For a moment, he forgets he’s a thief—and she forgets she’s a lady!

For a moment, he forgets he’s a thief—and she forgets she’s a lady!

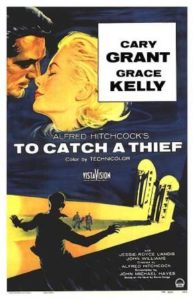

Warner Brothers has just released a new tribute to Grace Kelly, a box set of some of her best films. It’s understandable that two contributions should come from Alfred Hitchcock, of the three features she made for him, all in a row in 1954 and 1955. The first film was Dial M for Murder with Ray Milland, the second Rear Window with James Stewart and the last To Catch a Thief with Cary Grant.

The inclusion of both Dial M for Murder and To Catch a Thief in the Warners set seems not only wise but logical, since some of Grace’s best acting occurs in her Hitchcock films. She demonstrates a wider range here than usual for an actress who really didn’t infuse many of her performances with that much depth. She responded to Hitch’s direction, however, as she responded to no other director’s. “I learned a tremendous amount about motion-picture making,” she said. “He gave me a great deal of confidence in myself.” He was obviously more helpful toward Grace than toward Ingrid Bergman, who wrote in her autobiography, My Story, that when she complained about what she thought an awkward line, Hitch simply advised, “If you can’t do it my way, fake it.”

Rear Window may be Grace’s best performance, period, even beyond her Oscar win for The Country Girl (also included in this WB set), where she plays, against her image, a plain Jane and wife of an alcoholic husband (Bing Crosby). But she was never lovelier than as a man-hunting seductress in To Catch a Thief. Her high moment of glamour occurs in the climax of the film, a masquerade ball where she appears in a golden gown, designed by Edit Head.

Blake Edwards must have retained the ball sequence in his memory when he directed a similar scene in The Pink Panther, the first of the Peter Sellers movies in that series, and added further the fireworks from another scene in Thief.

To Catch a Thief is an atypical Hitchcock film—not the usual psychological thriller, though, as in all his films, dark motifs and symbolism do lurk beneath the surface, if here more subtly. It’s really a sophisticated whodunit in all but name, maybe, even, a high-class travelogue. It was something of a “vacation” movie, as much for Hitch as for cast and crew, who seemed to have gotten along famously. Since his screenwriter had never been to the French Riviera, Hitchcock sent John Michael Hayes (and his wife) there at studio expense to research the locales.

To Catch a Thief is an atypical Hitchcock film—not the usual psychological thriller, though, as in all his films, dark motifs and symbolism do lurk beneath the surface, if here more subtly. It’s really a sophisticated whodunit in all but name, maybe, even, a high-class travelogue. It was something of a “vacation” movie, as much for Hitch as for cast and crew, who seemed to have gotten along famously. Since his screenwriter had never been to the French Riviera, Hitchcock sent John Michael Hayes (and his wife) there at studio expense to research the locales.

In many respects the Riviera, mainly at Côte d’Azur, is the star of this movie. Much of the splendid seacoast photography, including—in a Hitch film?—a car chase (!), is the work of second unit director Herbert Coleman. Main cinematographer Robert Burks won his only Oscar, for Best Color Cinematography; two of his three other nominations were also for Hitchcock films, Strangers on a Train and Rear Window. His association with the director ended with Marnie and his death in 1968.

To Catch a Thief was Hitchcock’s first motion picture in Paramount’s new VistaVision, a screen process some critics, including Peter Bogdanovich, proclaim superior to all others, though in the projection process VistaVision proved cumbersome and expensive, and was discontinued around 1961. While its trademark sharpness and clarity are evident in many scenes, Hitch failed to take full advantage of its merits, shortcomings later largely rectified in North by Northwest.

To Catch a Thief was Hitchcock’s first motion picture in Paramount’s new VistaVision, a screen process some critics, including Peter Bogdanovich, proclaim superior to all others, though in the projection process VistaVision proved cumbersome and expensive, and was discontinued around 1961. While its trademark sharpness and clarity are evident in many scenes, Hitch failed to take full advantage of its merits, shortcomings later largely rectified in North by Northwest.

Hitch’s continued love of rear screen projection, often obvious in Thief, would become, some say, an intentional self-parody in Marnie, or else the result of laziness or indifference; or, as Hitch biographer Donald Spoto has written, that “these aberrations were deliberate on Hitchcock’s part, a conscious reversion to an expressionistic style that used artifice to represent a disordered psyche.”

In Thief, the process is obvious, for starters, in Grant and Kelly’s roadster picnic, which almost jarringly switches between on-location medium shots of car and the actual seascape beyond and tight studio close-ups. The flat, over-bright, almost shadowless light in the studio work is even more obvious in the scenes between Grant and Brigitte Auber at the floating dock, where, further, the multiple and unnatural reflections on the water obviously come from studio lights rather than the sun.

In Thief, the process is obvious, for starters, in Grant and Kelly’s roadster picnic, which almost jarringly switches between on-location medium shots of car and the actual seascape beyond and tight studio close-ups. The flat, over-bright, almost shadowless light in the studio work is even more obvious in the scenes between Grant and Brigitte Auber at the floating dock, where, further, the multiple and unnatural reflections on the water obviously come from studio lights rather than the sun.

In keeping with the lightness of the film, the plot of Thief is one of Hitch’s most uncomplicated. John Robie (Grant) is an ex-jewel thief, once known as “The Cat,” but now quietly tending his vineyards. “I haven’t stolen jewelry in fifteen years,” he tells the police when he’s a suspect in a series of robberies in the area. Robie eludes the police and finds refuge with his World War II French Resistance buddies and with old girlfriend, Danielle (Auber).

