“We shall play a little game, Vitus. A game of death, if you like . . . ”—— Boris Karloff to Bela Lugosi

First off, to set things straight and orient any readers venturing into unfamiliar horror film territory, this Black Cat is the 1934 version with Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, not the 1942 version with Basil Rathbone and Broderick Crawford. Nor the 1981 version with Patrick Magee as a man who can communicate with the dead. Nor, to go even further afield—the comparative quality continues to drop—the 1978 Japanese TV serial episode, The Black Cat Murder Case directed by Yûsuke Watanabe.

Rest assured, The Black Cat of 1934 is the best of the lot, the first of eight films the two actors would make together.

A second point of clarification, none of these films have anything to do with Edgar Allan Poe’s short story of the macabre, about the man who, in the first paragraph, assures his reader that he is sane, yet witnesses the return of Pluto, the black cat he thought he had killed. The film’s German director, Edgar G. Ulmer, best known for the 1945 noir Detour, admitted that he selected the title purely as a draw for the box office. (In England, the film was originally released under the title, The House of Doom, for there a black cat was then—now?—considered a good sign.) Ulmer also assisted with the screenplay and art direction, and designed the costumes.

The weakest part of Universal’s 1934 The Black Cat, aside from its lack of humor, is its plot. The film has many other positives, among them excellent acting by the two principals, atmospheric cinematography, original sets and, not least of all—in most respects—a deft “treatment” of ready-made music. The following is an attempt to convey the plot, or what is presumed to be happening in this movie:

Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff), an intellectual and architect, lives in a modernistic house of his own design, a house full of gadgets. To add to the macabre, it’s built over the ruins of an Austrian fort, which he had betrayed during World War I. Leader of a satanic cult, he has preserved the bodies of several beautiful women in glass cases, one whose extended coiffure resembles the bride’s in The Bride of Frankenstein five years later.

Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff), an intellectual and architect, lives in a modernistic house of his own design, a house full of gadgets. To add to the macabre, it’s built over the ruins of an Austrian fort, which he had betrayed during World War I. Leader of a satanic cult, he has preserved the bodies of several beautiful women in glass cases, one whose extended coiffure resembles the bride’s in The Bride of Frankenstein five years later.

The second major character, Vitus Werdegast (Lugosi), a Hungarian psychiatrist, has arrived at the house with a newly wedded couple, the Alisons, Peter (David Manners), a mystery writer, and Joan (Jacqueline Wells, later known as Julie Bishop). He had met them en route on the Orient Express, whose imminent departure is vividly established in a few limited shots. Werdegast, who has spent fifteen years in a prison camp following the war, is traveling to see an “old friend” and discover, if he can, how his wife Karen died.

No, don’t get ahead. . . .

After the transfer from the train, Joan is injured in the wreck of a bus the three had shared. As so often happens in the movies, Poelzig’s house is conveniently nearby. Werdegast treats her with a hallucinatory drug, resulting in some strange but temporary behavior, which seems a pointless plot device, but supposedly meant as a red herring to give a misleadingly sinister aura to Werdegast. The psychiatrist accuses Poelzig of betraying the fort and stealing his wife Karen while he was in prison.

After the transfer from the train, Joan is injured in the wreck of a bus the three had shared. As so often happens in the movies, Poelzig’s house is conveniently nearby. Werdegast treats her with a hallucinatory drug, resulting in some strange but temporary behavior, which seems a pointless plot device, but supposedly meant as a red herring to give a misleadingly sinister aura to Werdegast. The psychiatrist accuses Poelzig of betraying the fort and stealing his wife Karen while he was in prison.

The only black cat connection is the feline seen creeping about in the shadows on occasions and which Werdegast, afraid of cats, kills. As in the Poe story, another cat, or the same cat—it’s not made clear in the film—reappears later.

Poelzig suggests to Werdegast that sometime they must play a game of . . . death. A game they do play is chess: the winner—Poelzig—will take possession of Joan. Poelzig shows his collection of perfectly preserved dead women to his guest, now seemingly quite civilized after his earlier anger toward his host. One preserved corpse is Werdegast’s wife, whom Poelzig says he also loved. Unfortunately, he adds, Werdegast and his wife’s daughter has died. Turns out later, the daughter (Lucille Lund), also named Karen, is very much alive—and is, in fact, Poelzig’s wife.

