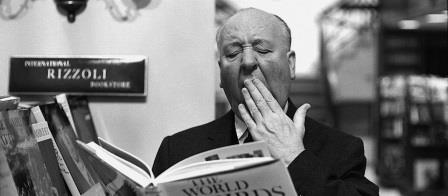

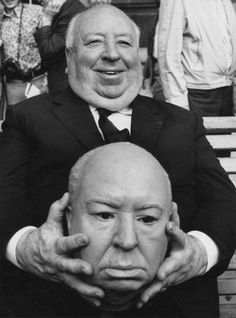

A new biography of the iconic movie director, that “master of suspense” as he came to be known, but also a man of many complex faces, as this biography reveals.

The last Hitchcock book reviewed in these columns, back in 2008, was Donald Spoto’s latest of at least his third take on the director, Spellbound by Beauty, about Hitch’s control of his actresses—sometimes out of control himself—and his special fetish for blondes.

If Peter Ackroyd’s new biography touches upon this darker side of the Hitch persona, even at times delving into it almost with relish, his emphasis is more an overview of the life, hardly brief in years—Hitch lived to be eighty—but brief in Ackroyd’s telling of it. This is the latest, and by far the longest biography, at 260 pages, in the writer’s Brief Lives series, which include such diverse men as Newton, Poe and English painter J.M.W. Turner.

In fact, Hitchcock’s life was as internally self-controlled—restricted, fearful, claustrophobic—as the control he wished to exert upon others. This man, who delighted in frightening moviegoers, and became rich and famous doing it, was frightened himself of many things. As Ackroyd deftly points out, the various phobias include not only, most famous, the fear of policemen, but, more encompassing, the fear of people in general, of being seen walking across a studio commissary, of “being found out,” about whatever, for whatever the reasons.

In fact, Hitchcock’s life was as internally self-controlled—restricted, fearful, claustrophobic—as the control he wished to exert upon others. This man, who delighted in frightening moviegoers, and became rich and famous doing it, was frightened himself of many things. As Ackroyd deftly points out, the various phobias include not only, most famous, the fear of policemen, but, more encompassing, the fear of people in general, of being seen walking across a studio commissary, of “being found out,” about whatever, for whatever the reasons.

A hypochondriac, he disliked human conflict and confrontation, bodily functions, was preoccupied with money, had an inability to admit his own mistakes and was obsessed with neatness. This last often indicates untidiness in one’s character. And, indeed, there were dark secrets.

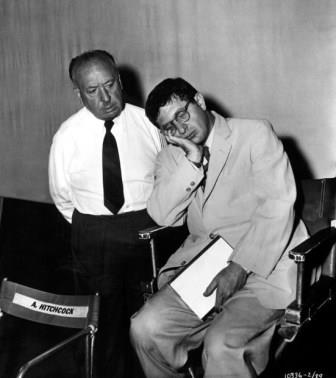

Throughout the biography, Ackroyd emphasizes the director’s inability to thank others, and to presume that he was a one-man team responsible for everything in his films. Even in his so-called “glory” days of the 1950s when he had a string of great films and a fabulous production team—cinematographer Robert Burks, film editor George Tomasini, composer Bernard Herrmann, costume designer Edith Head—the closest he could come to complimenting any of them was “Alma likes it,” Alma being the wife who oversaw everything he did.

Throughout the biography, Ackroyd emphasizes the director’s inability to thank others, and to presume that he was a one-man team responsible for everything in his films. Even in his so-called “glory” days of the 1950s when he had a string of great films and a fabulous production team—cinematographer Robert Burks, film editor George Tomasini, composer Bernard Herrmann, costume designer Edith Head—the closest he could come to complimenting any of them was “Alma likes it,” Alma being the wife who oversaw everything he did.

Hemmed in by his own anxieties, he preferred to be an observer of life rather than a participator. This ideally suits the role of a director who sits outside the scene being filmed, manipulating the actors, but never physically visible on the screen (except for Hitch’s mischievous cameos), influential—controlling—but unseen. Remoteness, suggesting both out-of-sight and aloof, was the essence of Hitchcock’s life. Even on his many vacations he could appreciate the beautiful scenery; he saw it, sure, but, at the same time, was removed from it, viewing it from behind a ski lodge window while reading a book or planning his next movie.

