“No law west of Chicago . . . west of Dodge City no god.” — Dr. Irving (Henry Travers)

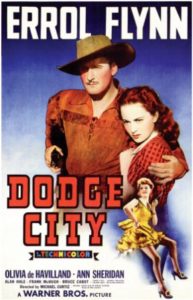

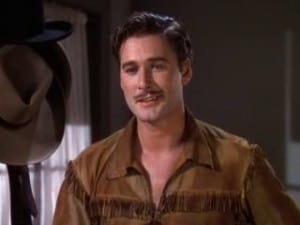

Although not much outside of women and drink, perhaps sailing, seriously interested Errol Flynn, he was possibly a little concerned about how his English/Irish/Australian accent—take your pick—would be accepted in Dodge City, his first American Western.

Warner Bros. was a bit more concerned. True, Errol had fit cozily, and totally convincingly, into the English ambiance of Captain Blood, The Charge of the Light Brigade, The Prince and the Paper, The Adventures of Robin Hood and Dawn Patrol—fit, in fact, into most of his first eleven films, tailored as they were to his cultured manner and well-spoken English. But how would this persona be accepted in the character of an American cowboy, who, in the mid-nineteenth century, would be half-educated at most and more than just a little rough around the edges?

To justify the admitted incongruity of his accent, rather early in the Dodge City script, inserted into the dialogue of an old friend, the character of Colonel Dodge (Henry O’Neill), is the explanation of this Irishman atop a horse in the American West of 1866. He had been, it seems, in India with the British Army, had fought in a “revolution” in Cuba (though, historically, there was no official revolution until 1868-1898), been in “Jeb” Stuart’s rebel cavalry during the just-ended Civil War and, now, was a cattleman in Texas.

Even Flynn’s character alludes to his past, in a humorous moment when he trips over a bundle of tax forms and falls on the floor of the newspaper office in front of his lovely co-star: “There’s a saying in the British army: ‘The law must always save its face in front of the natives.’ ” And after the laughing young lady wonders if he’s suggesting she’s a native, he explains that the only true native of Kansas is the buffalo.

After Dodge City, Errol Flynn’s Irish background was never mentioned again in any of his seven subsequent Westerns. As time passed, by the way, these Westerns, except for the next one, Virginia City, showed a gradual decline in quality, production value and watchability, all the way through to 1950 and Rocky Mountain and—no pun intended—“rock” bottom. The big exception, coming four years after Dodge City, is They Died with Their Boots On, the best Western Flynn made—and his first movie with director Raoul Walsh.

Whatever the failings of Dodge City—a generally poor script, cardboard characters, a simplistic depiction of good versus evil and a trunk full of Western clichés—its pluses include Flynn’s never-failing charm, at least at this point in his career before drinking and drugs took their toll; three-strip Technicolor, warmly photographed, with a subtle burnt sienna tone, by Sol Polito; the lovely Olivia de Havilland, in her fifth Flynn vehicle; and some rip-roaring action, highlighted by a standard-setting saloon brawl.

Whatever the failings of Dodge City—a generally poor script, cardboard characters, a simplistic depiction of good versus evil and a trunk full of Western clichés—its pluses include Flynn’s never-failing charm, at least at this point in his career before drinking and drugs took their toll; three-strip Technicolor, warmly photographed, with a subtle burnt sienna tone, by Sol Polito; the lovely Olivia de Havilland, in her fifth Flynn vehicle; and some rip-roaring action, highlighted by a standard-setting saloon brawl.

This saloon slugfest has all the ingredients of such a fracas: falls from balconies, crashes through plate-glass windows, chairs and tables thrown, several men falling through a staircase (the highlight of the romp maybe), a pulling down of the bar mirror and a melee of several dozen men slugging away at one another. This would set a standard for all future Westerns. Watching it now, though it’s been clichéd and satirized to death, it’s all very exhilarating, hard to resist, as it must have been, even more so, in 1939.

