“Sure, I may be tuckered, and I may give out, but I won’t give in.”— Molly Brown

Quality Hollywood movies somehow increased in 1964, and one of the best years of the decade offered a little more variety than usual. Dr. Strangelove shocked as an imaginative black comedy about two superpowers on the brink of world destruction and The Night of the Iguana did its own shocking with alcoholism and repressed—and expressed—sexual passions. Becket as a serious historical, Shakespeare-like drama portrayed a king and his wayward archbishop and Zorba the Greek made high cinema of an earthy peasant. The Pink Panther offered the greatest contrast of the four; to an unsuspecting world, it introduced the bumbling Inspector Clouseau and his personification in one Peter Sellers.

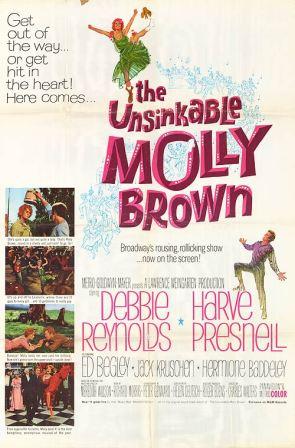

Being in the center of a decade of extravagant musicals, 1964 alone produced three competitive song and dance films—Mary Poppins, My Fair Lady and The Unsinkable Molly Brown. In most of the Oscar categories two of them, sometimes all three, were nominations. When a musical won, which was thirteen times, it was never The Unsinkable Molly Brown.

And its nominated Best Actress star, Debbie Reynolds, lost to the favorite, Julie Andrews, for Mary Poppins. It would be Reynolds’ only Oscar nomination, though she received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the 2015 Oscar ceremonies, February 28, 2016, belatedly extended by the Academy, as usual for elderly, Oscar-less stars. But even that was none too soon, for Reynolds died on the twenty-eighth of another month, December 2016.

And its nominated Best Actress star, Debbie Reynolds, lost to the favorite, Julie Andrews, for Mary Poppins. It would be Reynolds’ only Oscar nomination, though she received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the 2015 Oscar ceremonies, February 28, 2016, belatedly extended by the Academy, as usual for elderly, Oscar-less stars. But even that was none too soon, for Reynolds died on the twenty-eighth of another month, December 2016.

She is perky and high-stepping in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), easily her most popular and best film, and one of the greatest musicals of all time. Untrained as a dancer, Reynolds was highly tutored by Gene Kelly, co-director with Stanley Donen. She shared her choreographic routines with another light-footed elf, Donald O’Connor, and no one would have ever imagined she wasn’t a professional dancer from the start.

In The Unsinkable Molly Brown, music and lyrics by Meredith Willson, she is more than a mere “high-stepper”: she is a keg of dynamite about to explode. She is loud, common and vulgar, until she transforms her character into a lady—well, only partially—and seeks a place in the upper echelons of society. There, at first, she finds only snobbery and exclusion, but determined—and “unsinkable,” as it will prove—she triumphs and receives all she ever desired during her poverty days.

Although Debbie Reynolds’ supporting cast members are all competent and throw themselves with wild abandon into some of the crazy antics of the film, she has only one serious co-star, one fellow singer of stature, Harve Presnell. There is obvious chemistry between her and this six-foot-five-inch, gangling actor, who never competes with but compliments Reynolds with his quite different acting and singing style.

Although Debbie Reynolds’ supporting cast members are all competent and throw themselves with wild abandon into some of the crazy antics of the film, she has only one serious co-star, one fellow singer of stature, Harve Presnell. There is obvious chemistry between her and this six-foot-five-inch, gangling actor, who never competes with but compliments Reynolds with his quite different acting and singing style.

Unfortunately, Presnell’s career faltered in the closing years of the decade, when the vogue for musicals, reaching a pinnacle with The Sound of Music in 1965, was fading, at least for a while. Doctor Doolittle (1967) and Hello, Dolly! (1969) were among several singing disasters. In Paint Your Wagon(1969), sluggishly directed by Joshua Logan, Presnell is the only professional vocalist among such non-singers as Clint Eastwood, Lee Marvin and Jean Seberg, though she, fortunately, was dubbed (by Anita Gordon).

