Remember: A world without string is chaos.

Remember: A world without string is chaos.

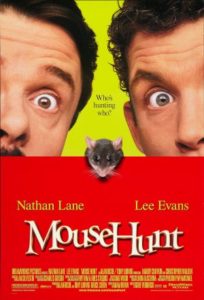

The setup is simple—two not-so-bright brothers inherit a rundown string factory and an old mansion. The essential element of conflict, so important both in drama and comedy, is pretty basic here—an enterprising rodent intent on frustrating the brothers’ occupancy of the house. The humor, if juvenile and more in the style of a live-action cartoon, will not be to everyone’s taste, but for those who welcome an escape from life’s unpleasant aspects and aren’t too disturbed by the ridiculous, Mouse Hunt will provide a side-splitter par excellence.

For what it is, maybe despite that, the film is handsomely crafted and presented. First, Nathan Lane and British-born Lee Evans, though he affects a convincing American accent, provide Laurel-and-Hardy-type key performances. Ably supporting them are Christopher Walken in another eccentric, over-the-top role and William Hickey and Eric Christmas in their final screen appearances. At the end of Mouse Hunt, before the final credits roll, appears a dedication to the memory of Hickey, who died that year.

In quite a contrast to his lumbering and unfocused direction of three of the Pirates of the Caribbean films, Gore Verbinski sets a wild, frantic pace throughout, in this, his first full-length feature movie, and the first family comedy from DreamWorks Pictures. He provides little time for a viewer to consider if any of the antics make sense, before the next explosion, rocket blast, staircase crunch, drowning or shotgun discharge. And the fun of it is that it doesn’t matter whether it all makes sense of not.

Cinematographer Phedon Papamichael works in madcap tandem with the director, and seems to share the same sense of fun—and, yes, the ridiculous. Maybe both are men who have never grown up and receive glee from such a childlike, not childish, scenario. With considerably more films to his credit than Verbinski, Papamichael’s award-winning movies include the 3:10 to Yuma remake, The Million Dollar Hotel, the black-and-white Nebraska and The Weatherman, directed by friend Verbinski.

Cinematographer Phedon Papamichael works in madcap tandem with the director, and seems to share the same sense of fun—and, yes, the ridiculous. Maybe both are men who have never grown up and receive glee from such a childlike, not childish, scenario. With considerably more films to his credit than Verbinski, Papamichael’s award-winning movies include the 3:10 to Yuma remake, The Million Dollar Hotel, the black-and-white Nebraska and The Weatherman, directed by friend Verbinski.

Like Verbinski and Papamichael, Adam Rifkin, the author of the Mouse Hunt screenplay, was born in the mid-’60s. And like his fellow artists and as a writer himself of other comedies such as Underdog, Without Charlie and The Chase, he might also possess a hidden, or maybe not so hidden, childlike delight for the fanciful, the outlandish, the irreverent.

And then there is the score by Alan Silvestri. One of the older veterans who contributes to the film, born in 1950, his career dates to 1972 and The Doberman Gang. After a brief stint in television following his first four films, since 1984 Silvestri has almost exclusively devoted his talents to scoring motion pictures—the best known probably the Back to the Future series, Forest Gump and Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which combines cartoon characters with live action.

And then there is the score by Alan Silvestri. One of the older veterans who contributes to the film, born in 1950, his career dates to 1972 and The Doberman Gang. After a brief stint in television following his first four films, since 1984 Silvestri has almost exclusively devoted his talents to scoring motion pictures—the best known probably the Back to the Future series, Forest Gump and Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which combines cartoon characters with live action.

Since the Mouse Hunt mouse, seen in various forms as puppet, computer creation or real, is the star of the show, Silvestri’s score is dominated by its (“his”?) theme. It’s an appropriately scurrying melody, introduced in the inventive opening credits which show the process of string making, with finished balls of twine dropping from the machine. Aside from the borrowed themes, including “We’re In the Money” and Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Artist’s Life, the score is actually an ingenious set of variations on the mouse theme. Sometimes Silvestri slips, intentionally or subliminally, into a quasi-Prokofiev bit of dissonant complexity or a march in homage to John Williams. Or when the brothers face the worst of terrors, the composer paints, quite differently, a cloud of cold, ominous reality worthy of the darkest, most serious drama.

If there’s been any doubt, despite the jauntiness of the main title, that this is a comedy, it is quickly dispelled by the tone of the funeral that opens the film. In a downpour, on the stairway entrance of a church, a cluster of mourners make room for the pallbearers descending with the casket. Leading the way, one on either side, are two brothers, sons of the deceased, arguing over the color of one of their suits. They slip, the casket slides down the stairs and its occupant is hurled skyward, falling back to earth through an open manhole, à la the Roadrunner. So much for pop, eh? And so much for the thought that this could be anything but a comedy.

