“India forces one to come face to face with oneself.”——Peggy Ashcroft as Mrs. Moore

One of producer Richard Goodwin’s Hollywood encounters illustrates the frequent confusion between the two writers E. M. Forster and C. S. Forester. When Goodwin was looking for an American backer for David Lean’s proposed next movie, A Passage to India, and the subject of the novel, British rule in post-World World I India, came up, the studio executive remarked, “Oh, I thought he only wrote Hornblower books.”

While sparing the executive embarrassment with an anonymous reference, Goodwin, at the same time, was providing yet another illustration of the naiveté of some of those Hollywood people. This recalls another executive—I’ve forgotten the film involved, perhaps Mahler or Death in Venice—who liked this fellow Gustav Mahler’s music in the score and urged that the studio sign him. Mahler had been dead since 1911.

No, no! The series of novels about Captain Horatio Hornblower, a hero of the Napoleonic Wars, was the fictional creation of C. S. Forester, with the extra “e.” He also penned The African Queen, which director John Huston turned into a masterpiece with Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart.

E. M. Forster, quite a different chap, who lived longer than his fellow Brit by a quarter century and was the more scholarly, is renowned for Howard’s End and A Room with a View. These are novels of social consciousness and about class prejudice, as is his most successful novel, A Passage to India of 1924. Forster had taken his title from a Walt Whitman poem, one of many that comprise a collection of poems written and published over the poet’s lifetime as part of his Leaves of Grass. For the remaining forty-six years of Forster’s long life he never wrote another novel.

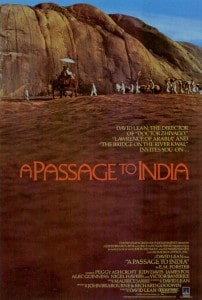

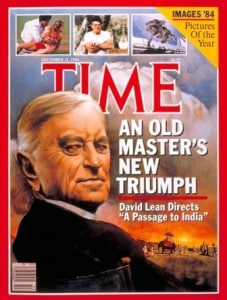

Much like David Lean who never made another film after A Passage to India in 1984, though he lived seven more years. After three triumphs in a row—The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago—he was devastated by the poor reception of his next film, the ponderous and misguided Ryan’s Daughter, and fourteen years would pass before he regained enough confidence to tackle the difficult A Passage to India. It was difficult because of logistics—all equipment and material, even Indian tea, had to be imported to India—and all sets had to be built in general isolation due to the uncontrollable crowds on actual Indian streets and at real temples.

Much like David Lean who never made another film after A Passage to India in 1984, though he lived seven more years. After three triumphs in a row—The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago—he was devastated by the poor reception of his next film, the ponderous and misguided Ryan’s Daughter, and fourteen years would pass before he regained enough confidence to tackle the difficult A Passage to India. It was difficult because of logistics—all equipment and material, even Indian tea, had to be imported to India—and all sets had to be built in general isolation due to the uncontrollable crowds on actual Indian streets and at real temples.

Alfred Hitchcock, like John Ford to a degree, and like most directors, had his special cameraman, editor and composer. So, for this new picture, Lean gathered around him his favorite veterans: cameraman Ernest Day, production designer John Box and Frenchman Maurice Jarre, composer on his three previous films. Robert Bolt, his frequent writer, was replaced by Lean himself, who wrote the script.

Lean, who had begun his British career in the 1930s as a film editor, most notably on Pygmalion in 1938, but who hadn’t worked this art since 1942, decided to edit A Passage to India. At the Oscar ceremonies in Los Angeles in March of 1985, the director had high hopes for A Passage to India, which had received eleven nominations including for the picture, the director, the editing and the script. Unfortunately this was the year of the big sweep for Amadeus, and A Passage to India won only two Oscars—Best Supporting Actress for Peggy Ashcroft and Best Original Score for Jarre. Lean’s disappointment was partly responsible for those last inactive years, that and the beginnings of ill health.

After some promising main title music—Jarre augmented a theme from Ryan’s Daughter, a revealing clue why this is not, over-all, one of his better scores—the film begins outside a London steamship ticket office. It’s raining and the army of moving umbrellas recalls a scene in Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Adela Quested (Judy Davis) buys tickets to India, for herself and the mother, Mrs. Moore (Ashcroft), of her fiancé Ronny Heaslop (Nigel Havers). Adela gazes at large photographs of the Taj Mahal and the Marabar Caves, a famous tourist attraction outside the village of Chandrapore, her ultimate destination.

After some promising main title music—Jarre augmented a theme from Ryan’s Daughter, a revealing clue why this is not, over-all, one of his better scores—the film begins outside a London steamship ticket office. It’s raining and the army of moving umbrellas recalls a scene in Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Adela Quested (Judy Davis) buys tickets to India, for herself and the mother, Mrs. Moore (Ashcroft), of her fiancé Ronny Heaslop (Nigel Havers). Adela gazes at large photographs of the Taj Mahal and the Marabar Caves, a famous tourist attraction outside the village of Chandrapore, her ultimate destination.

As the women continue their journey on an Indian train, the theme of Forster’s novel quickly comes to the fore: the clash of cultures between the tens of millions of Indians and the small “garrison” of the ruling British Raj. Onboard are the Turtons, the chief administrator of Chandrapore (Richard Wilson) and his wife (Antonia Pemberton). Mrs. Moore is anxious to meet some of their Indian “friends,” and they politely tell her they don’t associate with the locals.

Soon after their arrival, the ladies attend a garden party. The British dance and enjoy their polo and afternoon tea and ignore their so-called invited Indian “guests,” regarding them with contempt. Mrs. Moore is indignant and says so to her apathetic son: “This is one of the most unnatural affairs I have ever attended. . . . I do not see why you all behave so unpleasantly to these people. . . . The whole of this entertainment is an exercise in power, and the subtle pleasures of personal superiority.”

Soon after their arrival, the ladies attend a garden party. The British dance and enjoy their polo and afternoon tea and ignore their so-called invited Indian “guests,” regarding them with contempt. Mrs. Moore is indignant and says so to her apathetic son: “This is one of the most unnatural affairs I have ever attended. . . . I do not see why you all behave so unpleasantly to these people. . . . The whole of this entertainment is an exercise in power, and the subtle pleasures of personal superiority.”

It is one of the moments, certainly, that helped earn Ashcroft her Oscar.

The school superintendent Richard Fielding (James Fox), however, is a refreshing exception to his countrymen’s arrogance toward the locals. He is friends with a Brahmin philosophy scholar, Professor Godbole (Alec Guinness), and treats a poor widower medical doctor, Aziz Ahmed (Victor Banerjee), as an equal.