And yet—and yet, as much as he craved attention, and, for instance, far more recognition than as a mere entertainer but as an esoteric auteur as the French saw him, he sometimes resorted to mundane, pathetic behavior before his guests at parties and dinners (he rarely attended the parties of others). He would color all the food blue or hire a stranger as a guest, an old lady, and pretend not to know her, the joke being on his guests, whose aroused curiosity he relished. Sometimes he inflicted cruel jokes on actors whom he envied or wanted to impress, created animosity between his romantic leads to obtain a desired tension on screen or told dirty jokes to his leading ladies to relax them before a take.

And yet—and yet, as much as he craved attention, and, for instance, far more recognition than as a mere entertainer but as an esoteric auteur as the French saw him, he sometimes resorted to mundane, pathetic behavior before his guests at parties and dinners (he rarely attended the parties of others). He would color all the food blue or hire a stranger as a guest, an old lady, and pretend not to know her, the joke being on his guests, whose aroused curiosity he relished. Sometimes he inflicted cruel jokes on actors whom he envied or wanted to impress, created animosity between his romantic leads to obtain a desired tension on screen or told dirty jokes to his leading ladies to relax them before a take.

According to Ackroyd—Spoto was perhaps the first to officially reveal it in depth—the darkest corners of Hitch’s generally dark nature were crisscrossed by sexual shadows—his fascination with rape, already evident in his earliest movies; his risqué jokes, often to observe the reaction of his stars; the many voyeuristic scenes in his films; and his feelings of sexual inadequacy and his envy of some of his leading men, Cary Grant above all, vis-à-vis himself and a body he knew was unattractive and grossly overweight.

Since Alfred Hitchcock’s directorial career began with the silent film—his first nine pictures were just that—the foundation of much of his prowess and sensational success lay in the continuation of many of those techniques. Understatement, perhaps no statement, was the key.

In a number of films, as in Notorious (1946) when Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains are talking on horseback, long shots make conversations inaudible. In North by Northwest (1959), when Cary Grant waits to meet a stranger at a crossroad in flat Midwestern farm country, there continues, seemingly interminably, a long stretch of silence, sans dialogue, music and sound effects, except for passing vehicles. To carry the importance of silence further, it has been estimated that thirty-five percent of Rear Window (1954) is silent.

In a number of films, as in Notorious (1946) when Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains are talking on horseback, long shots make conversations inaudible. In North by Northwest (1959), when Cary Grant waits to meet a stranger at a crossroad in flat Midwestern farm country, there continues, seemingly interminably, a long stretch of silence, sans dialogue, music and sound effects, except for passing vehicles. To carry the importance of silence further, it has been estimated that thirty-five percent of Rear Window (1954) is silent.

Yet, despite Hitchcock’s reliance upon the visual and silence to move a film—“When we tell a story in cinema,” he said, “we should resort to dialogue only when it’s impossible to do otherwise.”—he was not an old-fashioned silent movie director isolated in the past; he was the complete director, one of the most thorough and comprehensive. He was aware of all the other ingredients that make up what’s on screen, not simply the visual, which, yes, is the keynote of Hitch’s style, but the dialogue, the sets (despite his love of rear projection) and the music.

Second to the visual has to be the script. He was most particular about what was said on screen and how it was said. He sought the best, most appropriate writer for each individual film—and he had some good ones: Charles Bennett during his English period, Thornton Wilder for Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Ben Hecht for Spellbound (1945) and Notorious, John Michael Hayes for Rear Window, To Catch a Thief(1955), The Trouble with Harry (1956) and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and Ernest Lehman for North by Northwest (1956) and Family Plot (1976).

Second to the visual has to be the script. He was most particular about what was said on screen and how it was said. He sought the best, most appropriate writer for each individual film—and he had some good ones: Charles Bennett during his English period, Thornton Wilder for Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Ben Hecht for Spellbound (1945) and Notorious, John Michael Hayes for Rear Window, To Catch a Thief(1955), The Trouble with Harry (1956) and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and Ernest Lehman for North by Northwest (1956) and Family Plot (1976).

