“With all my heart, I still love the man I killed.” —Leslie Crosbie (Bette Davis)

Everyone who has seen the film, including any critics worth their salt, has said it has one of the finest opening scenes in all the movies. Unimaginable and critically detrimental in color, in black and white it sets the dark mood and sultry atmosphere perfectly—a Malaysian rubber plantation, a full moon against silhouetted palm trees and local workers suffering the stifling night heat in a bamboo bunkhouse.

The camera, all the while moving left to right, continues on, past the suspiciously drawn curtains of a bungalow and pauses before its wooden steps. A shot rings out, a man runs from inside, a woman follows. After he has fallen down the stairs, she fires shots into the lifeless body, again and again.

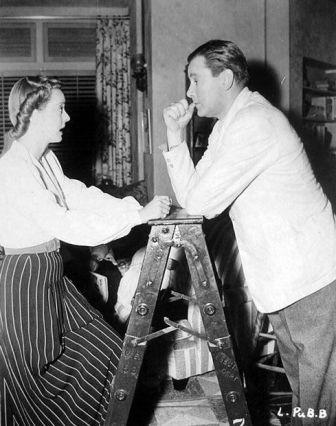

Gaetano Gaudio’s unbroken camera dolly takes only two minutes of screen time; for perfectionist director William Wyler it took all day until it was like he wanted it.

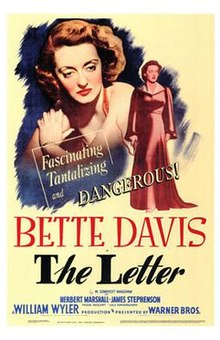

The Letter had a lot going for it at the time—deserving of its seven Oscar nominations—and has emerged as one of Bette Davis’ best films. Although it does border on the “weeper” category of many of her Warner Bros. films of the ’30s and ’40s, the likes of Dark Victory (1939), Now, Voyager (1942) and Mr. Skeffington (1944), The Letter rises above them for the sheer power of Davis’ conniving, deceitful and downright evil performance.

From the beginning, the woman receives little sympathy from the audience—unlikable, but fascinating as a character. Even when first seen, she seems not a nice person. Later, sensing it herself, she will say to her lawyer: “’Cause I’m so . . . so evil.”

From the beginning, the woman receives little sympathy from the audience—unlikable, but fascinating as a character. Even when first seen, she seems not a nice person. Later, sensing it herself, she will say to her lawyer: “’Cause I’m so . . . so evil.”

Leslie Crosbie (Davis) is already lying in her first scene as she relates how she came to shoot Geoffrey Hammond (David Newell), who, in that opening scene, is seen only briefly before he falls down the steps. (He had to fall down the steps eight times before Wyler was satisfied, much as, more than that number of times, Olivia de Havilland had to haul two suitcases up a staircase in The Heiress (1949) before pleasing the director.)

Leslie’s husband Robert (Herbert Marshall) at first supports her defense that she was only defending herself against what she said were the man’s advances: “If you love a person,” he says, “you can forgive anything.”

But her friend and lawyer Howard Joyce (James Stephenson) soon learns the truth and is disgusted: hers was a crime of passion, she admitting being drawn irresistibly to the man. In her prison cell before her trial, Joyce cautions her: “I don’t want you to tell me anything except what is needed to save your neck.”

But her friend and lawyer Howard Joyce (James Stephenson) soon learns the truth and is disgusted: hers was a crime of passion, she admitting being drawn irresistibly to the man. In her prison cell before her trial, Joyce cautions her: “I don’t want you to tell me anything except what is needed to save your neck.”

The go-between (Victor Sen Yung) for the dead man’s widow (Gale Sondergaard) announces that an incriminating letter exists from Leslie to Geoffrey. If Leslie meets the Eurasian woman in her shop, she may have the letter for $10,000. (Yung is Charlie Chan’s Number Two son in the Sidney Toler mystery series.)

Released into her attorney’s custody, Leslie goes to the shop. It is dark and shadowy, with the only sound that of a tinkling wind chime—Wyler had insisted there be no contribution from composer Max Steiner. The widow drops the letter and Leslie is humiliated in having to pick it up at the woman’s feet.

Without this possible evidence, Leslie is acquitted at her trial, but when Robert wants to take money out of their bank account to buy a plantation, Leslie and Howard have to tell him all the money was used for the ransom letter. Realizing his wife had loved the dead man, Robert offers to forgive her if she swears she loves him. At first, she says she does love him, then admits, “With all my heart, I still love the man I killed!”—the most famous line in the movie.

Without this possible evidence, Leslie is acquitted at her trial, but when Robert wants to take money out of their bank account to buy a plantation, Leslie and Howard have to tell him all the money was used for the ransom letter. Realizing his wife had loved the dead man, Robert offers to forgive her if she swears she loves him. At first, she says she does love him, then admits, “With all my heart, I still love the man I killed!”—the most famous line in the movie.

One sultry night—all the nights are sultry in this story—Leslie sees a knife lying on the floor. When it later disappears, she knows the Eurasian woman is intent on killing her. Leslie accepts her fate and goes to the shop again, where, with the go-between’s help—she is killed with the weapon.

It’s an unfortunate last-minute, unsatisfactory turn in the story. The censoring Hays office of the day would not permit to escape unpunished any character who had committed murder and adultery. And, likewise, the murderers of Leslie have to pay, running into the police as they try to escape.

On the surface, and without thorough analysis, Bette Davis would seem the star of The Letter. She holds her own and more, true, but the spirit and mood of the film, why, photographically for one, it’s such a masterpiece, is due to the director. Wyler seems more difficult than usual, a perfectionist who demanded innumerable retakes. Everyone attached to the film had to be perfect. When he wanted more shadows, he had the art department paint them on the floor.

On the surface, and without thorough analysis, Bette Davis would seem the star of The Letter. She holds her own and more, true, but the spirit and mood of the film, why, photographically for one, it’s such a masterpiece, is due to the director. Wyler seems more difficult than usual, a perfectionist who demanded innumerable retakes. Everyone attached to the film had to be perfect. When he wanted more shadows, he had the art department paint them on the floor.

Both Davis and Stephenson had walk-off-the-set arguments with Wyler. In Stephenson’s case, Bette recalled that she would run after him and assure him, “It will be worth it, Jimmy—don’t go. You will give the great performance of your career under Wyler’s direction.” (Stephenson thanked her for it afterward, but died of a heart attack a few months after production ended.)

Bette did “save” the picture in at least one case when Wyler wanted it re-edited to add scenes that would, he thought, make Leslie more palatable. Bette begged him not to, that he would ruin an already great picture and “lose the intelligent audience.” He added only one scene.

She lost, however, more than once. On the critical line about still loving the man she killed, Wyler insisted Leslie say it to her husband’s face. Bette didn’t think a woman would be able to do that. “To this day,” she wrote, “I think my way was the right way. I lost, but I lost to an artist.”

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DsLf-AXyeT8[/embedyt]