“I’d be a much happier man if I’d never met you.” — Ronald Brooke

“I’d be a much happier man if I’d never met you.” — Ronald Brooke

Of the three films they made together, all screwball comedies, Joan Blondell and Melvyn Douglas had their best pairing in Good Girls Go to Paris. The year before, in 1938, they had starred in There’s Always a Woman, a husband and wife comedy-mystery, and later that same year Douglas reprised his role as detective Bill Reardon in There’s That Woman Again, only now his wife was Virginia Bruce. The two films had the same zaniness, but Blondell’s magic and the chemistry with Douglas were missing in the sequel.

In the early part of his career, Douglas appeared in horror films—James Whale’s The Old Dark House(1932) being the best—and detective capers. His only appearance as the Lone Wolf was to launch the series in 1938 with The Lone Wolf Returns—the “return” heralding the first sound Wolf film since the silent days. Most often, however, Douglas settled into romantic leads, often tuxedo-attired, playing opposite such ladies as Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford and Claudette Colbert.

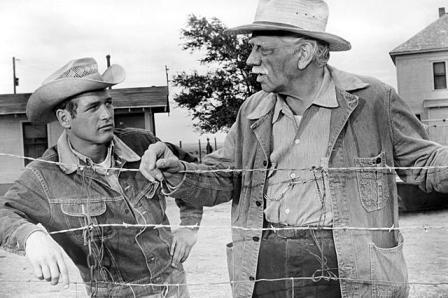

During much of his early Hollywood career, Douglas said he was bored by his “one-dimensional and non-serious roles.” It was only when he began character parts in his sixties, this coinciding with the decade of the 60s, that he found meatier parts worthy of his talents. He received a Best Supporting Actor Oscar portraying the decent father of the amoral Paul Newman in Hud (1963). The next year, in The Americanization of Emily, he was loony Admiral William Jessup, insisting that the first dead man on a D-Day beach must be a U.S. sailor, foreshadowing another loony military Jessup, U.S. Marine colonel Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men (1992).

During much of his early Hollywood career, Douglas said he was bored by his “one-dimensional and non-serious roles.” It was only when he began character parts in his sixties, this coinciding with the decade of the 60s, that he found meatier parts worthy of his talents. He received a Best Supporting Actor Oscar portraying the decent father of the amoral Paul Newman in Hud (1963). The next year, in The Americanization of Emily, he was loony Admiral William Jessup, insisting that the first dead man on a D-Day beach must be a U.S. sailor, foreshadowing another loony military Jessup, U.S. Marine colonel Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men (1992).

In 1970, Douglas was nominated Best Actor in I Never Sang for My Father, about an insensitive, then ill, father of Gene Hackman, and in 1979 the actor received his second Best Supporting Actor Oscar as a bed-ridden business man in Being There (1979), influenced by an inept Chauncey Gardner (Peter Sellers) taken for a political pundit.

That Melvyn Douglas might have been bored in his role in Good Girls Go to Paris isn’t apparent. He’s debonair, a smooth operator, his hair and clothes never rumpled, the dinner jacket, drawing room type. His dignity is threatened, sometimes to the point of controlled exasperation, by the antics of a waitress who comes into his life. She never seems able to tell the truth and leads him into all sorts of confusing and compromising situations.

Douglas’ co-star and, really, the only other actor in Good Girls Go to Paris who makes any striking impression, is the animated Blondell, one of the masters of the screwball comedy. If Douglas adds the dignity and a center of gravity, however tenuous—he’s almost stiff by comparison—Blondell sets the tempo and provides, all at the same time, the effervescence, charm and craziness that keeps him, and the plot, wonderfully off balance. This appealing mixture is found in few actresses.

Walter Connolly seems counterproductive to the best interests of the film. Known for over-the-top acting, his delivery is often loud and without nuance. He is best remembered for It Happened One Night(1934) as Claudette Colbert’s father, who is about to give her away at her wedding when she runs off to the man (Clark Gable) she really loves. In Good Girls Go to Paris, Connolly rehearses giving away his granddaughter for a wedding that never happens.

Walter Connolly seems counterproductive to the best interests of the film. Known for over-the-top acting, his delivery is often loud and without nuance. He is best remembered for It Happened One Night(1934) as Claudette Colbert’s father, who is about to give her away at her wedding when she runs off to the man (Clark Gable) she really loves. In Good Girls Go to Paris, Connolly rehearses giving away his granddaughter for a wedding that never happens.

An exchange professor from England, Ronald “Ronnie” Brooke (Douglas), arrives to conduct his first class in Greek mythology. Born in Macon, Georgia, Douglas makes no attempt to sound British, except for the occasional long “a.”

In a hallway on his way to his classroom, Brooke casually mingles with some young men who assume he is a fellow student and expect their professor will be a “grumbling old fluff,” with a “long, white beard.” The students, expecting an easy course, are surprised when Brooke walks in as their professor. He uses the incident in the hall as an example of an Aesop fable—the wolf in sheep’s clothing—and warns that, at end of term, they must pass a rigorous exam.

In the university’s restaurant, Brooke is attended by waitress—not “server”; this is the 1930s—Jenny Swanson (Blondell), who demonstrates how to dunk a tea bag in his cup of hot water. Accustomed to proper English tea etiquette, he responses, “And then you . . . drink it?” In It Happened One Night, Gable had shown wealthy socialite Colbert how to dunk a doughnut.

In the university’s restaurant, Brooke is attended by waitress—not “server”; this is the 1930s—Jenny Swanson (Blondell), who demonstrates how to dunk a tea bag in his cup of hot water. Accustomed to proper English tea etiquette, he responses, “And then you . . . drink it?” In It Happened One Night, Gable had shown wealthy socialite Colbert how to dunk a doughnut.

