“With these indoor habits of yours, you’ve got the complexion of a gravel pit.”— Joseph to Professor Lightcap

“With these indoor habits of yours, you’ve got the complexion of a gravel pit.”— Joseph to Professor Lightcap

Jean Arthur comes to The Talk of the Town with more than simply good recommendations and experience in the genre of comedy. The sparkle-faced actress with the squeaky, frog-like voice and a persona of immediate likeability is a master of comedy; even mad, she is charming. Before 1942, she had appeared in such comic/social-minded comedies as Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, You Can’t Take It with You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and The Devil and Mrs. Jones. Frank Capra, the spokesman for the common man par excellence, directed all of them except Sam Wood in the last.

For The Talk of the Town, Arthur would have still another director, George Stevens, who would guide her in two subsequent films, The More the Merrier (1943), reuniting her with co-star Joel McCrea, andShane (1953), her final film before retiring from the screen.

During her career, Jean Arthur made a remarkably high percentage of excellent films, many of them four-star, a more impressive achievement than most of her contemporary actresses. She was wise enough—or frightened enough—to retire while she was on top. “Frightened” because she was plagued by a severe, and constant, case of stage fright—famous for it and notorious for the poor directors who didn’t know how to handle her.

Frank Capra, who had directed her in only one film prior to Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), vividly describes his experience with her on that film and, at the same time, touches upon a part of her special screen magic: “You can’t get her out of the dressing room without using force. You can’t get her in front of the camera without her crying, whining, vomiting, all that [stuff] she does. But then, when she does get in front of the camera, and you turn on the lights—wow! All of that disappears and out comes a strong-minded woman. Then when she finishes the scene, she runs back to the dressing room and hides.”

Frank Capra, who had directed her in only one film prior to Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), vividly describes his experience with her on that film and, at the same time, touches upon a part of her special screen magic: “You can’t get her out of the dressing room without using force. You can’t get her in front of the camera without her crying, whining, vomiting, all that [stuff] she does. But then, when she does get in front of the camera, and you turn on the lights—wow! All of that disappears and out comes a strong-minded woman. Then when she finishes the scene, she runs back to the dressing room and hides.”

Cary Grant plays himself pretty much, though the debonair lover, the master of charisma, is toned down a bit, and not once does he appear in evening clothes. After all, he’s supposed to be a labor activist—how colorful is that, something of a downbeat, uncomic theme for a film. Successful or interesting labor-themed films are rare—On the Waterfront (1954) being one of the few, and even then, it is hard going sometimes. Rest assured, The Talk of the Town is not remotely a labor film.

In competition with Grant for the affections of Arthur is another master of the debonair, though in a quieter, more subtle way. Not a man of physical action or overt romancing, and in a role he assumes often, Ronald Colman is the intellectual—in this case a law professor—who prefers reading, playing chess, lounging about in his smoking jacket and taking his tea at the proper times.

In competition with Grant for the affections of Arthur is another master of the debonair, though in a quieter, more subtle way. Not a man of physical action or overt romancing, and in a role he assumes often, Ronald Colman is the intellectual—in this case a law professor—who prefers reading, playing chess, lounging about in his smoking jacket and taking his tea at the proper times.

During most of the movie Arthur’s character plays it down the middle between the two men, and not until the very end and only after a plot hesitation is her choice made in a suspenseful twist. Some viewers are disappointed that she didn’t pick “the other one.”

The first of the two most obvious negatives in The Talk of the Town is Grant’s too-frequent sermonizing. His speeches, certainly in their individual length and frequency, violate the spirit of this romantic comedy—and it’s bit of a mystery, too, because Grant’s guilt as an alleged criminal is unclear most of the time.

The film’s second negative is the lackluster performance by some of the supporting players. In 1942, many of the familiar faces were away in the war, and, as well, Columbia Pictures never had as impressive a roster of supporting players as did Warner Bros. or M-G-M. The studios were borrowing players from one another to meet their casting needs.

The credited actors are impressive enough—Edgar Buchanan, Glenda Farrell, Charles Dingle, Tom Tyler, Don Deddoe and Rex Ingram, refreshingly not cast as the stereotypical black man, so prevalent at the time. Rather it’s many of the uncredited actors who leave something to be desired. Lloyd Bridges, the most recognizable face among them, and who actually is given a screen name, is a little stiff and seemingly out of place in his too “dressed up” attire in his one scene.