Almost as often, the director found that some authors fell short of what he wanted, most often novelist who were untrained as screenwriters. Although the names of Raymond Chandler, John Steinbeck and Maxwell Anderson may appear in the screen credits, their contributions were only the basis of the screenplay, which others had to revise, or completely change in some cases.

Ackroyd writes that, from the very beginning, Hitch was acutely aware of sound in the movies and took full advantage of the innovation. In his first “talkie,” Blackmail in 1929, a gossipy neighbor intrudes upon a family and discusses a recent knife killing. As she rambles, her dialogue is slightly muted except when she frequently mentions “knife,” which is emphasized by its clarity. Incidental sounds—the rustling of paper, the wind, the flutter of a bird, a phonograph playing in the background, footsteps on stairs—were carefully notated in the scripts as much as were camera setups and lighting. There is the clang of the cell door inThe Wrong Man (1957) and the noise of a flushing toilet in Psycho (1960)—even then the view of the bathroom fixture was a first-time shocker.

Ackroyd writes that, from the very beginning, Hitch was acutely aware of sound in the movies and took full advantage of the innovation. In his first “talkie,” Blackmail in 1929, a gossipy neighbor intrudes upon a family and discusses a recent knife killing. As she rambles, her dialogue is slightly muted except when she frequently mentions “knife,” which is emphasized by its clarity. Incidental sounds—the rustling of paper, the wind, the flutter of a bird, a phonograph playing in the background, footsteps on stairs—were carefully notated in the scripts as much as were camera setups and lighting. There is the clang of the cell door inThe Wrong Man (1957) and the noise of a flushing toilet in Psycho (1960)—even then the view of the bathroom fixture was a first-time shocker.

And like everything else, Hitchcock knew what he wanted in his musical scores. In Shadow of a Doubt, he instructed composer Dimitri Tiomkin to incorporate Franz Lehár’s “Merry Widow” Waltz, as a leitmotif for the “Merry Widow” murderer who hides out with relatives in a quiet California town. The director, however, was dissatisfied with Tiomkin’s four contributions; the composer found his stride in scoring innumerable Westerns.

Hitch was also generally badly served in his British films, even including the scores for The 39 Steps(1935) and The Lady Vanishes (1938), which, at best, are tepid, only “adequate.” It was not until arriving inHollywood and having at his disposal its more advanced resources that he acquired one of his finest, pre-Herrmann scores, Franz Waxman’s for Rebecca (1940). Even Waxman’s three subsequent scores for Hitch proved below par, the one for The Paradine Case (1947) grossly overblown and inappropriate.

Hitch was also generally badly served in his British films, even including the scores for The 39 Steps(1935) and The Lady Vanishes (1938), which, at best, are tepid, only “adequate.” It was not until arriving inHollywood and having at his disposal its more advanced resources that he acquired one of his finest, pre-Herrmann scores, Franz Waxman’s for Rebecca (1940). Even Waxman’s three subsequent scores for Hitch proved below par, the one for The Paradine Case (1947) grossly overblown and inappropriate.

Not until 1956 and The Trouble with Harry did Hitchcock find in Bernard Herrmann the perfect composer. The two men had much in common—in personalities, shared phobias, pessimistic beliefs that disaster could erupt at any moment—and, from the first, Herrmann seemed to know what the director wanted. So confident was Hitch in his composer, that in his scripts he would often write, “This reel I leave for Mr. Herrmann.”

Herrmann wrote eight scores for the Englishman, counting his consultant status on The Birds (1963), which contains no music score, only bird sounds and electronic simulations. It was for what would have been Herrmann’s ninth score, Torn Curtain (1966), that a misunderstanding irreparably destroyed their friendship. As best can be judged from the conflicting accounts, both men were equally responsible. Hitch was angry that the composer did not write the kind of music he had requested, and Herrmann reacted badly, saying that if Hitch wanted a lighter score and a “pop” tune to fit the times, he had better find someone else.