Poelzig suggests to Werdegast that sometime they must play a game of . . . death. A game they do play is chess: the winner—Poelzig—will take possession of Joan. Poelzig shows his collection of perfectly preserved dead women to his guest, now seemingly quite civilized after his earlier anger toward his host. One preserved corpse is Werdegast’s wife, whom Poelzig says he also loved. Unfortunately, he adds, Werdegast and his wife’s daughter has died. Turns out later, the daughter (Lucille Lund), also named Karen, is very much alive—and is, in fact, Poelzig’s wife.

No, don’t get ahead. . . .

On the “dark of the moon,” Poelzig holds a satanic ritual to sacrifice Joan to Lucifer. He “plays”—what else in a horror movie?—J.S. Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, and later John Carradine also “plays” the piece: for both, their keyboarding is mismatched with the music. Poelzig’s delivery of Latin incantations, largely unrelated phrases (“humanum est errae”/“to err is human” and the like), are interrupted by Werdegast and his bulky servant (Egon Brecher), who free Joan.

Poelzig flees to a sub-basement. After a struggle, Poelzig is subdued by Werdegast who does as he threatens, to “bare the skin from his body.” After Poelzig screams his last and dies, the psychiatrist is shot by Peter, thinking he is harming Joan, while actually he was trying to help. Man and wife flee the doomed house, recalling Poe’s tale The Fall of the House of Usher and its narrator’s escape from that edifice, “the mighty walls rushing asunder.” The wounded Werdegast detonates a stash of explosives hidden under the house. With a five-minute delay, he has time to proudly muse, “It has been a good game.”

Poelzig flees to a sub-basement. After a struggle, Poelzig is subdued by Werdegast who does as he threatens, to “bare the skin from his body.” After Poelzig screams his last and dies, the psychiatrist is shot by Peter, thinking he is harming Joan, while actually he was trying to help. Man and wife flee the doomed house, recalling Poe’s tale The Fall of the House of Usher and its narrator’s escape from that edifice, “the mighty walls rushing asunder.” The wounded Werdegast detonates a stash of explosives hidden under the house. With a five-minute delay, he has time to proudly muse, “It has been a good game.”

Although something of an anticlimax, the film ends with a traditional comic rounding off seen often in movies. Perhaps everybody involved in the production felt that, after all the unrelenting gloom and stalking menace, a little humor couldn’t hurt, even this late. Peter and Joan are on another train, now toward their original destination. From the newspaper, he reads a review of his latest book, Triple Murder. Seems the critic felt that Peter’s story was too fantastic, that perhaps he should stick to reality. After what they have just experienced, certainly fanciful but all too real, the husband and wife look at one another and share knowing smiles.

Werdegast in The Black Cat, Bela Lugosi’s fifteenth film after Dracula in 1931, may be, as many have suggested, the actor’s finest role. His acting is unusually restrained and multi-textured, more so than Karloff’s. At passing moments, a benevolent, unthreatening manner arises. At one point, Joan, in her distress over Peter’s absence, falls willingly into his comforting embrace. The audience may feel a tug of sympathy for him, even if, at this point, they sense, or assume, he is one of two possible villains. (What Werdegast does to Poelzig clearly qualifies him as a villain.) Lugosi would demonstrate further acting of this caliber, if less varied, as Igor, the loyal aid of the scientist’s once again resurrected creature, in The Son of Frankenstein in 1939.

Werdegast in The Black Cat, Bela Lugosi’s fifteenth film after Dracula in 1931, may be, as many have suggested, the actor’s finest role. His acting is unusually restrained and multi-textured, more so than Karloff’s. At passing moments, a benevolent, unthreatening manner arises. At one point, Joan, in her distress over Peter’s absence, falls willingly into his comforting embrace. The audience may feel a tug of sympathy for him, even if, at this point, they sense, or assume, he is one of two possible villains. (What Werdegast does to Poelzig clearly qualifies him as a villain.) Lugosi would demonstrate further acting of this caliber, if less varied, as Igor, the loyal aid of the scientist’s once again resurrected creature, in The Son of Frankenstein in 1939.

By the time of the mid-’50s and such atrocities as Glen or Glenda and Bride of the Monster, directed by the infamous Edward D. Wood, Jr., the most untalented man in movie history, Lugosi had become the victim of his growing penchant for accepting just any script handed him and had descended, now irredeemably, into drug abuse.

As for Boris Karloff, his screen persona in The Black Cat is the opposite of Lugosi’s—subdued, slow-speaking and moving about, dressed in priestly black, like a male incarnation of Mrs. Danvers (Edith Anderson) in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca. Karloff seems subservient to Lugosi much of the time, but his quieter voice carries weight, especially evident during the chess game. He even changes the tone of his voice, often deceptively reassuring. While Lugosi has no eccentric makeup, Karloff has been given dark eyes, an elongated face, exaggerated ears and a pointed hairline that reaches half way down his forehead.

