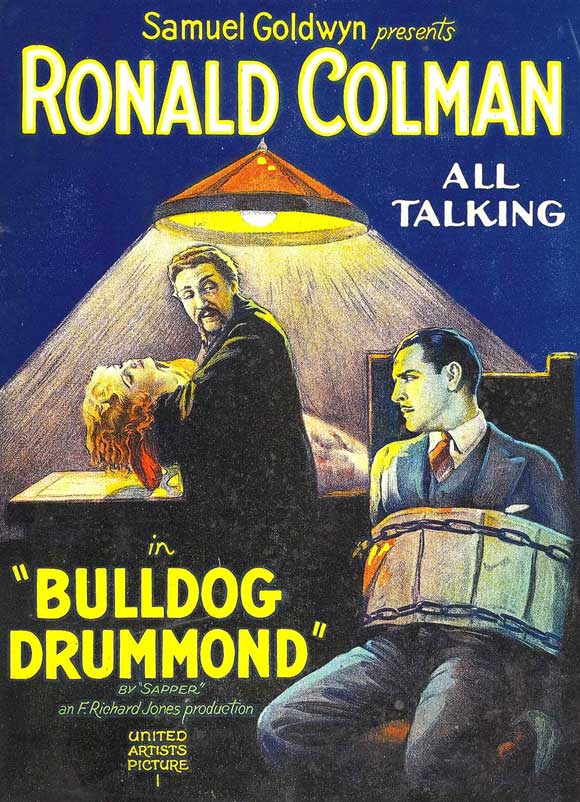

The obvious Bulldog Drummond actor missing from this list is Ronald Colman, who made the first sound version of a Drummond mystery, Bulldog Drummond, in 1929. It was also his first sound picture. While the film has a largely British cast, except for two Americans, heroine Joan Bennett and baddie Lilyan Tashman, it is stoutly American in its production. It was the last film for director F. Richard Jones, who, like Tashman, died in his mid-thirties. Sidney Howard (Gone With the Wind, 1939) wrote the screenplay, which, in the opening credits, is quaintly “adapted for the talking screen.” The dual cinematographers are George Barnes (Rebecca, 1940) and Gregg Toland (Citizen Kane, 1941). Set decoration is by none other than William Cameron Menzies, best remembered for Wind and, as director, for Things to Come (1936). (In 1934, Colman would star in a sequel, Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back, with Loretta Young.)

Despite those previous decades of silent films, Bulldog Drummond avoids most of the trappings and techniques of that era—it is, in fact, one of the best of the early talkies. But, with sound still in its infancy, and with many improvements yet to be made, the film cannot entirely divest itself of the past.

For one thing, it is basically set-bound, although one of the best camera shots—chiaroscuro and all (Toland, Barnes or both?)—is the night “exterior” (probably a set) of a tall, castle-like nursing home. Tashman’s general delivery and mannerisms, with eyes cast melodramatically here and there, are leftovers from the previous style of acting when stars had to exaggerate expressions to compensate for the lack of a voice.

For one thing, it is basically set-bound, although one of the best camera shots—chiaroscuro and all (Toland, Barnes or both?)—is the night “exterior” (probably a set) of a tall, castle-like nursing home. Tashman’s general delivery and mannerisms, with eyes cast melodramatically here and there, are leftovers from the previous style of acting when stars had to exaggerate expressions to compensate for the lack of a voice.

Movie-goers are now so accustomed to a musical soundtrack that the absence of one leaves an obvious vacant space waiting to be filled. Colman and Bennett’s romance, however, is so tepid and undeveloped that any romantic music is hardly missed. There is main title music and a few seconds of “The End” music. The not-bad Viennese waltz used in both was possibly composed by the music director, Hugo Riesenfeld. It’s conceivable: he was born in Vienna and had quite an impressive music résumé prior to his appointment, in 1928, as director of all music productions for United Artists.

The Drummond story is so quick-paced and Ronald Colman so active—one wonders whether he adapts to the tempo or sets it—that much of the time the music is unmissed. Joan Bennett, by contrast, is a little low-key and underplays her role, though she was perhaps never lovelier, only nineteen at the time.

