Examples of the supposed inferiority of film music are endless, but, to begin things here, I always like to cite one which demonstrates the insidious and rather pervasive nature of the prejudice. It’s not as bad as it used to be—thankfully—but, at its worse, back then . . .

Examples of the supposed inferiority of film music are endless, but, to begin things here, I always like to cite one which demonstrates the insidious and rather pervasive nature of the prejudice. It’s not as bad as it used to be—thankfully—but, at its worse, back then . . .

In 1969, in fact, André Previn and the London Symphony released an LP of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia Antartica, his Symphony No. 7, part of Previn’s continuing RCA cycle of the nine symphonies by the composer. The music is assembled, as English music lovers know, from—cover your ears, protect the children!—the composer’s film score for the British-made Scott of the Antarctic (1948), starring John Mills, James Robinson Justice, Kenneth More and Christopher Lee among the better known actors. (As an example, then as now, of the ridiculous over-duplication of the classical repertoire by record companies, Sir Adrian Boult, with the London Philharmonic, was concurrently recording his own cycle for EMI of the Vaughan Williams symphonies!)

In 1969, in fact, André Previn and the London Symphony released an LP of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia Antartica, his Symphony No. 7, part of Previn’s continuing RCA cycle of the nine symphonies by the composer. The music is assembled, as English music lovers know, from—cover your ears, protect the children!—the composer’s film score for the British-made Scott of the Antarctic (1948), starring John Mills, James Robinson Justice, Kenneth More and Christopher Lee among the better known actors. (As an example, then as now, of the ridiculous over-duplication of the classical repertoire by record companies, Sir Adrian Boult, with the London Philharmonic, was concurrently recording his own cycle for EMI of the Vaughan Williams symphonies!)

In that same month of September, Previn’s recording was reviewed in two different, competing classical record magazines—in Stereo Review by William Flanagan and in High Fidelity by Alfred Frankenstein.

Although Flanagan attacked the cinematic origins of the Sinfonia Antartica (Vaughan Williams’ spelling) as the source of its “downright regressive” nature and the way “ . . . it rambles, vamps and sounds padded . . . ,” Frankenstein went directly, if more picturesquely, for the jugular: “ . . . an odor of movie music still clings to its revised form.” Phew-w-w-w—! Both critics agreed: It was inferior music because of its previous life as a film score; had they not known that and assumed that No. 7 had been composed the “normal” way, like any of the other Vaughan Williams symphonies, their evaluations probably would have been quite different, certainly less hostile, less malevolent.

Both magazines are now long defunct, as are the two critics but not Previn nor that much-abused Symphony No. 7.

Surpassing these attacks, there is possibly the most infamous of all film music vilifications. In a review after the New York première, in 1945, of Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Violin Concerto in D, itself comprised of four melodies from three of his film scores (Another Dawn, Anthony Adverse and The Prince and the Pauper), Irving Kolodin—at the time no small voice in “respectable” classical circles—wrote in The New York Sun that the music contained “more corn than gold.” The phrase, however silly and false, has endured, resurfacing in many discussions of the concerto and in reviews of the various recordings. It’s a fine example of a play on words supposed “erudite” critics can’t resist, even to the extent, as possibly in this case, of slanting an entire review, either pro or con, to exploit a gimmick.

Surpassing these attacks, there is possibly the most infamous of all film music vilifications. In a review after the New York première, in 1945, of Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Violin Concerto in D, itself comprised of four melodies from three of his film scores (Another Dawn, Anthony Adverse and The Prince and the Pauper), Irving Kolodin—at the time no small voice in “respectable” classical circles—wrote in The New York Sun that the music contained “more corn than gold.” The phrase, however silly and false, has endured, resurfacing in many discussions of the concerto and in reviews of the various recordings. It’s a fine example of a play on words supposed “erudite” critics can’t resist, even to the extent, as possibly in this case, of slanting an entire review, either pro or con, to exploit a gimmick.

There are many reasons for the still persistent low esteem of film music in some circles. That “odor of movie music” originated in the silent movie days, when piano/organ accompanists borrowed heavily from the classics, logically enough, mostly from the keyboard literature; and, too, there were those notorious manuals of standard emotional clichés to denote fear, love, despair, surprise, etc. Symphony orchestras accompanying this otherwise soundless medium soon became the norm in the big cities, but, here again, the music was seldom even remotely original.

