“As for you Strauss, I’m going to give you the brain of the wolf man so that all your waking hours will be spent in untold agony awaiting the full of the moon . . . which will change you into a werewolf.”—— Dr. Niemann (Karloff)

It is hard to tell with Universal Pictures, difficult to keep track of the myriad, seemingly endless horror films, especially during the 1930s and ’40s, at least one film a year.

The studio’s best sound films came in the ’30s, beginning with Dracula and Frankenstein, both in 1931. Then followed The Old Dark House and The Mummy, the best two releases of that bumper crop year, 1932, which included at least four exceptional horror productions. The Invisible Man, with its then amazing special effects, appeared in 1933. The decade peaked in 1935 with The Bride of Frankenstein, not only a great horror film, but a great, milestone film, period. And, to close the ’30s, Son of Frankenstein in 1939.

Although the horror film was still in vogue, the ’40s brought a discernible decline, both in the number of releases and, more crucially, in the quality of the films. While interesting in its own right, The Invisible Man Returns (1940) was a pale sequel after its Claude Rains predecessor. A high point, though, was The Wolf Man (1941), recalling the glories of the ’30s, and Lon Chaney, Jr.’s first stint as the tormented man-turned-werewolf, for, yes, “even a man who’s pure in heart and says his prayers at night . . . ”

Universal’s frequent turn to horror comedies had been highly successful in 1939 with Bob Hope’s The Cat and the Canary, and continued into the ’40s with The Invisible Woman (1940) and Hold That Ghost (1941), the first in the horror genre by comedy team Bud Abbott and Lou Costello.

Universal’s frequent turn to horror comedies had been highly successful in 1939 with Bob Hope’s The Cat and the Canary, and continued into the ’40s with The Invisible Woman (1940) and Hold That Ghost (1941), the first in the horror genre by comedy team Bud Abbott and Lou Costello.

There also emerged a trend, sometimes tepidly executed, toward the serious and the non-monster movie, more adult fare. The Uninvited (1944) featured a mere filament of a floating ghost, which was dispatched with some stern words from non-horror star Ray Milland. Another remake of The Phantom of the Opera (1943), now in color, starred Rains who wreaked havoc on an opera house. And The Unseen (1945), an early take on the serial killer, showcased a human monster, with still more non-horror stars, Joel McCrea and Gail Russell.

In the 1950s Universal had abandoned Dracula, the Frankenstein monster, the werewolf and the Mummy. In their places, from Universal and other studios, now came aliens from outer space and insects and cephalopods giganticized by radiation from man’s mishandling of things beyond his understanding. But this is entirely another offspring of the horror film, for discussion at another time.

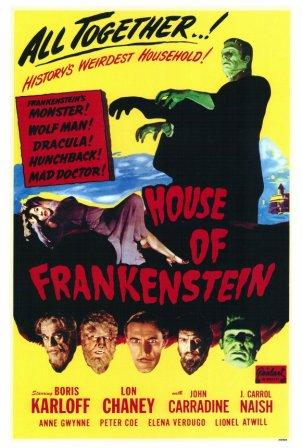

Returning to the ’40s, by the time of The House of Frankenstein—the gang’s all here in this one except the Mummy!—the Dracula-Frankenstein-Wolf Man movies had so overlapped, intermingled and been repeatedly rehashed that little, if anything, new remained to say—or show.

Returning to the ’40s, by the time of The House of Frankenstein—the gang’s all here in this one except the Mummy!—the Dracula-Frankenstein-Wolf Man movies had so overlapped, intermingled and been repeatedly rehashed that little, if anything, new remained to say—or show.

This, however, didn’t prevent production on House, and for the possible few in the audience who might be unfamiliar with the stories, lectures were deemed necessary. George Zucco, in his brief screen time, explains, as if anew, the Dracula legend, and Boris Karloff informs new viewers and reminds the old ones about the Frankenstein monster’s origins and social interaction problems. It could be assumed that if someone is so inclined to watch House, he would have seen the earlier films and been familiar with it all.

