“All you need to start an asylum is an empty room and the right kind of people.” — Alexander Bullock

The setting of My Man Godfrey, released in September of 1936, was Depression-era United States. For many at the time, the film, comedy though it is, had a painfully personal relevance, as it still does—undoubtedly even more germane now—with the overly rich enjoying life, partying, dining and cavorting, while the poor and destitute, then and now, exist as nonentities. Out of sight, or even within sight—either way—out of mind.

Although President Franklin Roosevelt’s measures for putting the country back on its feet made a strong beginning, 1933-1936, a downturn was coming in 1937. Neither the better times of the ’30s—times were never really “good”—nor that near-return to the dark days of 1932-33 would deprive the movie of its biting relevance, seething beneath all the surface humor.

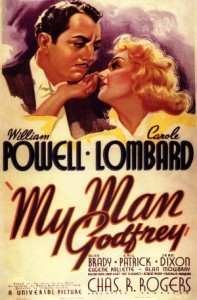

One of the best and best-remembered films of the ’30s, My Man Godfrey throws together in brilliant proximity two of the era’s favorite stars, the urbane, usually detective-playing (Philo Vance, Nick Charles, etc.) William Powell and the zany, sometimes sophisticated (Jane Mason, Hazel Flagg, etc.) Carole Lombard. For the mirth and merriment, they are joined by a cast of what was then—and still are to us aficionados—familiar faces.

The main title is most unusual, even now: the camera pans across an animated New York skyline at night, with the title and all the credits given in neon lights, on billboards, across buildings, the stars’ names shown twice, all accompanied by lively dance music of the period. Ideally suited for black and white, the graphics dissolve into reality, the silhouette of a Hoovervillle, with smoke drifting up from some derelict’s evening fire. Shot from below a rubbish pile, a swanky car arrives and two ladies in evening dress alight.

Seems that the New York idle rich are on a scavenger hunt, a game in vogue at the time, and not far down the list of “unwanted” things to find is an example of that era’s “forgotten man.” Two sisters of the Bullock family, Irene (Lombard) and Cornelia (Gail Patrick), have found, in a city dump, such an itinerant (Powell). Annoyed and insulted by the arrogant Cornelia’s request to borrow him for her list —“Do you want the five dollars or don’t you?” she asks when he quizzes her—the bearded man pushes her into an ash pile.

Seems that the New York idle rich are on a scavenger hunt, a game in vogue at the time, and not far down the list of “unwanted” things to find is an example of that era’s “forgotten man.” Two sisters of the Bullock family, Irene (Lombard) and Cornelia (Gail Patrick), have found, in a city dump, such an itinerant (Powell). Annoyed and insulted by the arrogant Cornelia’s request to borrow him for her list —“Do you want the five dollars or don’t you?” she asks when he quizzes her—the bearded man pushes her into an ash pile.

Irene approaches him with the same request, but with admitted trepidation, as she has seen what he did to her sister. To him, Irene seems a little nicer and he agrees to go with her to the party’s headquarters at the Waldorf Ritz, partly because in doing so, as Irene explains, she’ll beat Cornelia.

Accepting an offer from Irene to “buttle” for the Bullocks, Godfrey—that’s his name—is introduced to the eccentric, daffy family, all idle and, seemingly, frivolous—except one. In the indolent category are the mother Angelica (Alice Brady), who sees pixies in the mornings after her hangovers, the snotty Cornelia, who asks the new butler to clean something off her shoe, and Irene, who announces that Godfrey is to become her protégé, much as mother has Carlo (Mischa Auer) as her protégé.

Accepting an offer from Irene to “buttle” for the Bullocks, Godfrey—that’s his name—is introduced to the eccentric, daffy family, all idle and, seemingly, frivolous—except one. In the indolent category are the mother Angelica (Alice Brady), who sees pixies in the mornings after her hangovers, the snotty Cornelia, who asks the new butler to clean something off her shoe, and Irene, who announces that Godfrey is to become her protégé, much as mother has Carlo (Mischa Auer) as her protégé.

Carlo is a hanger-on loafer, feigning intellectualism, reading prose and singing Russian songs at the piano—and always ready for the d’oeuvres when Godfrey passes among the lounging family with a tray. Auer is best remembered in My Man Godfrey for his gorilla imitation, grunting, hopping over the furniture and scratching his sides.

The one character who has managed to keep his sanity, or at least most of it, and who is in charge of this menagerie, or so he believes, is the husband of the “dizzy old gal,” Alexander Bullock (Eugene Pallette). Calling the family to order at one point to complain about the mounting bills, forgetting for the moment the horse which Irene rode home from the scavenger hunt, he announces: “I find that you people have confused me with the Treasury Department.”

The one character who has managed to keep his sanity, or at least most of it, and who is in charge of this menagerie, or so he believes, is the husband of the “dizzy old gal,” Alexander Bullock (Eugene Pallette). Calling the family to order at one point to complain about the mounting bills, forgetting for the moment the horse which Irene rode home from the scavenger hunt, he announces: “I find that you people have confused me with the Treasury Department.”

Since Cornelia cannot seduce, or even make a friend of, Godfrey, she attempts to frame him with a well-planted pearl necklace, which, when the police arrive, has inexplicably disappeared. Godfrey, taking pity on beleaguered Mr. Bullock, invests the pearls and turns the earnings over to him.

The movie alternates between romantic, touching scenes and slapstick antics. In the first case, Godfrey and Irene wash and dry dishes together and he tells her that it’s time he was moving on. As for the second, when Irene fakes a fainting spell, Godfrey carries her to the shower and turns on the water, a drenching she interprets as the final sign that he loves her.

There are dramatic scenes, as the one where Godfrey tells Cornelia exactly what he thinks of her: “You belong to that unfortunate category that I would call the ‘Park Avenue brat,’ a spoiled child who’s grown up in ease and luxury, who’s always had her own way and whose misdirected energies are so childish that they hardly deserve the comment, even of a butler on his off Thursday.”

There are dramatic scenes, as the one where Godfrey tells Cornelia exactly what he thinks of her: “You belong to that unfortunate category that I would call the ‘Park Avenue brat,’ a spoiled child who’s grown up in ease and luxury, who’s always had her own way and whose misdirected energies are so childish that they hardly deserve the comment, even of a butler on his off Thursday.”

Some of the other cast members include Jean Dixon as Molly the maid, also smitten with Godfrey, and Robert Light, who discovers at a party, rather suddenly, that he is Irene’s fiancé, her impulsive prank to incite Godfrey’s interest. Alan Mowbray is Tommy Gray from Godfrey’s upper crust past. As the scorekeeper for the scavenger hunters, Franklin Pangborn makes as representative an appearance here as in any of his over two hundred films, all with fleeting roles. Look quickly for Jane Wyman at the party.

Behind the camera, Gregory La Cava produced and directed, and the few bits of music are by Charles Previn. The film is based on Eric Hatch’s novel; he also headed the team of screenwriters. And the cinematographer is Ted Tetzlaff, who, if he had done nothing else, photographed Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious with compelling elegance.