A cattle stampede, a corrupt town in need of taming, a stagecoach-train race, men leaping on horses from the moving train, an evil town tyrant, a mob assault on a jail, a near-hanging, the rescue of the heroine by the hero from a train baggage car fire—what isn’t already a cliché in the film, if there is anything, would eventually become so in movies to come. But it is all handled by director Michael Curtiz with sweep and style, including his shadows-on-the-wall trademark, the well-staged action sequences and the use of as many extras and “stand arounds” as possible to fill the screen, as backdrops for the foreground action.

A cattle stampede, a corrupt town in need of taming, a stagecoach-train race, men leaping on horses from the moving train, an evil town tyrant, a mob assault on a jail, a near-hanging, the rescue of the heroine by the hero from a train baggage car fire—what isn’t already a cliché in the film, if there is anything, would eventually become so in movies to come. But it is all handled by director Michael Curtiz with sweep and style, including his shadows-on-the-wall trademark, the well-staged action sequences and the use of as many extras and “stand arounds” as possible to fill the screen, as backdrops for the foreground action.

Curtiz was a hard taskmaster, both on actors and crews, and he expected everyone to work at his frantic pace and with his determination. Flynn and Curtiz would make twelve films together, including many of the actor’s best. After Dive Bomber, with the prevalence of dialogue over action and plot-dragging technical talk, the two mutually agreed to part ways, and Flynn would turn to Walsh for his next film, Boots, and a good many thereafter.

Besides Flynn as the transplanted soldier of fortune Wade Hatton and de Havilland as Abbie Irving, the cast is well represented with some of Warners’ familiar faces. Third-billed Ann Sheridan, in an unfortunately small part, is saloon dancer Ruby. The star, oddly neglected by the studio at the beginning of her career, would shine in two quite different films in the next two years, the serious, even gloomy Kings Row and the hilarious comedy The Man Who Came to Dinner. In Dodge City, she sings “Little Brown Jug” and “I’se Gwine Back to Dixie” with charm and sparkle.

Besides Flynn as the transplanted soldier of fortune Wade Hatton and de Havilland as Abbie Irving, the cast is well represented with some of Warners’ familiar faces. Third-billed Ann Sheridan, in an unfortunately small part, is saloon dancer Ruby. The star, oddly neglected by the studio at the beginning of her career, would shine in two quite different films in the next two years, the serious, even gloomy Kings Row and the hilarious comedy The Man Who Came to Dinner. In Dodge City, she sings “Little Brown Jug” and “I’se Gwine Back to Dixie” with charm and sparkle.

When Ruby and the girls sing “Marching Through Georgia” and some saloon patrons join in, the cowhands from Flynn’s cattle drive sing back with “Dixie.” (The girls’ blue and pink dresses are almost too resplendent in Technicolor, but eye-catching nonetheless.) Generally unnoticed here, a few years later a similar choral duo would become one of the highlights of Casablanca, with a vocal contest between “La Marseillaise” and “Die Wacht am Rhein.”

An ideal among arch-villains, Bruce Cabot as Jeff Surrett, the despot of Dodge City, is truly despicable, with a low-key, smoldering brand of cynicism, who has one henchman, Yancey (Victor Jory), do his dirty work. Yancey kills a number of the supporting players, among them Matt Cole (John Litel), whose only crime was trying to collect his rightful money for the cattle he had sold to Surrett, and the newspaper editor Joe Clemens (Frank McHugh), whose simply wanted to print the truth and campaign against corruption in Dodge City.

An ideal among arch-villains, Bruce Cabot as Jeff Surrett, the despot of Dodge City, is truly despicable, with a low-key, smoldering brand of cynicism, who has one henchman, Yancey (Victor Jory), do his dirty work. Yancey kills a number of the supporting players, among them Matt Cole (John Litel), whose only crime was trying to collect his rightful money for the cattle he had sold to Surrett, and the newspaper editor Joe Clemens (Frank McHugh), whose simply wanted to print the truth and campaign against corruption in Dodge City.

Cabot was a drinking buddy of Flynn’s and would later fill a similar role for John Wayne, who included him in many of his movies when Cabot was past his useful prime.

Henry Travers, best known as Clarence the angel second class who comes to Earth in It’s A Wonderful Life to show James Stewart the importance of his life, plays Dr. Irving, an amiable father to both Abbie and Lee (William Lundigan). When an intoxicated Lee fires his gun for fun, Hatton warns him he might stampede the cattle. Lee draws his weapon, Hatton, in self-defense, shoots him in the leg. The gunfire stampedes the cattle and Lee is trampled to death.