If there’s been any doubt, despite the jauntiness of the main title, that this is a comedy, it is quickly dispelled by the tone of the funeral that opens the film. In a downpour, on the stairway entrance of a church, a cluster of mourners make room for the pallbearers descending with the casket. Leading the way, one on either side, are two brothers, sons of the deceased, arguing over the color of one of their suits. They slip, the casket slides down the stairs and its occupant is hurled skyward, falling back to earth through an open manhole, à la the Roadrunner. So much for pop, eh? And so much for the thought that this could be anything but a comedy.

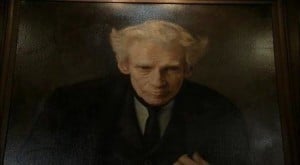

Rudolph Smuntz (Hickey) is the deceased father, and on the wall of the factory office is his portrait, which changes expression throughout the movie according to his sons’ varying behavior. The two sons, Ernie (Lane) and Lars (Evans), listen to the reading of the will from the lawyer (Christmas). To begin, there is a ceramic egg, a half box of Cuban cigars and a handful of spoons. Other than that, there is a “broken down string factory,” as Ernie calls it, and a dilapidated old house. “Spoons! Spoons!” Ernie cries sarcastically, fingering the utensils. “So many spoons—and so little time.” In the same mocking vein, he suggests Lars should have the egg, which Lars immediately breaks.

Rudolph Smuntz (Hickey) is the deceased father, and on the wall of the factory office is his portrait, which changes expression throughout the movie according to his sons’ varying behavior. The two sons, Ernie (Lane) and Lars (Evans), listen to the reading of the will from the lawyer (Christmas). To begin, there is a ceramic egg, a half box of Cuban cigars and a handful of spoons. Other than that, there is a “broken down string factory,” as Ernie calls it, and a dilapidated old house. “Spoons! Spoons!” Ernie cries sarcastically, fingering the utensils. “So many spoons—and so little time.” In the same mocking vein, he suggests Lars should have the egg, which Lars immediately breaks.

Ernie has no time for the will or anything else. He’s off to his upscale restaurant to serve the town’s mayor (Cliff Emmich) his “Duck a l’Orange avec du quack sauce,” flamboyantly announced in a fake French accent. Although Mayor McKrinle is grossly overweight, his stomach apparently hasn’t room for the cockroach which crawls out of father’s old box of cigars that Ernie appropriated for himself. The mayor promptly dies from a heart attack or two, and the board of health closes the restaurant.

Meanwhile, while Lars is considering an offer from some obvious criminals to buy the factory, he pulls a piece of string from his pocket and has a flashback—to the deathbed of his father. Rudolph passes to him the string he had kept in his pocket for sixty years, asking his two sons to share it and to promise never to sell the factory. When Lars refuses to sell the factory, his greedy wife (Vicki Lewis) throws him out of the house.

Meanwhile, while Lars is considering an offer from some obvious criminals to buy the factory, he pulls a piece of string from his pocket and has a flashback—to the deathbed of his father. Rudolph passes to him the string he had kept in his pocket for sixty years, asking his two sons to share it and to promise never to sell the factory. When Lars refuses to sell the factory, his greedy wife (Vicki Lewis) throws him out of the house.

Now both brothers, without either jobs or homes, are forced to live in the old mansion. (As their car approaches the house through a snow-covered landscape, Silvestri’s orchestra settles into a soft, sentimental version of “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.” Judging by the cars, clothes and general décors, the time is Christmas, sometime in the late 1930s, early ’40s.)

That first night, sharing an old iron bed, the two men sense they are not alone. There are unexplained noises. Shining a flashlight, they are startled by a creature-like shadow, which turns out to be only a child’s jack-in-the-box. So—all is well. Or is it? In trying to lift Ernie up to the ledge to the toy, Lars boosts him too high and his head bursts through the ceiling. Not bad, because in the attic Ernie sees scrolls of paper, which will soon prove significant; not good, either, because he sees . . . a mouse. “It’s only a mouse,” he calls down to Lars. “Only” a mouse? . . .

That first night, sharing an old iron bed, the two men sense they are not alone. There are unexplained noises. Shining a flashlight, they are startled by a creature-like shadow, which turns out to be only a child’s jack-in-the-box. So—all is well. Or is it? In trying to lift Ernie up to the ledge to the toy, Lars boosts him too high and his head bursts through the ceiling. Not bad, because in the attic Ernie sees scrolls of paper, which will soon prove significant; not good, either, because he sees . . . a mouse. “It’s only a mouse,” he calls down to Lars. “Only” a mouse? . . .

The scrolls are blueprints from 1876 of this monstrosity of a house, designed by the famous architect Charles Lyle LaRue. This causes quite a stir among the clique of LaRue connoisseurs, especially one collector, Alexander Falko (Maury Chaykin), who makes a highly respectable offer. Believing he can make more money after a restoration and auction, Ernie rejects the offer.