If there were any ways for these plots and stories to be reinvigorated, or at least done with a new approach, Universal didn’t use them. House is, in fact, two movies. The first—and better—half is about Dracula and the Frankenstein monster; the second half concerns another of poor, distressed Larry Talbot’s search for a cure for his hypertrichosis, this serious wolf transmutation.

Compared with most of the scores in these films, Hans J. Salter, now aided by an uncredited Paul Dessau, produces a less horror-sounding main title. Eliminated, too, is that camera roaming the traditional fog-drenched woods, most memorable in The Wolf Man, now replaced by a matte of a non-threatening blur, which seems to complement the more lyrical moments of this particular main title.

Compared with most of the scores in these films, Hans J. Salter, now aided by an uncredited Paul Dessau, produces a less horror-sounding main title. Eliminated, too, is that camera roaming the traditional fog-drenched woods, most memorable in The Wolf Man, now replaced by a matte of a non-threatening blur, which seems to complement the more lyrical moments of this particular main title.

Even before the fading of the final credit, “Directed by Erle C. Kenton,” the film has already begun. A team of four horses is pulling a two-wagon caravan through a rainy night. As the first wagon passes in a close-up—the distorted reflection of studio lights clearly visible on its smooth surface—painted on the side is “Professor Lampini’s Chamber of Horrors.”

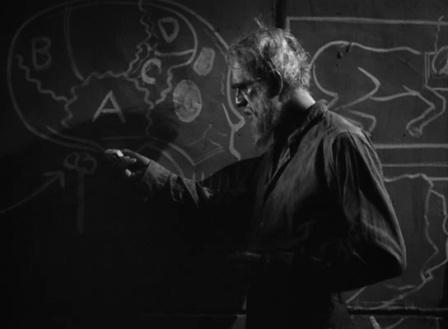

The caravan, to be seen later, passes by the gates of Neustadt Prison, where, inside, a guard (Charles Wagenheim), accompanied by lumbering bassoons, is bringing food to one of the prisoners. When the guard opens the small window of the cell door, an arm reaches out and grabs him in a choking hold. “Now will you give me the chalk?” Just like this man to demand chalk when a common criminal would have insisted on the keys to his cell!

Now with his chalk and blackboards, Doctor Gustav Niemann (Karloff) illustrates how Dr. Frankenstein might have gone wrong in severing the monster’s spinal cord at the base of the skull. In an adjoining cell, his one student, so to speak, is hunchback Daniel (J. Carrol Naish), a low-key hysteric (if such is possible) who will soon be humbly calling Niemann “master” and be all too willing to do his bidding.

Now with his chalk and blackboards, Doctor Gustav Niemann (Karloff) illustrates how Dr. Frankenstein might have gone wrong in severing the monster’s spinal cord at the base of the skull. In an adjoining cell, his one student, so to speak, is hunchback Daniel (J. Carrol Naish), a low-key hysteric (if such is possible) who will soon be humbly calling Niemann “master” and be all too willing to do his bidding.

Niemann’s objective, as he tells Daniel, is to retrieve Dr. Frankenstein’s records from his castle which, keen viewers will remember, was flooded at the end of Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), drowning both the monster and the Wolf Man.

Fate, with a little help from the screenplay, generates a timely storm and lightning brings down part of the prison. Niemann and Daniel escape through the woods, only to come upon Lampini’s caravan, stuck in the mud. What a coincidence! With the escapees’ help, Professor Lampini (Zucco) frees the wagons. When Lampini says he has no intention of going to Reigelberg, not to Vasaria where Niemann is headed, the doctor has Daniel kill the showman.

As the caravan rattles toward Reigelberg—all the carriages in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories “rattle”—Niemann assumes Lampini’s identity, telling Daniel, “All the protection of a traveling show . . . free to move on to those for whom I have unloving memories . . . ” He has several scores to settle with old enemies, including the bürgemeister of Reigelberg, Hussman (Sig Ruman, best remembered as the barracks guard in Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17, 1953).