Herrmann wrote eight scores for the Englishman, counting his consultant status on The Birds (1963), which contains no music score, only bird sounds and electronic simulations. It was for what would have been Herrmann’s ninth score, Torn Curtain (1966), that a misunderstanding irreparably destroyed their friendship. As best can be judged from the conflicting accounts, both men were equally responsible. Hitch was angry that the composer did not write the kind of music he had requested, and Herrmann reacted badly, saying that if Hitch wanted a lighter score and a “pop” tune to fit the times, he had better find someone else.

It was presumably only coincidental that Herrmann’s actual last score marked the beginning of the director’s sad decline. Marnie (1963), starring Sean Connery and Hitch’s new discovery, Tippi Hedren, is now called by some critics a belatedly discovered semi-masterpiece; its artificiality, which had once been so criticized, is exactly what Hitch had intended.

As much as Hitchcock was known for his ability to frighten and shock—not necessarily the same—he was equally famous for the use of the camera, feats which Ackroyd admirably covers. The first attention-getting long crane shot appeared in 1937 in Young and Innocent. From a dance hall lobby, the camera seemingly passes through a wall, moves across the heads of the dancers, focusing on a jazz band, then, closer still, on its drummer and, finally, on his face and twitching eye. In Notorious there is the descending crane shot from a high balcony to a tight close-up of an all-important key in Ingrid Bergman’s right hand. There are countless others.

As much as Hitchcock was known for his ability to frighten and shock—not necessarily the same—he was equally famous for the use of the camera, feats which Ackroyd admirably covers. The first attention-getting long crane shot appeared in 1937 in Young and Innocent. From a dance hall lobby, the camera seemingly passes through a wall, moves across the heads of the dancers, focusing on a jazz band, then, closer still, on its drummer and, finally, on his face and twitching eye. In Notorious there is the descending crane shot from a high balcony to a tight close-up of an all-important key in Ingrid Bergman’s right hand. There are countless others.

In Rope (1948), the “stunt,” as Hitchcock described it, of shooting an entire role of film—ten or eleven minutes—without cutting, and this throughout the entire movie, defeated the concept and effectiveness of the technique. As the director said during François Truffaut’s famous book-long interview in 1965, “I was breaking my own theories on the importance of cutting and montage,” it was “quite nonsensical.”

Then, too, what viewers can forget that other trademark of Hitch’s, the extravagant set pieces, often at well-known landmarks, which end a number of the films. Perhaps either in a certain tongue-in-cheek defilement of hallowed places or as proof that chaos can occur anywhere, the extortionist in Blackmail falls through the glass roof of the British Museum. This foreshadows the race to stop the assassin at Royal Albert Hall in both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, 1956), Norman Lloyd’s fall from the Statue of Liberty in Saboteur (1942) and Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint’s scramble across the faces ofMount Rushmore in North by Northwest.

Then, too, what viewers can forget that other trademark of Hitch’s, the extravagant set pieces, often at well-known landmarks, which end a number of the films. Perhaps either in a certain tongue-in-cheek defilement of hallowed places or as proof that chaos can occur anywhere, the extortionist in Blackmail falls through the glass roof of the British Museum. This foreshadows the race to stop the assassin at Royal Albert Hall in both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, 1956), Norman Lloyd’s fall from the Statue of Liberty in Saboteur (1942) and Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint’s scramble across the faces ofMount Rushmore in North by Northwest.

If a film was without a big climax, then, still, there would be a set piece within the film—the scissors stabbing in Dial M for Murder (1953), the shower knifing in Psycho, the bird attacks in the attic in The Birds. Often these isolated, sensational scenes would be the main impetus for making some films, and Hitchcock could easily spend hours—days—on capturing them in his camera.

There is so much to know about Hitch, just one reason why more books have been written about him than any other movie director. For any in-depth study, Spoto’s The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock is as close as anything to a “sacred text,” but as an introduction to the “master of suspense,” Ackroyd’s survey is highly recommended—for its readability, for some well-expressed insights and for its surprising “thorough” coverage of his subject within the confines of a relatively short book.

A “brief life” to be sure, but Ackroyd makes you want to learn more and offers a tantalizing invitation to see the movies all over again.