“I guess if the earth were made of gold, men would die for a handful of dirt.”—— Hooker (Gary Cooper), the closing line of the film

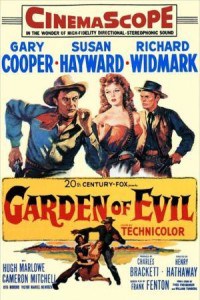

The Garden of Evil that 20th Century-Fox made in 1954, one of the early CinemaScope films released to lure the growing TV audiences back to the theaters, recalls a number of earlier and later films of the same type. The theme of greed is stolen most obviously, though far less imaginatively, from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, made seven years earlier. As to the time-tested rescue-someone-in-distress plot in Garden of Evil, from among many examples The Professionals of 1966 comes to mind as also a better picture. Even Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil has a similar title, though a totally different theme.

Filmed on location in central Mexico with gray mountain vistas to underpin the austere theme, the film had highly qualified artists involved that could have made something of note. It is directed by [intlink id=”7″ type=”category”]Henry Hathaway[/intlink], photographed by Milton Krasner, art direction by Lyle Wheeler and Edward Fitzgerald, edited by James B. Clark and scored by Bernard Herrmann. First in line for the failings of the film is Charles Brackett (along with Saul Wurtzel), usually a reliable producer, but here experiencing an off day. The usual producer, the astute Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck would have probably seen the pitfalls and nixed the entire project. Was he out of town? Otherwise occupied on a casting couch with a starlet? Why his name is absent from the screen credits isn’t clear.

But the central weakness of the film lies at the feet—more accurately in the pens and creative minds—of the three screenwriters. More about that later.

Just remember The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and the plot is basically there—instead of three greedy men after gold, there are four: Hooker ([intlink id=”215″ type=”category”]Gary Cooper[/intlink]), the easygoing ex-sheriff, the moral one who does much of the thinking for the group; Fiske ([intlink id=”155″ type=”category”]Richard Widmark[/intlink]), the watchful observer of things, the most enigmatic of the bunch who will prove the hero in his way; Luke Daly (Cameron Mitchell), the blustery tough guy who is actually the weakest of the band; and Vicente Madariaga (Mexican actor Victor Manuel Mendoza), the local drifter, the first to volunteer for the trek—and for the money.

Now add to the plot of Garden of Evil a woman, Leah Fuller ([intlink id=”278″ type=”category”]Susan Hayward[/intlink]). She provides not only the essential element of the rescue theme but also introduces romance, however tepid. She hires the men to accompany her through Indian country to rescue her husband John (Hugh Marlowe), injured in a gold mine accident. The three Americans, each in his own way, whether through physical assault or aloof scrutiny, are interested in her. She, by contrast, is distant and wary.

In the opening image on screen, the three American men come ashore off the eastern coast of Mexico. En route to the gold fields of California, they have been stranded by a disabled steamer and decide to imbibe at a local cantina. They are approached by Leah, who offers them each $2,000 to rescue her husband. Seduced by immediate money versus the delayed uncertainty of finding gold in faraway California, the five men, including Vicente, set out.

In the opening image on screen, the three American men come ashore off the eastern coast of Mexico. En route to the gold fields of California, they have been stranded by a disabled steamer and decide to imbibe at a local cantina. They are approached by Leah, who offers them each $2,000 to rescue her husband. Seduced by immediate money versus the delayed uncertainty of finding gold in faraway California, the five men, including Vicente, set out.

The over-all scenario is so simple, the subplot of romance so devoid of nuance, that it requires little space to describe, even by this writer. The first forty-five minutes of the film consist of alternate scenes of the travelers either trekking through mountain landscapes or stopping to camp, which requires sessions of humdrum dialogue. Hooker and Fiske have a conversation of little consequence, Hooker and Leah have a tepid one and so on.

During these forty-five minutes, there is one action scene. Luke assaults Leah, but she is able to repel him. On the rebound and angry, Luke challenges Hooker, who quickly proves Luke’s cowardice. After their fight, Luke falling twice into the campfire and being humiliated enough to cry, Hooker comforts him with words of encouragement and his own moistened bandanna for the loser’s battered face. This all suggests that Hooker might well be the one “good guy” among these greedy soldiers of fortune, the one most likely to survive—plot and movie.

