“If all these people are not implicated in the crime, then why have they all told me, under interrogation, stupid and often unnecessary lies? Why? Why? Why? Why?”——Hercule Poirot

It’s a long journey by rail from Istanbul to Calais. Even on so luxurious a train as the Orient Express in its glory days of the 1930s. In one such film odyssey, all the passengers make it, not all the way to Calais, “with connections to London,” as announced in the station at the start of the journey, but only to Yugoslavia. All passengers make it through the movie, that is, except one. One is murdered. In a way, murdered twelve times. Twelve stab wounds.

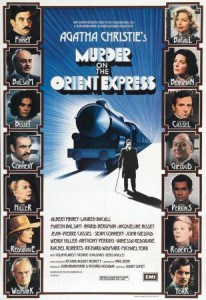

The 1974 Murder on the Orient Express inspired a series of star-studded Agatha Christie films and TV movies. Death on the Nile was the first to follow, in 1978, then came, almost in descending order of quality and production value, at least five more mysteries, including Evil Under the Sun starring [intlink id=”135″ type=”category”]Peter Ustinov[/intlink] and A Caribbean Mystery with Helen Hayes.

The most recent remakes of Orient Express have been two TV movies. The one in 2001 starring Alfred Molina as detective Hercule Poirot is a pale shadow of the ’74 original—almost as expected, the usual “unnecessary” rule regarding remakes in effect here. Considering the usual quality of that BBC/PBS Masterpiece Mystery TV series with David Suchet as the Belgium sleuth, in 2010 came a surprisingly weak version, replete with plot-confusing omissions and shoddy sets, with Suchet merely going through the motions, as if rushed by some budget constraint.

Not that the’74 version of Murder on the Orient Express is without its flaws. True, it has much going for it: resplendent ’30s atmosphere and décor, elaborate period attire, that stellar cast already mentioned, fine ensemble acting by all involved and an elaborate, Oscar-nominated score by Richard Rodney Bennett. Especially according to audience’s need today for glitzy action, superficial character development and little exposition, the film’s major flaw is that it is terribly “British” in its slow, methodical pace, criticized even when the movie first appeared forty years ago.

Not that the’74 version of Murder on the Orient Express is without its flaws. True, it has much going for it: resplendent ’30s atmosphere and décor, elaborate period attire, that stellar cast already mentioned, fine ensemble acting by all involved and an elaborate, Oscar-nominated score by Richard Rodney Bennett. Especially according to audience’s need today for glitzy action, superficial character development and little exposition, the film’s major flaw is that it is terribly “British” in its slow, methodical pace, criticized even when the movie first appeared forty years ago.

The Christie plot is simplicity itself. Like most of her mysteries, there is a murder (sometimes a second or third) and a room full of at least ten suspects—or ship full, or archaeological camp full, or, yes, train full of suspects. Poirot (Albert Finney), then, is left to do his work, with, strangely, no sense of urgency, no awareness of the possibility that other murders might occur.

Following the exuberant, 1930-ish period main title comes a kaleidoscopic montage of distorted scenes, blurred images and newspaper headlines from 1930, recounting the kidnapping and murder of little Daisy Armstrong. The apparent participants include a governess, a military colonel, a maid, a chauffeur, a policeman on his beat, a number of others. (Not coincidentally, Christie’s novel appeared two years after the famous kidnapping and murder, in 1932, of Charles Lindbergh’s twenty-month-old son.)

The film now segues to 1935. The Orient Express has left Istanbul, headed on its northwesterly journey. The first night, en route to Paris, one passenger in the Calais coach, “businessman” Monsieur Ratchett ([intlink id=”155″ type=”category”]Richard Widmark[/intlink]), is found murdered in his compartment bed—stabbed twelve times. Some of the wounds are deep, some rather shallow, others “hardly more than scratches.” Shortly before, Ratchett had asked Poirot to take his case, that he had been receiving threatening letters and sleeping with a gun under his pillow. Interestingly, in the only scene between the two men, viewers learn the proper pronunciation of the detective’s name, not Per-row as Ratchett persists in addressing him, even after corrected, but Pauw-row.

The film now segues to 1935. The Orient Express has left Istanbul, headed on its northwesterly journey. The first night, en route to Paris, one passenger in the Calais coach, “businessman” Monsieur Ratchett ([intlink id=”155″ type=”category”]Richard Widmark[/intlink]), is found murdered in his compartment bed—stabbed twelve times. Some of the wounds are deep, some rather shallow, others “hardly more than scratches.” Shortly before, Ratchett had asked Poirot to take his case, that he had been receiving threatening letters and sleeping with a gun under his pillow. Interestingly, in the only scene between the two men, viewers learn the proper pronunciation of the detective’s name, not Per-row as Ratchett persists in addressing him, even after corrected, but Pauw-row.

As eccentric as another Christie sleuth, Miss Jane Marple, is down-to-earth, Poirot has an abundance of clues. He even remarks over Ratchett’s glassy-eyed body in a sing-song voice, “There are too many clu-u-u-ues in this ro-o-o-om.” Inside and outside the room, the clues include two different pipe cleaners in the ashtray, which also contains a half-smoked cigar; a handkerchief with the letter “H”; a burnt piece of paper; a smashed watch; the drugging of Ratchett’s nightly sleeping potion; the sight of a person in a white kimono disappearing down a passageway; a lost button from a train conductor’s uniform; and a cry, as during a nightmare, from the victim during the night.

As eccentric as another Christie sleuth, Miss Jane Marple, is down-to-earth, Poirot has an abundance of clues. He even remarks over Ratchett’s glassy-eyed body in a sing-song voice, “There are too many clu-u-u-ues in this ro-o-o-om.” Inside and outside the room, the clues include two different pipe cleaners in the ashtray, which also contains a half-smoked cigar; a handkerchief with the letter “H”; a burnt piece of paper; a smashed watch; the drugging of Ratchett’s nightly sleeping potion; the sight of a person in a white kimono disappearing down a passageway; a lost button from a train conductor’s uniform; and a cry, as during a nightmare, from the victim during the night.