The credited actors are impressive enough—Edgar Buchanan, Glenda Farrell, Charles Dingle, Tom Tyler, Don Deddoe and Rex Ingram, refreshingly not cast as the stereotypical black man, so prevalent at the time. Rather it’s many of the uncredited actors who leave something to be desired. Lloyd Bridges, the most recognizable face among them, and who actually is given a screen name, is a little stiff and seemingly out of place in his too “dressed up” attire in his one scene.

Cary Grant a criminal?! Seems so. In prison for setting fire to a mill and causing a foreman’s death, he chokes, presumably to death, a guard and escapes. Since high school political activist Leopold Dilg (Grant) had been attracted to Nora Shelley (Arthur), so, naturally, he takes refuge in her nearby cottage, Sweetbrook.

Now a schoolteacher, though nothing supports that in the film, Nora is renting the cottage to a renowned law professor Michael Lightcap (Colman), who is scheduled to arrive the next day. But he arrives a day early, in a rainstorm. She keeps him waiting, in the rain, while she helps Dilg hide in the attic. He has sprained an ankle during his escape.

Now a schoolteacher, though nothing supports that in the film, Nora is renting the cottage to a renowned law professor Michael Lightcap (Colman), who is scheduled to arrive the next day. But he arrives a day early, in a rainstorm. She keeps him waiting, in the rain, while she helps Dilg hide in the attic. He has sprained an ankle during his escape.

On the pretense that she can’t go home, that she and her mother are quarreling at the moment, she persuades the bearded, aristocratic Lightcap to let her stay overnight, even borrowing a pair of his pajamas. During the night, trying to sleep, Lightcap overhears Dilg’s snoring in an adjacent room and complains politely next morning that Nora must have adenoids. At first caught off guard, she quickly recovers, saying that, yes, they’re as big as fists.

Next morning the peace of Sweetbrook, where Lightcap has come to write a law tome in the quiet of the country, is abruptly broken by what Dilg, observing from his hiding place upstairs, calls a regular parade. First Nora’s mother (Emma Dunn) arrives, hardly seeming at odds with her daughter, which Nora explains to Lightcap—she’s “very changeable.” Close behind, reporter Donald Forrester (Bridges) barges in to interview the famous law professor, and furniture movers drop in with a set of upholstered chairs. Now Lightcap’s annoyance grows even higher.

A welcomed sight, however, is old friend Sam Yates (Buchanan), who updates him on, and stands up for, this Leopold Dilg, a name unfamiliar to Lightcap. “He’s the only honest man I’ve come across in this town in twenty years,” Yates says. “Naturally, they want to hang him.” Lightcap announces that he’s only interested in academic law, not in handling local criminal problems.

A welcomed sight, however, is old friend Sam Yates (Buchanan), who updates him on, and stands up for, this Leopold Dilg, a name unfamiliar to Lightcap. “He’s the only honest man I’ve come across in this town in twenty years,” Yates says. “Naturally, they want to hang him.” Lightcap announces that he’s only interested in academic law, not in handling local criminal problems.

Before Yates leaves, Nora tells him privately that she’s hiding Dilg in her attic, that Yates must get him out. He counters that Dilg is safest where he is, where she can take care of him.

Lightcap asks Nora if she knows of any reliable woman in town, that he needs a cook and a stenographer. Because she needs to be around to guard and care for Dilg, Nora volunteers for the job, suggesting he needs quiet with no people trampling about. “Judging by the last twelve hours,” Lightcap responds, “how quiet could the house be with you in it?” After much hesitation, he accepts the persuasive Nora.

At that moment the Western Union boy (William Benedict) arrives on a backfiring motorbike. Lightcap receives a wire from “his man” Tilney (Ingram), who remembered that day was the professor’s birthday.

At that moment the Western Union boy (William Benedict) arrives on a backfiring motorbike. Lightcap receives a wire from “his man” Tilney (Ingram), who remembered that day was the professor’s birthday.