And then, suddenly, the silents learned to talk—and have background music. Initially, the industry bigwigs feared that hearing an orchestra from somewhere “behind” the screen would discombobulate the audiences as to the source of the music. (An amusing footnote: As far into the sound era as 1943 and Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat, someone wondered, whether satirically or not, where the symphonic music came from in the midst of the open sea, the only set in the film, and another person quickly suggested the presence of a camera was no less illogical!) Anyway, when music was first added directly to the film, the use of a score was usually limited to the main title and, if there was one, the end title.

And then, suddenly, the silents learned to talk—and have background music. Initially, the industry bigwigs feared that hearing an orchestra from somewhere “behind” the screen would discombobulate the audiences as to the source of the music. (An amusing footnote: As far into the sound era as 1943 and Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat, someone wondered, whether satirically or not, where the symphonic music came from in the midst of the open sea, the only set in the film, and another person quickly suggested the presence of a camera was no less illogical!) Anyway, when music was first added directly to the film, the use of a score was usually limited to the main title and, if there was one, the end title.

Initially, as ancient as the ooze of the Mesozoic era, a “soundtrack”—an unknown word then, perhaps—became a collection of clips from the classical symphonic repertoire. Particularly in the early horror films, an audience would often hear the storm section from the William Tell Overture by Rossini, or the molto agitato ed accelerando section of Liszt’s Les Préludes, or salient moments from Swan Lake, or, for that matter, any number of the Tchaikovsky symphonies, particularly the Fifth, or another atmospheric overture, that to Weber’s Der Freischütz. As late as 1943, when Hollywood should have been more sophisticated, a fictional opera in the Claude Rains version of The Phantom of the Opera was assembled from the finale of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony!

By the mid-1930s, voluminous music, practically continuously throughout the films, had become the standard in Hollywood. One of these early milestones was Korngold’s first original score, Captain Blood. Due to lack of time, he had lifted parts of two Liszt tone poems and was—what’s that long-lost term, as old as Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar?—“an honorable man” and insisted his screen credit be as the “arranger” of the ensuing music, even though four-fifths of the score was Korngold’s own.

By the mid-1930s, voluminous music, practically continuously throughout the films, had become the standard in Hollywood. One of these early milestones was Korngold’s first original score, Captain Blood. Due to lack of time, he had lifted parts of two Liszt tone poems and was—what’s that long-lost term, as old as Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar?—“an honorable man” and insisted his screen credit be as the “arranger” of the ensuing music, even though four-fifths of the score was Korngold’s own.

Several years earlier, Max Steiner had pioneered wall-to-wall, big-sounding music in his King Kong. Pioneer though he was, he more than most composers contributed to the adverse reputation of film music and to its quickly acquired second-class status. He thought nothing of dropping in borrowed tunes. It’s almost a death-defying feat to find a Steiner score which is an exception to this practice. Westerns and Civil War films were most often susceptible; in Gone with the Wind, Civil War and American popular songs abound, something like thirty-five. (Albeit that that’s what the film’s producer, David O. Selznick, wanted.)

This is not to deny that Steiner has his moments and can write a good tune when he wishes or has to—he was, after all, a Viennese, adept in operetta and, later, Broadway musicals. Although Since You Went Away—to select a score at random—has a lilting main title theme, in the opening of that film, as the camera pans over a telegram, a wedding trip fishing plaque and a bronzed pair of baby shoes, Steiner quotes, respectively, “You’re in the Army Now,” the “Wedding March” from Lohengrin and Brahms’ Lullaby.

Elmer Bernstein once said in an interview, “If there’s a British warship, Steiner writes [‘Rule Britannia’]. That’s an intellectual response. He’s telling the audience this is a British warship.” Maybe this kind of plagiarism is less blatant. Steiner isn’t implying that any of these tunes are his; the audience is usually alert enough to know better.

Elmer Bernstein once said in an interview, “If there’s a British warship, Steiner writes [‘Rule Britannia’]. That’s an intellectual response. He’s telling the audience this is a British warship.” Maybe this kind of plagiarism is less blatant. Steiner isn’t implying that any of these tunes are his; the audience is usually alert enough to know better.