Dr. Irving offers the vacant job of sheriff to Hatton, but Hatton turns it down—until a young boy, Harry Cole (Bobs Watson), who had innocently tethered horses for a few cents and played cowboy with his wooden gun, is dragged to his death by run-away horses, broken loose from a buckboard. The animals were frightened by gunfire from a street shootout, only one sign of Dodge City’s lawlessness—and, yes, its need of a sheriff. Harry’s mother (Gloria Holden) plans to leave town after her husband’s, then her son’s, death.

Clem Bevans is a nervous barber about to trim Hatton’s mustache after Hatton has thrown another Surrett henchman (Douglas Fowley) out on the street. Still another Surrett cohort is played by the ever-present Ward Bond—he made over 250 films in thirty years—who, as Bud Taylor, is finally persuaded to admit that Yancey was absent from the saloon when Clemens was killed in his office. (A clue linking Yancey to the crime is the printer’s ink on his hand from Clemens’ safe.)

Clem Bevans is a nervous barber about to trim Hatton’s mustache after Hatton has thrown another Surrett henchman (Douglas Fowley) out on the street. Still another Surrett cohort is played by the ever-present Ward Bond—he made over 250 films in thirty years—who, as Bud Taylor, is finally persuaded to admit that Yancey was absent from the saloon when Clemens was killed in his office. (A clue linking Yancey to the crime is the printer’s ink on his hand from Clemens’ safe.)

Perhaps even overshadowing at times the Flynn-de Havilland pairing, the real attention-grabbers are Hatton’s two sidekicks—Tex played by Guinn (“Big Boy”) Williams and Rusty by Alan Hale, Flynn’s forever-favorite screen buddy. Hale appears in twelve Flynn movies, beginning with The Prince and the Pauper (as an enemy) and most famously as Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood. Some of his more prominent parts occur in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (again as an adversary), The Sea Hawk, Desperate Journey and Gentleman Jim. The best supporting performance in Gentleman Jim, however, is Ward Bond’s moving portrayal of boxer John L. Sullivan, who, in the humblest of tones, presents the championship belt to Jim Corbett (Flynn) after Corbett has defeated him in the ring.

Flynn and Hale’s last film together would be Adventures of Don Juan (1948), something of a satire on the actor’s own amorous adventures, on and off the screen. Irresistible in quoting here, so forgive the digression, is one of the best lines in a movie full of sharp repartee and romances gone wrong. On one of several occasions, Don Juan (Flynn) is in prison, along with his Sancho Panza of sorts, Leporello (Hale). Juan is bemoaning having forgotten a previous ship in the night (Helen Westcott). “Oh, there must be something in life more important than the pursuit of women,” Leporello muses. And Juan replies pensively, “Yes—there must be . . . but what?”

Flynn and Hale’s last film together would be Adventures of Don Juan (1948), something of a satire on the actor’s own amorous adventures, on and off the screen. Irresistible in quoting here, so forgive the digression, is one of the best lines in a movie full of sharp repartee and romances gone wrong. On one of several occasions, Don Juan (Flynn) is in prison, along with his Sancho Panza of sorts, Leporello (Hale). Juan is bemoaning having forgotten a previous ship in the night (Helen Westcott). “Oh, there must be something in life more important than the pursuit of women,” Leporello muses. And Juan replies pensively, “Yes—there must be . . . but what?”

As for Dodge City, Hale’s big moment is a visit to a temperance meeting of a group of elderly women, eager to welcome the only man to the Pure Prairie League. As Rusty is stumbling and fumbling in a testimonial on the evils of drink and his past life—“I was brung up by Comanche Indians”—the noise from the brawl in the saloon next door distracts—and tempts—him. Finally, when some of the participants in the fight come crashing through the wall, what could he do but join in?

Tex, having been put in jail for carrying a gun in the city, is released, saying he wants to move on, complete with his hobo-like belongings tied to a stick over his shoulder. Wade and Rusty try to convince him to stay, then make their good-byes and, finally, Hatton says, “Give him back his gun, Rusty.” Tex takes the gun and starts to leave the sheriff’s office. “Arrest that man, Rusty!” Hatton says, and reminds him that he’s carrying a gun within the city limits!