After some stock footage of London landmarks, the camera enters a men’s club where silence, with an exclamation, is an imperative. In a long tracking shot, an attendant conveys a serving tray through a lobby of elderly men reading newspapers and books in their isolated nooks. He drops a spoon, prompting an outcry from a patron.

After some stock footage of London landmarks, the camera enters a men’s club where silence, with an exclamation, is an imperative. In a long tracking shot, an attendant conveys a serving tray through a lobby of elderly men reading newspapers and books in their isolated nooks. He drops a spoon, prompting an outcry from a patron.

At a corner table are two men. One (Claud Allister) wears a monocle and tilts his head back, giving the impression of looking down his nose, a semblance to aristocratic pomposity he will maintain throughout the film. “That’s the third spoon I’ve heard drop this month,” he says with a la-di-da inflection to his British accent.

The second man, wealthy Captain Hugh Drummond (Colman), a veteran of World War I, disagrees with his best friend, Algy Longworth. “I wish somebody would throw a bomb and wake the place up.” Followed by Algy, he walks out of the room whistling, to the shock of the old men. In a later film, Top Hat(1935), Fred Astaire does a brief tap-dance in another snobby Englishman’s club.

A drink at the club’s bar, Drummond says, hasn’t made him feel better, that he’s bored. When Algy suggests he advertise for excitement, he puts an ad in the newspaper. One reply offers possibilities, and he sets out for the Green Bay Inn where a young woman, Phyllis Benton (Bennett), fearing she’s in danger, has reserved a room for him. Algy follows in a second car, accompanied by Drummond’s valet, Danny (Wilson Benge).

A drink at the club’s bar, Drummond says, hasn’t made him feel better, that he’s bored. When Algy suggests he advertise for excitement, he puts an ad in the newspaper. One reply offers possibilities, and he sets out for the Green Bay Inn where a young woman, Phyllis Benton (Bennett), fearing she’s in danger, has reserved a room for him. Algy follows in a second car, accompanied by Drummond’s valet, Danny (Wilson Benge).

Phyllis tells Drummond that something is amiss at a hospital where her wealthy uncle, John Travers (Charles Sellon), is being treated by Dr. Lakington (Lawrence Grant).

Later, she mistakes the silhouette of Algy and Drummond for the people she believes are following her and runs away, only to be caught my Dr. Lakington, Irma (Tashman) and Carl Peterson (Montagu Love), and taken to the doctor’s nursing home.

Drummond follows, knocks on the door and conducts a rather civil conversation with the culprits, but he sees how Travers is being treated for what the doctor vaguely identifies as a psychological illness. Drummond affably says good-bye, as if his suspicions aren’t aroused.

Drummond follows, knocks on the door and conducts a rather civil conversation with the culprits, but he sees how Travers is being treated for what the doctor vaguely identifies as a psychological illness. Drummond affably says good-bye, as if his suspicions aren’t aroused.

He drives off, stops a short distance down the road and sneaks back to the nursing home to rescue Phyllis, sending her off with Algy and Danny. He then eavesdrops on the resident trio who try to force Travers to sign over to them his jewels and securities.

After now rescuing Travers, Drummond returns to the inn, but the criminals have followed him. He quickly disguises himself as Travers, and the unsuspecting crooks take him to the nursing home. When they do realize it’s Drummond, they tie him up and threaten to torture Phyllis to learn Travers’ hiding place. Drummond says Travers is at the inn, and while Irma and Peterson go to check, Phyllis frees Drummond. In a struggle, Drummond strangles the doctor.

After all this running around—many scenes of cars racing back and forth in the night—Peterson now returns. Drummond disarms him and calls the police, but the policemen who come are Peterson’s gang in disguise. While calling the real police, Phyllis persuades Drummond to let Peterson go, confessing in a soft, meek (unconvincing?) voice that she loves him.

After all this running around—many scenes of cars racing back and forth in the night—Peterson now returns. Drummond disarms him and calls the police, but the policemen who come are Peterson’s gang in disguise. While calling the real police, Phyllis persuades Drummond to let Peterson go, confessing in a soft, meek (unconvincing?) voice that she loves him.

“Why haven’t you ever said that before?!” he asks, as he puts down the receiver to embrace her.