A less innocent plagiarism, however, continues today. How fortunate it would be if some contemporary movie composers were as honest as Korngold in acknowledging their borrowing from others. John Williams is one of the worst culprits and was clearly “inspired” in Star Wars by Gustav Holst’s “Mars” from The Planets and William Walton’s coronation marches, in Raiders of the Lost Ark by a brief motif from the third movement of Debussy’s La Mer and in E.T., the Extra-Terrestrial by Howard Hanson’s “Romantic” Symphony.

A less innocent plagiarism, however, continues today. How fortunate it would be if some contemporary movie composers were as honest as Korngold in acknowledging their borrowing from others. John Williams is one of the worst culprits and was clearly “inspired” in Star Wars by Gustav Holst’s “Mars” from The Planets and William Walton’s coronation marches, in Raiders of the Lost Ark by a brief motif from the third movement of Debussy’s La Mer and in E.T., the Extra-Terrestrial by Howard Hanson’s “Romantic” Symphony.

Another criticism of film music is that its inspiration is “straitjacketed” because the composers work at an assembly line pace, compose to disjointed sections timed within seconds and are subordinate to an already finished medium in which they rarely have a part. The latter restriction is similarly shared by opera and, to a lesser degree, ballet composers. The composers, unless they wish to elaborate at their own will, are restricted by length and content of the libretto or choreography. What about setting a song to an existing text? And which fitful composer hasn’t rushed to meet a première deadline? But few highbrow critics suggest Verdi’s Otello, Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty and Schubert’s “Der Erlköenig” are second-class music because their composers came late to an already created art form.

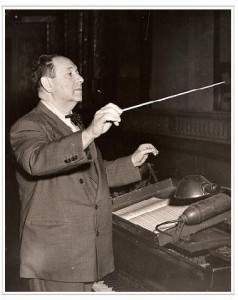

There is also this: In PBS’ 1995 Music for the Movies: The Hollywood Sound John Mauceri emphasized there is an enormous amount of professional jealousy. Many Hollywood composers in the ’30s and ’40s were making a good living—not as much as the big-name stars, of course—while “serious” composers—Bartók and Schoenberg among the most famous—couldn’t get their works performed. Outside of his film music, even Korngold was in the same unhappy position.

Especially irksome to the academic purists—and I sympathize with this detraction—is that hardly any film composer, either in the “Golden Age” or today, orchestrates his own score. Bernard Herrmann then and Howard Shore and Ennio Morricone now are among the few exceptions. Understandable, then, that Herrmann could ask how a respectable composer could relinquish to others such a large part of his creative persona.

Orchestration is a strong ingredient of a composer’s style, his personality, a fingerprint as important as his use of harmony, melody or rhythm, or any other element in the aesthetics of symphonic composition. Imagine the colossal difference if Debussy had turned La Mer over to Grieg to orchestrate, Berlioz his Symphonie Fantastique to Schumann or Richard Strauss his Till Eulenspiegel to Brahms! (Chronologically possible, as the pairs were contemporaries.) Yes, what a travesty if, especially, the two non-master orchestrators, Schumann and Brahms, were to reorchestrate music by two of the greats in the field, Hector Berlioz and Richard Strauss! Would the music be recognizable? Probably, but something striking and original would be missing.

Orchestration is a strong ingredient of a composer’s style, his personality, a fingerprint as important as his use of harmony, melody or rhythm, or any other element in the aesthetics of symphonic composition. Imagine the colossal difference if Debussy had turned La Mer over to Grieg to orchestrate, Berlioz his Symphonie Fantastique to Schumann or Richard Strauss his Till Eulenspiegel to Brahms! (Chronologically possible, as the pairs were contemporaries.) Yes, what a travesty if, especially, the two non-master orchestrators, Schumann and Brahms, were to reorchestrate music by two of the greats in the field, Hector Berlioz and Richard Strauss! Would the music be recognizable? Probably, but something striking and original would be missing.

On the other hand, this deception, or this partnership, if you will, of composer/orchestrator can—accidentally, unintentionally—produce a positive effect. Hearers of John Williams’ scores, for example, forget that a part of the brilliant sound, the sophisticated use of the instruments, is due to his former orchestrator, Herbert W. Spencer, much as Jerry Goldsmith had benefited in his lifetime from Arthur Morton. To find on a soundtrack album Spencer’s credit for E.T. or The Witches of Eastwick, like Morton’s for Patton or The Omen, usually requires some searching.