A baby, surviving the rapids of the Colorado River, is adopted by frontiersman Shamus Tobin (Ed Begley, Best Supporting Actor Oscar two years earlier for Sweet Bird of Youth) and given the name Molly (Reynolds). Molly becomes a tomboy, dresses in trousers and a shabby shirt and uses foul language.

A baby, surviving the rapids of the Colorado River, is adopted by frontiersman Shamus Tobin (Ed Begley, Best Supporting Actor Oscar two years earlier for Sweet Bird of Youth) and given the name Molly (Reynolds). Molly becomes a tomboy, dresses in trousers and a shabby shirt and uses foul language.

Her fight with Shamus’ three sons produces a rip-roaring “I Ain’t Down Yet,” and between lyrics she expresses her philosophy: “I hate the word ‘down,’ but I love that word ‘hope,’ ” and “I mean much more to me than any one I ever knew.” Soon, though, Molly believes it’s time to leave, with two objectives, to learn to read and write and to marry a rich man.

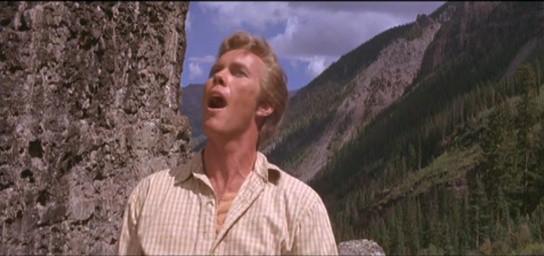

Against a sumptuous mountain landscape, the owner of a gold mine, Johnny Brown (Presnell), bursts into song: “Colorado, My Home.” After happening upon Molly taking a bath in the river, he takes her to his cabin.

After a brief stay, she goes to Leadville and is hired by saloon owner Christmas Morgan (Jack Kruschen) as a singer and piano-player, though she cannot sing or play. Toying with the keyboard, Molly finds two notes, one in the treble, one in the bass, that comprise her “piano playing,” and she becomes a hit in “Belly Up to the Bar, Boys.”

After a brief stay, she goes to Leadville and is hired by saloon owner Christmas Morgan (Jack Kruschen) as a singer and piano-player, though she cannot sing or play. Toying with the keyboard, Molly finds two notes, one in the treble, one in the bass, that comprise her “piano playing,” and she becomes a hit in “Belly Up to the Bar, Boys.”

Johnny buys her some dresses and begins teaching her to read. Under a tree on a knoll, lessons continue and Presnell sings the key song of the musical, “I’ll Never Say No.” The song is the equivalent of “Till There Was You” in Willson’s first musical, The Music Man (1962). For tune detectives, “I’ll Never Say No” uncannily resembles the trio of the scherzo of Brahms’ Horn Trio in E-Flat.

Johnny remodels his cabin, with a room for Shamus and, for Molly, a bedroom with a big brass bed. The couple wed, but she confesses it isn’t what she wants, that there’s still . . . money. He sells his claim for $300,000, but unaware she has hidden it in the stove, he decides to warm himself after a cold bath, and—— No, money doesn’t matter after all, they decide. Johnny tosses a pickax in the air, it strikes a nearby mound of earth and gold trickles out.

Now back in the money, the Browns buy an enormous mansion in Denver, with a room for Seamus. They introduce themselves to the city’s social elite, crashing the party of Gladys McGraw (Audrey Christie), but they are excluded from the table of the so-called “Sacred 36” of Denver, and the butler closes the door in their faces.

Now back in the money, the Browns buy an enormous mansion in Denver, with a room for Seamus. They introduce themselves to the city’s social elite, crashing the party of Gladys McGraw (Audrey Christie), but they are excluded from the table of the so-called “Sacred 36” of Denver, and the butler closes the door in their faces.

