“So . . . I got a file on you that goes back further that you’d like to remember and up to where you wish you could forget.” — Police Lt. Collier Bonnabel

Playing a mousy drugstore manager, Richard Basehart’s scheme to become another person so that person can kill his wife isn’t really convincing. His only concession to a disguise—if it can be called that—is to adopt contact lenses instead of his horn-rimmed glasses and wear a flashy suit.

He fools no one. In his new role as Paul Sothern, the girl he starts dating immediately takes a quick, second look when she accidentally meets the undisguised drugstore manager, recognizing him of course but telling the police she’s never seen the man before.

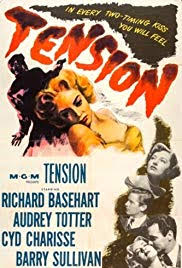

That this is one of the failings of Tension hardly seems to matter. This highly enjoyable film noir is carried by the strong performances, the quick-paced direction of John Berry, the gritty, no-nonsense script of Allen Rivkin and, by no means least, the always contrasting cinematography of Harry Stradling, whose camera intensifies the black-and-white contrasts.

“I’m Collier Bonnabel,” Barry Sullivan says to the camera immediately after the M-G-M trademark lion. “I’m a lieutenant detective in homicide. That’s a fancy name for murder. . . . I only know one way . . . that breaks [suspects] wide open—tension. . . Everybody’s got a breaking point, and when they get stretch so tight, they can’t take it any longer.”

“I’m Collier Bonnabel,” Barry Sullivan says to the camera immediately after the M-G-M trademark lion. “I’m a lieutenant detective in homicide. That’s a fancy name for murder. . . . I only know one way . . . that breaks [suspects] wide open—tension. . . Everybody’s got a breaking point, and when they get stretch so tight, they can’t take it any longer.”

The camera closes in on the ever-stretching rubber band between his thumbs, then the title and complete main title credits.

The narration sound familiar? It’s a close call as to which came first—the premiere of Tension or the initial broadcast of the hit radio show Dragnet when Jack Webb renders a Bonnabel-like, near-monotone recounting of a day’s police duty. Although the two came only five months apart, neither monologue is hardly new, as voice-overs had been used by any number of earlier films, especially noirs.

As Bonnabel stretches the rubber band, he recalls a certain case that now unfolds in flashback. . . .

A bespectacled Warren Quimby (Basehart)—even his name is wimpy—is foolishly, unjustifiably in love with his floozy wife, Claire (Audrey Totter), who runs hot and cold towards him. He saves and scrapes and buys a new house trying to please her, but she is totally unimpressed and won’t even enter the place.

A bespectacled Warren Quimby (Basehart)—even his name is wimpy—is foolishly, unjustifiably in love with his floozy wife, Claire (Audrey Totter), who runs hot and cold towards him. He saves and scrapes and buys a new house trying to please her, but she is totally unimpressed and won’t even enter the place.

Brazenly in front of Warren, she goes out with a rich thug of a man, Barney Deager (Lloyd Gough). Warren confronts the two at Deager’s Malibu beach house, but she rejects him and Deager beats him up.

It’s not until his clerk-assistant Freddie (Tom D’Andrea) casually mentions that if it had happened to him he would have killed Deager that Warren decides he might do just that by way of a new identity.

From Ann Sothern’s picture on the cover of a movie magazine, he decides to become Paul Sothern, a cosmetics salesman. He replaces his glasses with contact lenses, wears a stylish suit and rents an apartment in another part of town. Living in a nearby apartment is lovely Mary Chanler (Cyd Charisse), whom he starts dating.

Soon after Warren’s second visit to Deager’s beach house, where he was prepared to kill him before realizing Claire wasn’t worth it, she inexplicably comes home, saying that Deager has been murdered.

Soon after Warren’s second visit to Deager’s beach house, where he was prepared to kill him before realizing Claire wasn’t worth it, she inexplicably comes home, saying that Deager has been murdered.

Detective Bonnabel and his partner, Lieutenant Gonsales (William Conrad), arrive and question Claire. She is known to have left the murder scene. She says she was only there to swim and that both she and Warren were Deager’s friends. The police are looking for the gun used to kill Deager and for a suspect named Paul Sothern.

Mary, concerned about Sothern’s disappearance, provides the police with a photo of Paul. Bonnabel soon realizes that Sothern and Quimby is the same person.

Sensing something fishy in Claire’s story, Bonnabel pretends to be attracted to her, and later casually mentions that locating the murder weapon could convict Quimby.

Taking the bait, Claire retrieves the revolver from where she had hidden it and slips it under a chair cushion in Sothern’s apartment. Warren and Mary appear, followed by the police. Claire says she was looking for the gun and Bonnabel suggests she continue looking.

When she “finds” it under the cushion, Bonnabel explains that she has just incriminated herself, that all the furnishings had been replaced. Cursing him, Claire is led away. Mary insists that nothing in the room has been moved, and, revealing a ploy worthy of Sherlock Holmes or Columbo, Bonnabel replies, “No. That would’ve been a lot of work, wouldn’t it?”

When she “finds” it under the cushion, Bonnabel explains that she has just incriminated herself, that all the furnishings had been replaced. Cursing him, Claire is led away. Mary insists that nothing in the room has been moved, and, revealing a ploy worthy of Sherlock Holmes or Columbo, Bonnabel replies, “No. That would’ve been a lot of work, wouldn’t it?”

The finishing touch to Tension is André Previn’s score, full of dark rhythms and raw dissonances. Most original, the composer scored an appropriately somewhat sleazy solo saxophone to accompany many of Claire’s screen appearances, much as he would give a racy blues tune to another loose woman, Shirley Jones’ prostitute in Elmer Gantry (1960).

André Previn had been arranging and scoring films for M-G-M since 1947, then an eighteen-year-old wunderkind. Nominated thirteen times during his Hollywood career, he would receive four Oscars for arranging musicals—Gigi (1958), My Fair Lady (1964), etc.—but also for the score of Irma la Douce (1963). Although classified as “arranged,” the music for the Billy Wilder picture was ninety percent Previn’s own creation.

He did compose outstanding purely dramatic scores for Bad Day at Black Rock (1954) and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962), and was nominated for Elmer Gantry.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xHmLlhVqGo[/embedyt]