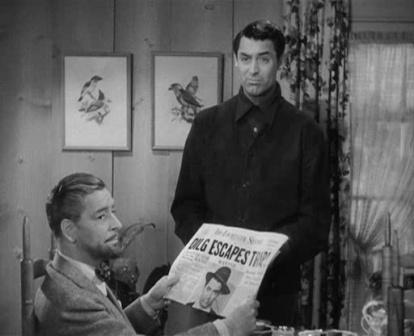

While raiding the refrigerator for something to eat, Dilg overhears from the patio Lightcap’s dictation to Nora and steps outside to disagree with what he’s heard. Nora quickly introduces him as Joseph the gardener. The two men soon began to exchange ideas about the law, often the inequality of it, Joseph a proponent of its practical application, Lightcap maintaining his more academic stance.

The next visitor to Sweetbrook is Senator James Boyd (Clyde Fillmore), who has come to offer Lightcap a bench on the U.S. Supreme Court, a request by the President. After only a moment’s hesitation, Lightcap accepts.

The plot is unusually sophisticated and complicated for a comedy, too detailed for adequate inclusion here. There are many other episodes, including the arrival of Lightcap’s valet Tilney, a visit to a baseball game and a riot instigated by the mill owner (Dingle). Joseph, then Lightcap, are chased by a pack of police bloodhounds; Lightcap inadvertently wears Joseph’s discarded slippers which give the dogs Joseph’s scent.

The plot is unusually sophisticated and complicated for a comedy, too detailed for adequate inclusion here. There are many other episodes, including the arrival of Lightcap’s valet Tilney, a visit to a baseball game and a riot instigated by the mill owner (Dingle). Joseph, then Lightcap, are chased by a pack of police bloodhounds; Lightcap inadvertently wears Joseph’s discarded slippers which give the dogs Joseph’s scent.

Knowing Joseph’s fondness for borscht, and having grown to like and admire the gardener, Lightcap, while downtown, orders a quart of the soup from a shop. At a special dinner that night, with the once rather stuffy professor now enjoying the company of both Joseph and Nora and settled into the crazy routine of Sweetbrook cottage, he presents his surprise. Removing the newspaper the shop’s proprietor (Leonid Kinskey) used to wrap the borscht, he sees a headline with Joseph’s, er, Leopold Dilg’s picture.

Lightcap attempts to phone the police. Dilg knocks him out and flees. Lightcap visits Sam Yates for counsel and asks him to work for Dilg’s vindication. Yates shows Lightcap a fire inspection certificate signed by Clyde Bracken (Tom Tyler), the man supposedly killed in the fire, and he suspects something isn’t right.

Lightcap attempts to phone the police. Dilg knocks him out and flees. Lightcap visits Sam Yates for counsel and asks him to work for Dilg’s vindication. Yates shows Lightcap a fire inspection certificate signed by Clyde Bracken (Tom Tyler), the man supposedly killed in the fire, and he suspects something isn’t right.

Having shaved off his beard, symbolizing the change in his character and provoking tears from Tilney, Lightcap believes the way to prove Dilg’s innocence lies in Regina Bush (Glenda Farrell), the girlfriend of Bracken. He takes her dancing and to a restaurant. While his wooing is sometimes clumsy—“your physical coordinations are remarkable”—the naïve woman is flattered and in an unguarded moment shows him an envelope. The return address displays Bracken’s name, and she admits he is living inBoston.

Summarizing some of the plot details, Nora finds Dilg hiding in Sweetbrook cottage, Lightcap apprehends Bracken at a post office in Boston, Bracken admits the mill fire was set by the owner for the insurance and Dilg is finally captured by the police.

Lightcap crashes Dilg’s trial, fires a gun—the sedate professor has changed!—and produces Bracken. Dilg is exonerated (his killing of the prison guard is apparently overlooked) and Lightcap gives a stirring address to the court, strangely reflecting some of Dilg’s ideas: “ . . . the law has got to be the personal concern of every citizen. It can’t exist unless we’re willing to go down into the dust and blood and fight a battle every day of our lives to preserve it.”

Lightcap crashes Dilg’s trial, fires a gun—the sedate professor has changed!—and produces Bracken. Dilg is exonerated (his killing of the prison guard is apparently overlooked) and Lightcap gives a stirring address to the court, strangely reflecting some of Dilg’s ideas: “ . . . the law has got to be the personal concern of every citizen. It can’t exist unless we’re willing to go down into the dust and blood and fight a battle every day of our lives to preserve it.”