An angry Molly then throws her own party. Nobody comes, though Shamus hits it off with “Buttercup” (Hermione Baddeley), Gladys’ mother. Molly decides the Browns will go to Europe and learn something about art, music and manners.

In Paris, they wander through museums, gaze at paintings, stare warily at nude statues and attend the opera. Molly takes piano and French lessons. The royalty like the down-to-earth Molly and she becomes the toast of Parisian society. At a clique fashion show, she meets the Grand Duchess Elise Lupavinova (Martita Hunt, Miss Havisham in Great Expectations [1947]), who winks at her, and becomes a friend.

In Paris, they wander through museums, gaze at paintings, stare warily at nude statues and attend the opera. Molly takes piano and French lessons. The royalty like the down-to-earth Molly and she becomes the toast of Parisian society. At a clique fashion show, she meets the Grand Duchess Elise Lupavinova (Martita Hunt, Miss Havisham in Great Expectations [1947]), who winks at her, and becomes a friend.

The couple return to Denver, accompanied by ten of Molly’s aristocratic friends. She intends to show the second-generation society of Denver some real culture. She does well at first. Mrs. McGraw is clearly impressed and shamed to be exposed as only a dilettante of the arts, unable to converse in French or German, paint or play the piano.

But things go awry when Johnny’s friends crash the party, resulting in a long rendition of “He’s My Friend.” Then a fight breaks out, and Molly’s plans for gaining the approval of Denver society are destroyed.

She returns to Europe—without Johnny, who tells her he’s saying “no” for the first time. Before long, she realizes that putting herself before others is wrong and sets sail for home on the Titanic. When the liner sinks, she rescues many of the passengers, giving up her fur coat.

She returns to Europe—without Johnny, who tells her he’s saying “no” for the first time. Before long, she realizes that putting herself before others is wrong and sets sail for home on the Titanic. When the liner sinks, she rescues many of the passengers, giving up her fur coat.

Returning home, now as a headlining heroine, she is accepted by all of Denver, including Mrs. McGraw, and, of course, Johnny.

Margaret, actually “Maggie,” Brown was a real person, born in Missouri and dying in 1932 at age 65, but much of The Unsinkable Molly Brown is far from accurate. Certain liberties are taken, both with the facts of the real Brown and with simple screen logic. It is a musical, after all, so these liberties are expected and can mostly be excused. If it goes on a little too long for the material at hand—the musical has far fewer and less memorable songs than The Music Man—and becomes sluggish at times, it is nevertheless high screen entertainment, typical of the decade, the era and the history of the American musical.

Debbie Reynolds is the star and she takes charge, no doubt about it. Her vitality and sincerity—and her likeability—compensate for the deficiencies in the film. It’s possible to see in her portrayal of Molly a reflection of Reynolds’ own character—determined, someone who knows what they want, a survivor. It’s possible, as well, to see in Molly’s distraught anguish, in that scene before her final departure from Paris, the shattering traumas in the actress’s own life—the scandalous lost of first husband, Eddie Fisher, to Elizabeth Taylor, the bankruptcy of her second husband and the death of daughter Carrie Fisher one day before she herself died of a stroke.

Debbie Reynolds is the star and she takes charge, no doubt about it. Her vitality and sincerity—and her likeability—compensate for the deficiencies in the film. It’s possible to see in her portrayal of Molly a reflection of Reynolds’ own character—determined, someone who knows what they want, a survivor. It’s possible, as well, to see in Molly’s distraught anguish, in that scene before her final departure from Paris, the shattering traumas in the actress’s own life—the scandalous lost of first husband, Eddie Fisher, to Elizabeth Taylor, the bankruptcy of her second husband and the death of daughter Carrie Fisher one day before she herself died of a stroke.

Perhaps, finally, Debbie Reynolds was what Molly Brown called “down,” what she never wanted to be. Perhaps it was more than the actress could take.