Later, when Jenny has explained to Brooke how she plans to earn a trip to Paris by blackmailing some handy rich man’s son, he warns her with another Aesop fable. Seems a sick lion asks a fox to come into his cave and hold his paw, but the wise fox notices that the animal tracks leading into the cave never lead out. “Never venture into anything,” Brooke says, “unless you can see your way out.”

Literally moments later, she is almost run over by Ted Dayton’s (Stanley Brown) speeding roadster and is understandably upset until he mentions his rich father. She says she needs a ride and jumps in his car.

In her first effort to get to Paris, she attempts to blackmail Ted’s father (Clarence Kolb), saying she has his son’s letters of proposal in her purse, but when she doesn’t produce them, the father threatens to call the police unless she leaves town.

On the way out of town to her home in Maple Leaf, Missouri, Jenny stops in to see Brooke. She tells him she “forgot about the sick lion and walked right into his den.” She didn’t show the letters, she says, because she remembered his warning, which caused a funny feeling in her stomach. He explains it’s a “flutter,” her conscience talking, and reminds her that “good girls go to Paris, too.” After giving her a book of Aesop fables, he says he will soon finish his lectures and leave for New York to marry Sylvia Brand (Joan Perry), then return to England.

At the train platform—here happenstances really begin!—Jenny accidentally meets Tom Brand (Alan Curtis), Sylvia’s rich playboy brother, on his way to New York for her wedding. Seeing in Tom another way to Paris, Jenny buys a ticket for New York instead of Maple Leaf.

At the train platform—here happenstances really begin!—Jenny accidentally meets Tom Brand (Alan Curtis), Sylvia’s rich playboy brother, on his way to New York for her wedding. Seeing in Tom another way to Paris, Jenny buys a ticket for New York instead of Maple Leaf.

In New York, Tom and Jenny go nightclubbing and meet Sylvia with Dennis Jeffers (Henry Hunter). Eavesdropping, Jenny learns that Sylvia is in love with Dennis, not Brooke, and that Tom has a gambling debt. Also present is Sylvia’s mother Caroline (Isabel Jeans), out with boyfriend Paul (Alexander D’Arcy), a gold-digger himself.

The by now drunk Tom takes Jenny to the family home and she puts him to bed. In slipping out, she meets Caroline slipping in. They awaken the ailing grandfather, Olaf (Connolly). When Olaf loudly inquires about this stranger, Caroline improvises that Jenny is one of Sylvia’s bridesmaids.

Jenny quickly makes herself a part of the family and begins winning over Olaf with a Swedish remedy for his sore throat. One morning when the household assembles for breakfast, Sylvia is flabbergasted to find that Jenny, this stranger, is an “old friend from college,” and Brooke, who has arrived, is surprised to find Jenny is a guest in his fiancée’s home. Both Sylvia and Brooke play along.

Jenny quickly makes herself a part of the family and begins winning over Olaf with a Swedish remedy for his sore throat. One morning when the household assembles for breakfast, Sylvia is flabbergasted to find that Jenny, this stranger, is an “old friend from college,” and Brooke, who has arrived, is surprised to find Jenny is a guest in his fiancée’s home. Both Sylvia and Brooke play along.

The climax, although less civilized and scattered over numerous scenes, is reminiscent of the kitchen scene, the gathering of all the characters in Moonstruck (1987). A Mr. Schultz (George Lloyd) comes to collect Tom’s $5,000 gambling debt, but Jenny promises to pay him the next day, so Olaf won’t learn of it.

Earlier, when Sylvia was in Dennis’ car and his driving had injured a man, she had identified herself as Jenny Swanson to avoid a scandal. Now, when Sylvia asks Jenny to take the blame, Jenny demands $5,000 for her silence—money for Tom’s debt. As for Paul and Caroline’s planned elopement, Jenny exposes Paul as a leech out for her wealth, and Sylvia receives Olaf’s approval to marry Dennis.

After these couples have paired off, Brooke proposes to Jenny: “England, while the climate is not all that it should be, is very well known for honeymoons and has the added advantage of being just across the Channel from Paris.” So, you see, good girls do go to Paris!

The end is much, much more complicated than here described—and much funnier, with Connolly, in his best moment, bewildered by the confusing family revelations. A movie fan has to see the film to perceive all the, let’s say, “subtleties,” if that’s the word, and to appreciate this crazy comedy. Screwball, it certainly is!

The end is much, much more complicated than here described—and much funnier, with Connolly, in his best moment, bewildered by the confusing family revelations. A movie fan has to see the film to perceive all the, let’s say, “subtleties,” if that’s the word, and to appreciate this crazy comedy. Screwball, it certainly is!

Judging by Good Girls Go to Paris, it’s not obvious that the year of its release, 1939, was Hollywood’s greatest year. The number of memorable pictures, including Stagecoach, Dark Victory, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Wuthering Heights, Good Bye, Mr. Chips and, of course, Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, would never be equaled again, or even approached.

Appearing in one of the last years of the long Great Depression that had begun in 1929, Good Girls Go to Paris, is, however, representative of its era, the ’30s, when one point of the screwball comedy, like the concurrent Busby Berkeley musicals, was to lift the spirits of the American people out of their troubles. In that regard, the film succeeds admirably, coincidences, implausibilities, silliness and all, thanks mainly to the sparkling appeal of Joan Blondell and the stabilizing anchor of Melyvn Douglas. Not a masterpiece certainly but a fitting movie for late-night insomnia. If it doesn’t cure the insomnia, the film is still a suitable diversion until the dawn breaks.