Okay, it’s true: Korngold didn’t orchestrate his film scores. Therefore he’s suspect, excommunicated? Not necessarily. He left on four staves such detailed instructions for his orchestrators that the resulting ambiance is, miraculously, quintessential Korngold. And a uniformity of technique, especially in the swashbuckling pictures, was maintained because Milan Roder, if not always alone, was at least among the two or three orchestrators on a picture, and they all knew the composer’s style.

And, yes, there is the unalterable reality that many film scores are pretty bad, even in that shimmering, idealized “Golden Age.” Today, with even more mediocre—okay, terrible—films being made, the plethora of undistinguished, out-and-out horrific soundtracks continue unabated. Every film has a soundtrack album, even if the “score” is nothing more than a string of Rock, Heavy Metal or “Pop” songs.

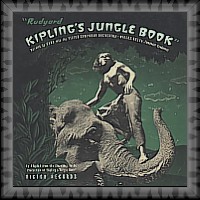

There was a time, in those early days, when certain scores—say, Korngold’s Kings Row, Miklós Rózsa’s Spellbound and Gone with the Wind—were so popular that multitudes of movie-goers would write the studios and ask how to obtain a recording of the music. There weren’t any—not then. Rózsa’s The Jungle Book was the first-ever film score album, released in 1942 on three 78-rpm discs.

There was a time, in those early days, when certain scores—say, Korngold’s Kings Row, Miklós Rózsa’s Spellbound and Gone with the Wind—were so popular that multitudes of movie-goers would write the studios and ask how to obtain a recording of the music. There weren’t any—not then. Rózsa’s The Jungle Book was the first-ever film score album, released in 1942 on three 78-rpm discs.

So just where did—does—film music stand, vis-à-vis the “outside world,” among the “true” arts, in comparison with the “real” ethos of much revered classical music? The worst is implied by Roy Guy in his liner notes to a Korngold Violin Concerto release in 1974: “ . . . a segment of the American critical fraternity seemed to conclude that anyone who was so notably successful in Hollywood”—this goes back to that professional jealousy thing—“couldn’t it naturally followed, have much to offer as a ‘serious’ composer.”

What did film composers themselves think? Korngold, who throughout his life was generally reticent about his Hollywood years, wrote in 1940 in a rare article in Music and Dance in California: “Never have I differentiated between my music for films and that for the operas and concert pieces. Just as I do for the operatic stage, I try to invent for the motion picture dramatically melodious music with symphonic development and variation of the themes.”

Christopher Palmer, the film music scholar—and he was just that, one of the finest, who died prematurely at the age of 48—was, in particular, a champion of Herrmann’s music, which he defended, if “defending” was necessary, by writing, “[An] important point . . . —and one Herrmann has always insisted on—is that he sees no difference between composing for the cinema and composing for any other medium.”

But, hey! These are film composers and film music lovers defending their art. What about comments from some “serious” composers? What about one of the greatest American composers of the twentieth century? Aaron Copland. He, it’s well known, had some negative experiences in Hollywood, not unlike many of his fellow artisans, David Raksin and André Previn as well as Herrmann, but Copland was still able to say, “Hopefully, some day the term ‘movie music’ will clearly define a specific musical genre and will not have, as it does have nowadays, a pejorative meaning.”

But, hey! These are film composers and film music lovers defending their art. What about comments from some “serious” composers? What about one of the greatest American composers of the twentieth century? Aaron Copland. He, it’s well known, had some negative experiences in Hollywood, not unlike many of his fellow artisans, David Raksin and André Previn as well as Herrmann, but Copland was still able to say, “Hopefully, some day the term ‘movie music’ will clearly define a specific musical genre and will not have, as it does have nowadays, a pejorative meaning.”

The history of recorded film scores had one of its biggest surges of interest in the mid-1970s with the release, initially, of “The Sea Hawk,” an LP devoted to a sampling of Korngold’s scores. Charles Gerhardt conducted some of London’s finest orchestral players in an amalgam called the National Philharmonic, and the performances were captured by one of the great engineers, Kenneth Wilkinson, in, to boot, one of the great acoustic venues of the world, Kingsway Hall, London.