Tex, having been put in jail for carrying a gun in the city, is released, saying he wants to move on, complete with his hobo-like belongings tied to a stick over his shoulder. Wade and Rusty try to convince him to stay, then make their good-byes and, finally, Hatton says, “Give him back his gun, Rusty.” Tex takes the gun and starts to leave the sheriff’s office. “Arrest that man, Rusty!” Hatton says, and reminds him that he’s carrying a gun within the city limits!

Best of all are Flynn and de Havilland, like magic together, though much of the time in Dodge City she wears a detracting amount of rouge. The duo is, after all, the reason the film was made in the first place, in response to the public’s clamoring for them, especially after Robin Hood. Flynn’s three films between Robin Hood and Dodge City, however, were far from what the fans wanted. In the first, Four’s A Crowd, their ardor is a little tepid, and somehow dulled by the modern setting, their first. In The Sisters, the actor is given a different love interest (Bette Davis) and, worse, cast atypically as a weakling. In the third, The Dawn Patrol, Flynn is back in his element as British, now as a fighter pilot during World War I, but the cast is, oops, all-male.

Although Flynn is always ready and eager to move forward, as it were, in any of his film romances with de Havilland, the scripts often call for subtle differences in her reception of him. In The Charge of the Light Brigade, for example, she discourteously falls in love with someone else (Patric Knowles). In Elizabeth and Essex she is essentially ignored, so blinded is Flynn’s character by his lust for power that he prefers to pursue that power’s source, the queen (Davis). These, though, are the extremes in the pair’s relationship on screen, short of his being killed—in both these films, as well as They Died with Their Boots On, the couple’s last pairing.

Although Flynn is always ready and eager to move forward, as it were, in any of his film romances with de Havilland, the scripts often call for subtle differences in her reception of him. In The Charge of the Light Brigade, for example, she discourteously falls in love with someone else (Patric Knowles). In Elizabeth and Essex she is essentially ignored, so blinded is Flynn’s character by his lust for power that he prefers to pursue that power’s source, the queen (Davis). These, though, are the extremes in the pair’s relationship on screen, short of his being killed—in both these films, as well as They Died with Their Boots On, the couple’s last pairing.

One frequent wooing course, with certain subtle variations, represented in, say, Captain Blood and Robin Hood, is adopted for Dodge City. That is, first, a subtle attraction, as when Abbie allows Wade to carry a bucket of water for her; then sudden disdain after her brother’s death, even though it isn’t his fault; followed by an almost abrupt lessening of her resistance, implied in the scene in the newspaper office and his confiding to her the ink smudge on her nose; and, finally, total capitulation—the prairie scene on a hill, under an oak tree, and their first kiss.

(The Captain Blood courting progression, by the way, is very subtle, perhaps the most nuanced and sophisticated in the Flynn-de Havilland films. For one thing, when she is initially attracted to him, teases him and even laughs—“I’m just thinking how annoyed Peter Blood would be if I did him another favor!”—he is actually resentful of her attention . . . and so on. An adequate study of this romance is both inappropriate here and beyond these pages.)

As a preface to that first kiss in Dodge City, the two riders dismount and sit on the ground, Hatton playing with a twig of grass. “We had such a bad beginning,” he says, “we’re bound for a wonderful future.” He proceeds to tell Abbie how badly his parents’ life together began. They met at the Londonderry Fair, he relates. (More support for Hatton’s Irish background.) His father had brought his pigs and his mother her roses—“ . . . enormous, big things as big as your face and nearly as beautiful.” Well, his father’s pigs escape and eat all of his mother’s roses. “Did any two people ever get off to a worse start than that? Look at them now—six big, lusty sons, a score of prize pigs and the most beautiful rose garden in the whole of Antrim.”