He clearly sees that someone is using his modus operandi and seeks the help of insurance agent H. H. Hughson (John Williams), hoping to catch the real cat burglar in the act. Hughson suggests that around the tourist resorts there are possible suspects among the rich who flaunt their jewels. They include Jessie Stevens (Jessie Royce Landis, who, in North by Northwest, would, only eight years older, play Grant’s mother) and her husband-hunting daughter Frances (Kelly).

Although Frances at first assumes Robie is the burglar in question and is game to play along, she is fascinated by his charms. They have a picnic of chicken in her parked roadster along a coast road, the first of two famous scenes involving sexual puns and double entendres. “Do you want a leg or a breast?” she asks him. “You make the choice,” Robie replies. “Tell me,” she resumes, “how long has it been?” “Since what?” “Since you were in America last.” (In The Horse Soldiers [1959], when Constance Towers, in her low-neck dress, offers John Wayne a similar choice from a platter of chicken, he replies that he’s had plenty of both. Had director John Ford seen To Catch a Thief?)

Although Frances at first assumes Robie is the burglar in question and is game to play along, she is fascinated by his charms. They have a picnic of chicken in her parked roadster along a coast road, the first of two famous scenes involving sexual puns and double entendres. “Do you want a leg or a breast?” she asks him. “You make the choice,” Robie replies. “Tell me,” she resumes, “how long has it been?” “Since what?” “Since you were in America last.” (In The Horse Soldiers [1959], when Constance Towers, in her low-neck dress, offers John Wayne a similar choice from a platter of chicken, he replies that he’s had plenty of both. Had director John Ford seen To Catch a Thief?)

Hitch certainly felt the second such scene was the pièce de résistance of Thief, one he had planned with understandable relish. He sat within three feet of Grant and Kelly during the close-up shots, almost as if to become part of a threesome. To create the greatest possible emphasis, nighttime shots of a fireworks display are tightly intercut between lines as the two actors sit close together on a sofa.

“I have a feeling,” Frances says, moving closer to him in her strapless, low-cut gown and wearing a brilliant necklace, “that tonight you’re going to see one of the Riviera’s most fascinating sights. I’m talking about the fireworks, of course. . . . Even in this light I can tell where your eyes are looking. Look. Hold them . . . diamonds! The only thing in the world you can’t resist. Then tell me you don’t know what I’m talking about. Ever had a better offer in your whole life? One with everything! . . . ”

“I have a feeling,” Frances says, moving closer to him in her strapless, low-cut gown and wearing a brilliant necklace, “that tonight you’re going to see one of the Riviera’s most fascinating sights. I’m talking about the fireworks, of course. . . . Even in this light I can tell where your eyes are looking. Look. Hold them . . . diamonds! The only thing in the world you can’t resist. Then tell me you don’t know what I’m talking about. Ever had a better offer in your whole life? One with everything! . . . ”

“I’ve never had a crazier one,” Robie replies.

“Just as long as you’re satisfied.”

“You know just as well as I do this necklace is imitation.”

“Well, I’m not!”

Robie thinks the cat burglar will strike again and sets a trap at a gala masquerade ball. With the police and Hughson disguised among the guests, Frances is dressed in her golden gown and Robie is hidden behind the mask of a Moor. Sometime during the evening Hughson assumes Robie’s costume, while Robie slips off to the roof, lying in wait for the expected burglar. He soon appears, jewels in hand—or, rather, she appears, because it’s Danielle. When she almost falls off the roof, Robie grabs her arm, forcing her to confess to being the thief.

Robie thinks the cat burglar will strike again and sets a trap at a gala masquerade ball. With the police and Hughson disguised among the guests, Frances is dressed in her golden gown and Robie is hidden behind the mask of a Moor. Sometime during the evening Hughson assumes Robie’s costume, while Robie slips off to the roof, lying in wait for the expected burglar. He soon appears, jewels in hand—or, rather, she appears, because it’s Danielle. When she almost falls off the roof, Robie grabs her arm, forcing her to confess to being the thief.

Mystery solved, Robie returns to his vineyard, but Frances follows him and persuades him that she’s the woman for him, though he, in agreeing, seems somewhat edgy that she plans to include her mother.

To Catch a Thief is Alfred Hitchcock’s first light film since 1941’s Mr. and Mrs. Smith, made then only because Carole Lombard suggested it. Thief would be immediately succeeded by more humor, now macabre and maudlin, in the farce The Trouble with Harry, about a reappearing body that won’t go away. Except for North by Northwest, Hitch’s subsequent films would become darker and darker and would, more and more, reflect his fears and psychoses, reaching a true sadistic rage in Frenzy. His following movie five years later—the longest gap between any two Hitch films—would be a redemption of sorts, the jovial, unfussy Family Plot in 1976. Then finis to his career, and, four years later, to his life.

Hitch had planned Grace’s next film to be Marnie, eventually released in 1964, but Tippi Hedren would be a poor substitute when Grace went off to become Princess of Monaco. Before her marriage to Prince Rainier, though, she would make two more films. In the first, The Swan, a portent of her royal life to come, she plays a princess pursued by an unappealing prospective husband, Alec Guinness. The second movie, High Society, also included in this new WB DVD set, would offer the actress a screen choice, this time from among three men—Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra or John Lund.

Hitch had planned Grace’s next film to be Marnie, eventually released in 1964, but Tippi Hedren would be a poor substitute when Grace went off to become Princess of Monaco. Before her marriage to Prince Rainier, though, she would make two more films. In the first, The Swan, a portent of her royal life to come, she plays a princess pursued by an unappealing prospective husband, Alec Guinness. The second movie, High Society, also included in this new WB DVD set, would offer the actress a screen choice, this time from among three men—Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra or John Lund.

Note: Although referenced here, no review copy or other consideration was provided by Warner Brothers.