First on the list of “restoration” is annihilating the mouse. Easier said than done. A first assault with a power nail driver, with the little mouse fleeing behind the walls—and surviving—is ineffective; and, beyond this, earns for the mouse some sympathy from the less bloodthirsty members of the audience.

Then, after the brothers have covered the entire floor with mouse traps, and walled themselves into a corner, the mouse climbs to a top shelf, dives onto a spoon, which flips a cherry into the air. The cherry falls to the floor, rolls around and, after teetering, its stem slowly, slowly descends to ever-so-lightly tap the bait on a trap, setting off all the other traps and ensnarling the two aggressors in their own traps.

Then, after the brothers have covered the entire floor with mouse traps, and walled themselves into a corner, the mouse climbs to a top shelf, dives onto a spoon, which flips a cherry into the air. The cherry falls to the floor, rolls around and, after teetering, its stem slowly, slowly descends to ever-so-lightly tap the bait on a trap, setting off all the other traps and ensnarling the two aggressors in their own traps.

Next, Ernie jams a vacuum cleaner nozzle into the mouse hole with the intent of sucking up the little nuisance. When the nozzle accidentally breaks into the sewer line and its ever-expanding dust bag explodes disastrously, the brothers resort to a ferocious cat from the city pound. “Catzilla,” however, proves no more successful. He and the mouse have a frantic chase about the house, at one point over the keys and inside a piano, with a rippling keyboard, right out of a Tom and Jerry cartoon. The cat—whose rendering is perhaps the only weak point in the film’s superb special effects—ends up in a dumbwaiter; the mouse chews through the supporting rope and down goes the cat—crash, in a cloud of dust!—never to be seen again.

Ernie and Lars then hire Caesar (Walken), an over-technical, gadget-minded exterminator. “You have to get inside their mind. You have to think . . . like a mouse,” he philosophizes. When Caesar has crawled his way through the house, tethered to a cable from the winch on his truck, the mouse releases the restraint lever and the would-be rodent killer is dragged back though the house, splitting the staircase down the middle, and back to his truck. When the paramedics come for him, he is incoherent.

Ernie and Lars then hire Caesar (Walken), an over-technical, gadget-minded exterminator. “You have to get inside their mind. You have to think . . . like a mouse,” he philosophizes. When Caesar has crawled his way through the house, tethered to a cable from the winch on his truck, the mouse releases the restraint lever and the would-be rodent killer is dragged back though the house, splitting the staircase down the middle, and back to his truck. When the paramedics come for him, he is incoherent.

During an argument, Lars throws an orange at Ernie and accidentally knocks out the mouse with a direct hit. Unable to kill their adversary, they put the rodent in a box—without air holes—and mail it to Fidel Castro in Cuba. Time has apparently moved into the ’60s.

Feeling safe without the mouse and the house finally renovated, Ernie holds his auction, attended by a variety of millionaires and aficionados of LaRue architecture. Falko offers him $10 million to call off the sale, but Ernie refuses. He’s sure he can make more. The auction has reached a $25 million bid. In the meantime, the brothers have discovered that the mouse is back—the empty box, with a hole in it, was returned from Cuba, postage due. In another assault, they fill the walls of the house with water from a garden hose. The end result is predictable: the walls burst, the audience is washed outside in a great flood and the house, the exquisite LaRue molding and all, collapses.

Feeling safe without the mouse and the house finally renovated, Ernie holds his auction, attended by a variety of millionaires and aficionados of LaRue architecture. Falko offers him $10 million to call off the sale, but Ernie refuses. He’s sure he can make more. The auction has reached a $25 million bid. In the meantime, the brothers have discovered that the mouse is back—the empty box, with a hole in it, was returned from Cuba, postage due. In another assault, they fill the walls of the house with water from a garden hose. The end result is predictable: the walls burst, the audience is washed outside in a great flood and the house, the exquisite LaRue molding and all, collapses.

Yes, the mouse must’ve drown—surely. Yes, surely.

Now homeless, Ernie and Lars return to the factory, the mouse—yes, the mouse!—traveling with them on the undercarriage of their car. When the brothers awaken next morning, they hear the sounds of the factory. In operation again?! The mouse has restructured the assembly line, so that instead of producing balls of twine, it now produces balls of cheese.

Now homeless, Ernie and Lars return to the factory, the mouse—yes, the mouse!—traveling with them on the undercarriage of their car. When the brothers awaken next morning, they hear the sounds of the factory. In operation again?! The mouse has restructured the assembly line, so that instead of producing balls of twine, it now produces balls of cheese.

In the final scene, the brothers have converted the factory into making novelty cheese. The mouse is in charge of quality control, sitting on Ernie’s shoulder and passing on the worth of new cheese flavors given him to sample. The portrait of Rudolph, now smiling its approval, is adjacent to the father’s framed piece of beloved string and the motto, “A world without string is chaos.”