As for Boris Karloff, his screen persona in The Black Cat is the opposite of Lugosi’s—subdued, slow-speaking and moving about, dressed in priestly black, like a male incarnation of Mrs. Danvers (Edith Anderson) in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca. Karloff seems subservient to Lugosi much of the time, but his quieter voice carries weight, especially evident during the chess game. He even changes the tone of his voice, often deceptively reassuring. While Lugosi has no eccentric makeup, Karloff has been given dark eyes, an elongated face, exaggerated ears and a pointed hairline that reaches half way down his forehead.

Karloff, who made more movies than Lugosi and lived long enough to venture successfully into television, also had a greater range than his fellow actor. Even securely typecast in horror films, he was able to vary and shade his villainy. Beyond the various films featuring the Frankenstein monster, yet still within the horror genre, there is quite a spectrum of nuance among the doctor-scientist in The Invisible Ray, Grigor, the evil twin brother in The Black Room, the head executioner in The Tower of London (1939), Gray, the digger of corpses in The Body Snatcher, the cruel asylum director in Bedlam (1946) and, in the “later Karloff era,” the vampire in The Wurdulak, the best of the horror tales in Mario Bava’s Black Sabbath (1964) trilogy.

As for the typecasting, Karloff was grateful for it. “They tell me I’m typecast,” he said. “Well, I’ve been fortunate. Actors are extremely lucky to be typecast, like any tradesman who is known for specialization. It is a trademark, a means by which the public recognizes you. . . . The monster was, indeed, the best friend I could ever have.”

As for the typecasting, Karloff was grateful for it. “They tell me I’m typecast,” he said. “Well, I’ve been fortunate. Actors are extremely lucky to be typecast, like any tradesman who is known for specialization. It is a trademark, a means by which the public recognizes you. . . . The monster was, indeed, the best friend I could ever have.”

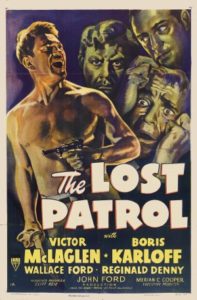

In the non-horror films—they may be hard to find, but he did make a few—he was equally versatile. Consider, again, the range between the religious fanatic in The Lost Patrol and the unjustly condemned prisoner in Devil’s Island.

Like Lugosi, though not to that extent, Karloff was sometimes undiscerning in the roles and films he undertook. Many of his non-horror films were ineptly written and directed, as were, indeed, many of his horror flicks. He was led into unrewarding projects, such as the five Mr. Wong pictures, about an oriental detective, poor efforts against Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, and was miscast as a friendly old man in Night Key (1937), where, admittedly, he was out of his depth.

The leading lady in The Black Cat, Julie Bishop, gives adequate support to her always attentive husband, played by an acting-by-the-numbers Manners, while, at the same time, never suggesting why he, or any man, would be particularly attracted to her. With a somewhat plain face, which doesn’t help matters, she wears the popular hair style of the ’30s—rigid, uniform waves that hug her head.

The leading lady in The Black Cat, Julie Bishop, gives adequate support to her always attentive husband, played by an acting-by-the-numbers Manners, while, at the same time, never suggesting why he, or any man, would be particularly attracted to her. With a somewhat plain face, which doesn’t help matters, she wears the popular hair style of the ’30s—rigid, uniform waves that hug her head.

Although never given roles to exploit what talent she had, Bishop is perhaps best remember as the girl waiting for her man to come home from the war—in Action in the North Atlantic and Sands of Iwo Jima. About half way through her life, she retired from movies and television to devote herself to painting and exhibiting her art. She died as recently as 2001.

American cinematographer John J. Mescall had shot such divergent films as The Bride of Frankenstein, the 1936 Showboat and The Bridge of San Luis Rey. And English art director Charles D. Hall had done sets for a quartet of early ’30s horrors: Dracula, Frankenstein, Murders in the Rue Morgue and The Invisible Man. Together, the two men, with Ulmer’s assisting in the art decoration, created for The Black Cat its eerie atmosphere and modernistic and, at the same time, unsettling sets, this house of steel and glass, with its unadorned, vacant walls.