As a preface to that first kiss in Dodge City, the two riders dismount and sit on the ground, Hatton playing with a twig of grass. “We had such a bad beginning,” he says, “we’re bound for a wonderful future.” He proceeds to tell Abbie how badly his parents’ life together began. They met at the Londonderry Fair, he relates. (More support for Hatton’s Irish background.) His father had brought his pigs and his mother her roses—“ . . . enormous, big things as big as your face and nearly as beautiful.” Well, his father’s pigs escape and eat all of his mother’s roses. “Did any two people ever get off to a worse start than that? Look at them now—six big, lusty sons, a score of prize pigs and the most beautiful rose garden in the whole of Antrim.”

In this scene, aside from the panorama of the prairie and the buffalo “grazing away so peacefully,” as Hatton says, underpinning it all is Max Steiner’s score, here concentrating on Abbie’s theme.

Dimitri Tiomkin is always credited as the master of the Western score, and rightfully so, but it’s often forgotten that Steiner wrote a few outstanding ones in this genre as well, Dodge City being one of his finest. The main title opens with the grand empire-building theme, symbolizing the westward expansion of America and its Manifest Destiny declaration, more accurately its imperialism. After the stagecoach-train race in the film’s beginning, “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” is played by a band as the train pulls into Dodge City.

Dimitri Tiomkin is always credited as the master of the Western score, and rightfully so, but it’s often forgotten that Steiner wrote a few outstanding ones in this genre as well, Dodge City being one of his finest. The main title opens with the grand empire-building theme, symbolizing the westward expansion of America and its Manifest Destiny declaration, more accurately its imperialism. After the stagecoach-train race in the film’s beginning, “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” is played by a band as the train pulls into Dodge City.

Steiner’s score reflects now the drama, now the humor, now the action, for the switch on screen is often kaleidoscopic. The easy melody and strumming guitars for the vistas of cattle on the wide prairie recall in a later film, Red River, some of Tiomkin’s intuitive sweep and Russell Hardan’s expansive cinematography. There’re frantic, hell-bent-for-leather rhythms to accompany galloping horses and racing locomotives. Nothing is ponderous, the scoring seems unusually light and fresh for Steiner. He never loses the lyrical touch—he was, after all, Viennese—often creating folk-like tunes. For a change, the composer largely represses his penchant for inserting into his music at every opportunity popular or traditional tunes. Except for “Oh! Susanna,” played during a cattle drive, most of the familiar tunes are heard as source music.

Dodge City ends in a hotel room. Colonel Dodge is talking to Hatton and his two sidekicks. There’s another lawless town, the colonel says, Virginia City, that needs taming—one that needs a man like Hatton. Rusty and Tex are excited, ready to go. Reluctantly, Hatton rejects any such idea. Abbie, having stood in the next room and overheard through a crack in the door, enters with lemonade for everyone. Hatton, clearly forcing his enthusiasm, says he was just telling Dodge about their honeymoon in New York, “How we’ll see all the shops, the theaters and Niagara Falls and . . . things.” Abbie says, “Colonel Dodge, when do we start for Virginia City?” Yes—total capitulation for the man she loves.

Dodge City ends in a hotel room. Colonel Dodge is talking to Hatton and his two sidekicks. There’s another lawless town, the colonel says, Virginia City, that needs taming—one that needs a man like Hatton. Rusty and Tex are excited, ready to go. Reluctantly, Hatton rejects any such idea. Abbie, having stood in the next room and overheard through a crack in the door, enters with lemonade for everyone. Hatton, clearly forcing his enthusiasm, says he was just telling Dodge about their honeymoon in New York, “How we’ll see all the shops, the theaters and Niagara Falls and . . . things.” Abbie says, “Colonel Dodge, when do we start for Virginia City?” Yes—total capitulation for the man she loves.

Virginia City would, indeed, be Errol Flynn’s next Western, following that little appointment with the axe in Elizabeth and Essex. Not a sequel to Dodge City, the film is set during instead of after the Civil War. Back would be Michael Curtiz, Max Steiner, cinematographer Polito and Alan Hale and Guinn Williams, as well as a number of the supporting cast, including McHugh, Bond and Litel. But not back was Technicolor—or Olivia. Flynn would be saddled, if maybe too harsh a reproach, with a different leading lady, one less graceful, less charming, less worthy of Flynn’s attentions—Miriam Hopkins. Olivia would be, and is, solely missed in Virginia City.