An effective screen dissolve and Hussman is playing chess with Police Inspector Arnz (a rather tame part this time around for horror staple Lionel Atwill). Enter the bürgemeister’s son Karl (Peter Coe) and his American wife Rita (Anne Gwynne). She invites them to a visiting show of horrors. “Spooks, ghouls, vampires,” she jokes.

An effective screen dissolve and Hussman is playing chess with Police Inspector Arnz (a rather tame part this time around for horror staple Lionel Atwill). Enter the bürgemeister’s son Karl (Peter Coe) and his American wife Rita (Anne Gwynne). She invites them to a visiting show of horrors. “Spooks, ghouls, vampires,” she jokes.

Apparently it is during Niemann’s first show that things turn uncomfortable. About the time Hussman is thinking Niemann looks familiar, the mad doctor shows the audience Dracula’s skeleton, snug in its coffin, and boasts, “If I were to remove this stake . . . ”

Perhaps doubting the power of the Dracula curse, or because of a mental lapse, Niemann does absentmindedly remove the stake from between the skeleton’s ribs, lifting it toward Hussman. But, then, he’s distracted. In the first of Universal’s (John P. Fulton’s) special effects in the film, the skeleton materializes into the corporeal Dracula (John Carradine). Dracula agrees to serve Niemann when the doctor threatens to reinsert the stake: “I’ll send your soul back to the limbo of eternal waiting.”

After Dracula has seduced Rita, enticing her with his finger ringer that sends her into a mesmeric trance, seeing people “who are dead yet alive,” Niemann destroys Dracula’s coffin and its nighttime occupant perishes in the sunlight. End of the so-called “first movie.”

After Dracula has seduced Rita, enticing her with his finger ringer that sends her into a mesmeric trance, seeing people “who are dead yet alive,” Niemann destroys Dracula’s coffin and its nighttime occupant perishes in the sunlight. End of the so-called “first movie.”

Now, onward, to Frankenstein’s castle with all haste! And surprise! Niemann and Daniel find, without much trouble, the bodies of the monster (Glenn Strange) and the Wolf Man (Chaney), frozen in the waters, though, strange, the surrounding climate is warm enough for shortsleeves! (No, no—such incongruities aren’t questioned in horror films and the most faithful devotees of the genre take all these in stride.)

Niemann thaws the two bodies, again without much trouble, and promises to cure the Wolf Man of his full moon hang-up. Meanwhile, Daniel has taken a fancy to gypsy girl Ilonka (Elena Verdugo), whose mind seems numb to the unsavory hunchback. She is more interested in Talbot, and numb, again, now to this guy’s own problem. Anyway, Talbot kills Ilonka during a werewolf spell, but she kills him with a silver bullet before she dies.

Will those who are left be disposed of as well? Niemann has dragged his feet in his promise to restore Daniel’s deformed body, and now Daniel believes his master is responsible for Ilonka’s fate and turns on him. But the monster throws him out the window, and carries the half-conscious Niemann through the woods, pursued by the angry villagers, the familiar torches at the ready.

Will those who are left be disposed of as well? Niemann has dragged his feet in his promise to restore Daniel’s deformed body, and now Daniel believes his master is responsible for Ilonka’s fate and turns on him. But the monster throws him out the window, and carries the half-conscious Niemann through the woods, pursued by the angry villagers, the familiar torches at the ready.

In restoring the monster to life, Niemann apparently neglected to improve its mental capacities, for when the good doctor warns this giant, “Don’t go this way. Quicksand! Quicksand!,” the monster heeds not a word, and——

Not to worry. Next year, 1945, the Frankenstein monster, Dracula and the Wolf Man will have a whole new beginning, another rebirth, in The House of Dracula, all creatures played by the same actors from House of Frankenstein.