Poelzig’s first appearance is quite effective and moody, his rising from his bed, where his wife sleeps, his silhouette moving across the curtains of a wide window. The centerpiece for the set for the satanic mass is a patriarchal cross—think of the American Lung Association symbol—lying on its side. From one of its nooks Poelzig delivers his chants. This set may remind viewers, for one, of those in The Son of Frankenstein, but they are by another Universal regular, Russell A. Gausman.

Poelzig’s first appearance is quite effective and moody, his rising from his bed, where his wife sleeps, his silhouette moving across the curtains of a wide window. The centerpiece for the set for the satanic mass is a patriarchal cross—think of the American Lung Association symbol—lying on its side. From one of its nooks Poelzig delivers his chants. This set may remind viewers, for one, of those in The Son of Frankenstein, but they are by another Universal regular, Russell A. Gausman.

As a perspective on the importance of the score in The Black Cat, there is to be remembered a similar precedent set by Max Steiner. In the 1933 King Kong, he created something of a milestone in movie history by composing one of the first continuous film scores, if not the first. Not only that, the music was all original. It was a salient event because, at that time, the only music a movie audience could usually hope to hear was that behind the opening titles and, if there were any, during the closing credits. When there was music, wherever it was, however much there was, it was more than likely recycled classical music. Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake was especially hackneyed among horror films, appearing in Dracula, The Mummy, et cetera.

Now enter The Black Cat a year after King Kong. Heinz Roemheld duly receives screen credit as music director. He is also, uncredited, the conductor of the orchestra, but not the composer of the music. There is no one composer; there are many composers, and almost continuous music is provided by the long dead. And good music it is, good in the sense that it is well matched to the happenings on screen, either from the standard or, occasionally, from the obscure literature of classical music.

Where to begin?! The main title opens with an eruptive bit of Liszt’s tone poem Tasso—just a fragmentary motif that will appear later in sinister moments. Immediately following this, the credits still rolling, a nondescript theme begins, gradually segueing into the love theme from Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Fantasy-Overture, with an occasional “changed” note. This anomalous tune will underline the romance of Joan and Peter.

According to what follows on screen, its temper and milieu, the appropriate already-written music is called forth for the occasion: The boarding of the Orient Express in the first scene, a Brahms Hungarian Dance. The two storms, the storm section from, again, a Liszt tone poem, Les Préludes. The appearance of the police, a snatch from Tchaikovsky’s March Slav. For dramatic moments—lovers in distress, say—either the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony or Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony. And for skulduggery, especially on Poelzig’s part, the slow movement of Schumann’s E-Flat Piano Quintet, minus the piano in Walter Schiller’s rescoring. Even Poelzig’s doorbell chimes—or maybe it “gongs”—the first four notes of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger Overture.

According to what follows on screen, its temper and milieu, the appropriate already-written music is called forth for the occasion: The boarding of the Orient Express in the first scene, a Brahms Hungarian Dance. The two storms, the storm section from, again, a Liszt tone poem, Les Préludes. The appearance of the police, a snatch from Tchaikovsky’s March Slav. For dramatic moments—lovers in distress, say—either the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony or Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony. And for skulduggery, especially on Poelzig’s part, the slow movement of Schumann’s E-Flat Piano Quintet, minus the piano in Walter Schiller’s rescoring. Even Poelzig’s doorbell chimes—or maybe it “gongs”—the first four notes of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger Overture.

Among both Internet movie website commentaries and professional critics—even the late astute Roger Ebert—the background scores in films are rarely mentioned, as if the music exists apart from the films, like a disposable appendage. Even Calvin Thomas Beck, in his Heroes of the Horrors, despite an unusually long critique of The Black Cat, which he calls “a landmark in the genre” and “the best of Universal’s “Golden Horror Films of the thirties,” fails to give even a nodding reference to the music.

Forget that the score in this instance isn’t original. That’s a small negative under the circumstances. The early years of sound was an era, by today’s standards, of primitive techniques and a kind of feeling-in-the-dark experimentation to create a new art in alien territory. A score as accomplished as that for The Black Cat, however unoriginal its origins, is responsible, in large part, for making the film what it is. Perhaps, even, that “landmark” Beck mentioned, though I would disagree that the film is the best of Universal’s ’30s horrors.

Forget that the score in this instance isn’t original. That’s a small negative under the circumstances. The early years of sound was an era, by today’s standards, of primitive techniques and a kind of feeling-in-the-dark experimentation to create a new art in alien territory. A score as accomplished as that for The Black Cat, however unoriginal its origins, is responsible, in large part, for making the film what it is. Perhaps, even, that “landmark” Beck mentioned, though I would disagree that the film is the best of Universal’s ’30s horrors.