If ever true, it’s true here: it’s “a dark and stormy night.” O-O-O-o-o-o—

It’s October. October is Halloween, and the best possible excuse to celebrate is to watch an old fright film. To begin things, what about a motor drive through a storm? How many horror films have thus started? Countless ones. So we arrive at this one house, knock on the door—there’s a cavernous echo from inside, of course—and we’re greeted by, hardly a lovely maid with a friendly smile, but by . . . well, it could be anyone from any number of movies and Gothic novels.

In this case—by some strange coincidence—we find ourselves in the plot of The Old Dark House. Which means we’re greeted, neither by the aforementioned young lady nor anybody as inviting, but by a bearded, wild-eyed man with an unintelligible mumble. Do we run in fear? Ask for our money back, change channels? . . .

No, as Alfred Hitchcock said so often, “It’s only a movie.” No, we stay and meet some of the old gang from the horrors, this particular gang anyway. After all, if the people we’ll meet—those already there and those who will arrive later, as uninvited guests always do in these films—if they aren’t part of any famous horror “gang,” like those from the Universal or RKO folks, then, to their credit or chagrin, they’ve appeared in at least one horror movie.

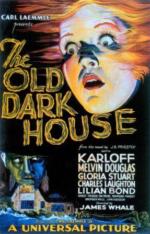

The few full-fledged horror society members in The Old Dark House who could be regarded as part of a “gang”—Boris Karloff, Ernest Thesiger and Gloria Stuart—have been assembled by their gang leader, that master of the macabre, Englishman James Whale. This is his second horror film. The year before, Frankenstein had begun his great trilogy in the genre that includes The Invisible Man (1933) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

The few full-fledged horror society members in The Old Dark House who could be regarded as part of a “gang”—Boris Karloff, Ernest Thesiger and Gloria Stuart—have been assembled by their gang leader, that master of the macabre, Englishman James Whale. This is his second horror film. The year before, Frankenstein had begun his great trilogy in the genre that includes The Invisible Man (1933) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

The Old Dark House falls just a bit short of being in this esteemed company, but it’s still fascinatingly suggestive of things to come. Critic William K. Everson wrote that it was better the second time and “is one of the real masterpieces of its genre.” In the film’s general milieu and the style of the sets, it’s obviously from Universal and from producer Carl Laemmle (Jr.). A horror gang member with undeniable credentials, he produced not only Whale’s great trio but also Dracula (1931), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), The Mummy (1932) and many other similar titles.

Cinematographer Arthur Edeson, though perhaps more versatile, with a wider scope of genres than either Whale or Laemmle, shooting such diverse films as The Maltese Falcon (1941) andCasablanca (1942), does occasionally turn his camera toward the strange and terrible—in The Invisible Man and Frankenstein. The Old Dark House contains some of his finest work.

In 1932, nearly all film scores were limited to opening and closing titles. But in 1933, coming from RKO and with practically continuous music by Max Steiner, King Kong was something of an exception to the rule, an aberration, even. Producers were still worried that audiences would wonder where the music was coming from. While ground-breaking by its mere premature appearance, Steiner’s music isn’t particularly original.

In 1932, nearly all film scores were limited to opening and closing titles. But in 1933, coming from RKO and with practically continuous music by Max Steiner, King Kong was something of an exception to the rule, an aberration, even. Producers were still worried that audiences would wonder where the music was coming from. While ground-breaking by its mere premature appearance, Steiner’s music isn’t particularly original.

In The Old Dark House, the main title is by the obscure David Broekman. With no score heard again until the stock music of the end title, it’s assumed that the atmosphere, especially compared with the wall-to-wall scoring of later horror films, would be deprived of an essential support. True in most cases, but here, taking music’s place, is the sound of rain and thunder, rustling curtains, banging shutters, slamming doors, creaking stairs and footsteps on hard floors.

For the first thirty-five minutes or so, nothing untoward really happens—a lot of talking and those unsettling sounds. The screenplay, by Benn W. Levy, is based on Benighted by J. B. Priestley (not “Priestly” as listed in the credits), and additional dialogue is by R. C. Sherriff. Whether from Priestley or Sherriff, the lines are often kinky and satirical, some even nonsensical, with presumed influence from Mr. Whale.

These characters and their actor-re-creators combine to make a simple enough plot. There is an intentional pairing of the five weirdos of the household against the five strangers who, startlingly normal by contrast, show up to escape the pestilential rain.

These characters and their actor-re-creators combine to make a simple enough plot. There is an intentional pairing of the five weirdos of the household against the five strangers who, startlingly normal by contrast, show up to escape the pestilential rain.

But back to that fearsome man at the door. . . .

The Wavertons, man and wife, have driven through the storm in the Welsh countryside—Margaret (Stuart; her horror film credits include The Invisible Man and The Prisoner of Shark Island, 1936) and Philip (Raymond Massey, Arsenic and Old Lace, 1944). With them, in the back seat, is their friend, Roger Penderel (Melvyn Douglas).

They had knocked on the door and been greeted by the mumbling Morgan (Karloff). Now the head of the house, the quirky Horace Femm (the skeletal Thesiger, The Bride of Frankenstein, many more), comes to the door. Inside, the Wavertons meet Horace’s crabby sister Rebecca (Eva Moore), who will later tell Margaret that living with them is her aged father, Sir Roderick Femm (played by actress Elspeth Dudgeon, complete with beard!, and listed in the main title as John Dudgeon).

Then through the rainy night come two more travelers, Sir William Porterhouse (Charles Laughton, Island of Lost Souls, 1932, and The Strange Door, 1951) and his girlfriend Gladys DuCane (Lilian Bond).

A lot begins to happen after those first thirty-five minutes, which have set the stage and titillated the audience with anticipation. Roger romances Gladys, to Sir William’s indifference. Hearing a voice like a child’s, Margaret and Philip discover Roderick in bed. He warns them that an arsonist, his eldest son, Saul (Brember Wills), is locked in an upstairs room—overtones of the imprisoned wife in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

A lot begins to happen after those first thirty-five minutes, which have set the stage and titillated the audience with anticipation. Roger romances Gladys, to Sir William’s indifference. Hearing a voice like a child’s, Margaret and Philip discover Roderick in bed. He warns them that an arsonist, his eldest son, Saul (Brember Wills), is locked in an upstairs room—overtones of the imprisoned wife in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

Morgan sets Saul loose. The clearly deranged Saul knocks Roger out and sets fire to a curtain. When Roger regains consciousness, the two fight and fall from a balcony. With Roger injured, Morgan tenderly cradles the dead Saul, then takes the body upstairs.

The storm finally over by morning, Gladys and Sir William tend to the injured Roger while Margaret and Philip drive off to find an ambulance. As the Wavertons leave, Horace sardonically bids them farewell: “Goodbye. Goodbye. Bye. Bye. Nice to have met you.” As if nothing has happened. When Roger awakens, he asks Gladys to marry him.

But what of that wandering, mumbling Morgan? And, oh—don’t forget!—Horace and his sister are still there, too, in this old dark house, perhaps ready to make mischief for any travelers who might—shall we say?—“foolishly” seek refuge from that next storm.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9-Jh8IjRyKI[/embedyt]