Vicente is marking the trail—a machete hack to a tree, stone arrows on the ground and branches forming signposts—but Hooker and Fiske have noticed. “You think,” Hooker asks, “he might wanna make this trip again?” Fiske replies, “He just might wanna get back from this one.” Leah notices Vicente’s action as well and follows behind him, destroying his markers.

Vicente is marking the trail—a machete hack to a tree, stone arrows on the ground and branches forming signposts—but Hooker and Fiske have noticed. “You think,” Hooker asks, “he might wanna make this trip again?” Fiske replies, “He just might wanna get back from this one.” Leah notices Vicente’s action as well and follows behind him, destroying his markers.

Eventually—it’s really not as long as it may seem to the audience—the five riders reach the so-called Garden of Evil, considered the haunt of malevolent spirits by the local Apaches (usually referred to here as “Indians”), and find John Fuller half buried in the mine cave-in. Freed but bed-ridden with a broken leg, he is ministered to by Hooker who fashions a splint and benevolently suggests he be given coffee and hot soup, compassion that never seemed to occur to the others.

Hooker goes for a walk—lovely mountain vistas—and finds an Indian feather and sees a smoke signal in the distance. He warns the party and they make a dash for it that night. Pursued by the Indians, they still stop to make camp. John, who has been belittling his wife, saying she is using the men to her advantage, does an heroic about-face. With Luke’s help, he mounts a horse and dashes off to create a diversion.

Hooker goes for a walk—lovely mountain vistas—and finds an Indian feather and sees a smoke signal in the distance. He warns the party and they make a dash for it that night. Pursued by the Indians, they still stop to make camp. John, who has been belittling his wife, saying she is using the men to her advantage, does an heroic about-face. With Luke’s help, he mounts a horse and dashes off to create a diversion.

Luke is the first to die from Indian arrows, then John, found hanging upside-down. Vicente is next, standing up defiantly, in the best tradition of “Come on, you guys! Kill me!”—all in Spanish of course—before he is brought down by yet another arrow. The three survivors cross the hills and backtrack to the trail along the edge of a canyon precipice. Hooker and Fiske draw cards to see who will stay behind to hold off the Indians; the other will accompany Leah in a race for safety. Fiske is to stay.

When Hooker and Leah are safe on another mountain ridge, he says he must go back, that somehow Fiske had cheated at the cards. Hooker shoots the last two Indians on the way back and finds that Fiske, now critically wounded, had killed the rest. As Fiske is dying, he encourages his partner to settle down with Leah. Hooker returns to Leah and the two . . . well, yes: they ride off together, their mounted figures distant specks in the last of the film’s vast landscapes, the sun setting.

When Hooker and Leah are safe on another mountain ridge, he says he must go back, that somehow Fiske had cheated at the cards. Hooker shoots the last two Indians on the way back and finds that Fiske, now critically wounded, had killed the rest. As Fiske is dying, he encourages his partner to settle down with Leah. Hooker returns to Leah and the two . . . well, yes: they ride off together, their mounted figures distant specks in the last of the film’s vast landscapes, the sun setting.

As Fiske had said, with every sunset someone dies, and with this sunset it is his turn.

The acting is uniformly inconsistent, never really arresting. This is an adventure yarn, and it’s presumed that, early on, it was decided acting would be secondary. Cooper is subdued even for Cooper. He made a better movie, Vera Cruz, also released in 1954, also filmed in Mexico, also set in the mid-nineteenth century and also about greed—the stealing of gold. Cooper was better in Vera Cruz because, for one reason, he had a strong, clearly defined nemesis in Burt Lancaster.

Hayward is strangely unengaging. Note her deadpan speech to Cooper about her husband and the volcanic ash burying all but the church steeple and mine shaft. Even her indifference toward the men is without nuance, little charisma toward Cooper whom she is supposed to love. Perhaps, with the trekking and the landscape interests, there was little time to develop romantic fireworks.

Hayward is strangely unengaging. Note her deadpan speech to Cooper about her husband and the volcanic ash burying all but the church steeple and mine shaft. Even her indifference toward the men is without nuance, little charisma toward Cooper whom she is supposed to love. Perhaps, with the trekking and the landscape interests, there was little time to develop romantic fireworks.

Widmark is reliable as always, credibly drawing for his apathetic character that fine line between moments of fervent commitment and those of distant detachment. Mitchell seems to alternate between poor delivery and flagrant overacting. Hugh Marlowe is—well, Hugh Marlowe, seemingly unemotional when he’s supposed to be emotional, and, as always, hampered by that impassive face.