Before making his first appearance in the opening session of the Supreme Court, Lightcap movingly confesses to Nora his affections but suggests she marry Dilg. Both Nora and Dilg are in the audience at the session, and when she winks at Lightcap, Dilg assumes she is in love with the judge and leaves. Nora follows him. Now it’s Dilg who offers romantic advice, that she marry Lightcap. After some ambiguous, back-and-forth dialogue, he finally walks away. She runs after him and kisses him, and they walk off camera together.

Not always a reliable indication but in this case most of the seven Oscar nominations in 1942 for The Talk of the Town are largely justified. None of the seven yield fruit, however.

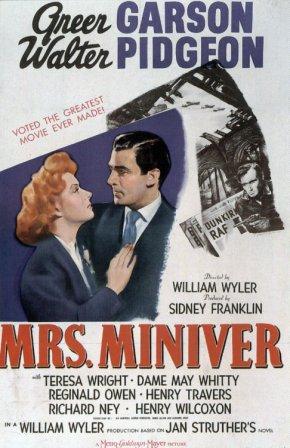

From the top, Best Picture goes to Mrs. Miniver, not surprising—a morale booster for the U.S., which had entered World War II nine months before The Talk of the Town was released. In the context of the devastating war news, a comedy seems a little out of place, especially among the heavier, more relevant nominees, 49th Parallel, Wake Island and Mrs. Miniver.

From the top, Best Picture goes to Mrs. Miniver, not surprising—a morale booster for the U.S., which had entered World War II nine months before The Talk of the Town was released. In the context of the devastating war news, a comedy seems a little out of place, especially among the heavier, more relevant nominees, 49th Parallel, Wake Island and Mrs. Miniver.

Although the Cary Grant film is unrepresented in the Best Actor category, Ronald Colman is nominated for Random Harvest, also war-related, if another war. The winner is James Cagney, also from another patriotic morale booster, Yankee Doodle Dandy—a flag-waver if ever there was one—with a silhouetted FDR in the final scene.

Surprisingly, George Stevens is denied a Best Director nod; the Oscar goes to William Wyler for Mrs. Miniver.

The Talk of the Town is nominated in two of the then three writing categories, Adapted Screenplay and Original Story, the latter to be dropped after 1956 (the third category is Original Screenplay). Two of the three winners are war related.

The 1942 Oscar nominees for Black and White Cinematography include some of the greatest names in the profession—James Wong Howe, Joseph Ruttenberg, Arthur Miller, Stanley Cortez, Edward Cronjager, Rudolph Maté and Leon Shamroy, with 44 nominations and 13 wins among them. If a notch or two below most of these illustrious gentlemen, Talk of the Town cinematographer Ted Tetzlaff, who shot My Man Godfrey (1936) and Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), loses to Ruttenberg for Mrs. Miniver.

In contrast with the cinematographers, despite the eighteen nominees for Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture (the extravagant number common in some pre-1946 years), 1942 is a weak year for background music. The join effort of Frederick Hollander and Morris Stoloff for The Talk of the Town, one of the year’s best, supports well the film’s comic-romantic-mystery-dramatic mixture, but is helpless against the onslaught of Max Steiner’s schmaltzy, syrupy Now, Voyager.

In contrast with the cinematographers, despite the eighteen nominees for Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture (the extravagant number common in some pre-1946 years), 1942 is a weak year for background music. The join effort of Frederick Hollander and Morris Stoloff for The Talk of the Town, one of the year’s best, supports well the film’s comic-romantic-mystery-dramatic mixture, but is helpless against the onslaught of Max Steiner’s schmaltzy, syrupy Now, Voyager.

No criticism of Steiner—he is in his element and does Bette Davis’ hand-wringing proud—but Alfred Newman’s The Black Swan is ground-breaking and more original. Surely, though, the best score of 1942 is the one elephant not in the room when nominations were passed out: Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Kings Row, an embarrassing omission.

The two remaining unsuccessful nominees for The Talk of the Town are for Editing and Black and White Interior Decoration.