The performance quality and milestone sound were maintained in the subsequent releases of the “Classic Film Score” series. At least one LP was devoted to each of Hollywood’s “Golden Age Seven”: besides Korngold, Herrmann and Steiner, there were Miklós Rózsa, Franz Waxman, Dimitri Tiomkin and Alfred Newman. Other LPs highlighted Warner Bros.’ three greatest stars, Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn and Bette Davis, resulting in a compilation approach and the inclusion, as fillers, of some lesser luminaries. An opinion expressed by more than one critic at the time was that Steiner was over-represented, sometimes by his weaker music.

Rózsa and Herrmann benefited from the exposure by an occasional release of their “serious” music, but the real winner was Korngold himself. After decades of obscurity, his symphonic, chamber and operatic music finally became readily available and was acknowledged as the last flowering of Viennese romanticism, the product of one of the great child prodigies, after Mozart, Mendelssohn and Saint-Saëns.

Despite the decline of the crystal-cased CD and the current world financial crisis, the classic film scores of yore have experienced something of a second-wave revival, whether original soundtrack transfers or brand new recordings—and from such labels as Naxos, Chandos, Film Score Monthly, Varese Sarabande and, most recently, Tribute.

Complete scores for many of the “Golden Age” composers include Korngold’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk, the latter in a magnificent two-disc set from Naxos; Steiner’s King Kong and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre; Herrmann’s Mysterious Island and Fahrenheit 451; Newman’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame; Tiomkin’s Red River; and Waxman’s Prince Valiant, a weak film but what music! All of these are newly recorded except the last, which, from Film Score Monthly, has an original soundtrack source. Prince Valiant is mentioned because it’s a great score and a modern version is desperately needed. Record labels, are you listening?!——

As only one instance of the distance film music has come since that Mesozoic ooze, in 1996 Esa-Pekka Salonen, a composer himself and then highbrow conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic (now succeeded by the even more dynamic Gustavo Dudamel), released an entire CD devoted to a composer he admires, Bernard Herrmann. The album is devoted mostly to Hitchcock films, including a score, Torn Curtain, which Hitch rejected, and features two non-Hitchcock films, Herrmann’s Taxi Driver and Fahrenheit 451. Omitted are Citizen Kane, which launched Herrmann’s Hollywood career, and the fantasy films of Ray Harryhausen. Still, it’s a treasure-trove for anyone seeking a nearly ideal introduction to Herrmann’s movie music.

With its classical sales in the cellar, the Chandos label has turned to well recorded, expertly played film music, now with one of the most impressive catalogues in the industry, scores mostly by British composers, i.e., Vaughan Williams, Arnold Bax, Malcolm Arnold, William Walton, Alan Rawsthorne, Richard Rodney Bennett, Clifton Parker, William Alwyn, Richard Addinsell, Ron Goodwin, etc., etc. Yes, quite a remarkable list, especially to a film music lover. The label has an equally fine array of non-Brits: Georges Auric, Dimitri Shostakovich, Francis Chagrin and a tightly packed single disc of the best from Korngold’s Sea Hawk, not that any part of his greatest score isn’t “the best”!

As the late film historian and record producer Tony Thomas wrote, “ . . . Rózsa’s concert version of The Jungle Book might well take its place alongside Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf in the far from overcrowded field of musical stories for children.” Well, that hasn’t happened yet. But a time will come—there’re intimations of it even now—when suites from film scores, lifted out of their sometimes second-class notoriety, will stand with equal integrity alongside suites from Swan Lake, Carmen and Peer Gynt. Discerning people will wonder, Where has this gorgeous music been all these years?

As the late film historian and record producer Tony Thomas wrote, “ . . . Rózsa’s concert version of The Jungle Book might well take its place alongside Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf in the far from overcrowded field of musical stories for children.” Well, that hasn’t happened yet. But a time will come—there’re intimations of it even now—when suites from film scores, lifted out of their sometimes second-class notoriety, will stand with equal integrity alongside suites from Swan Lake, Carmen and Peer Gynt. Discerning people will wonder, Where has this gorgeous music been all these years?

Is this projection possible from film music?! Of course. Many of us sense—“scent”?—that the air seems to be clearing, and maybe someday the “odor of movie music” will have dissipated completely, as rightly it should.

.