“Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night may become a wolf when the wolf bane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.”

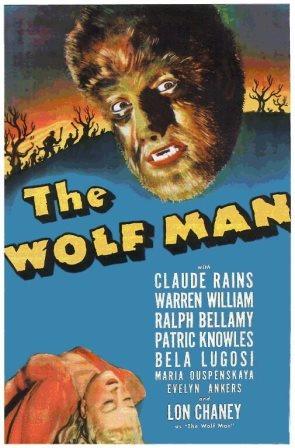

Much of the folklore—“wolflore,” wives tales?—known about werewolves and the process of their transformation, lycanthropy, originated in The Wolf Man. If any one watching this 1941 film is unfamiliar with the werewolf legend, a number of the characters quote the above line, ad nauseam, as a reminder.

The first of these signposts mentioned in the film is the pentagram as a sign of the werewolf, engraved on the handle of a most important cane. Another myth perpetuates the idea that this wild canine metamorphosis occurs during a full moon. The old gypsy woman of the movie initiates the idea that a werewolf can be killed with a silver bullet, a silver knife or, as demonstrated at least twice in the film, that cane with its silver handle. Introduced last, and to quote the old gypsy herself, “Whoever is bitten by a werewolf and lives becomes a werewolf himself.”

Unusual for this early in his career, Claude Rains has a non-villainous role here, remaining aloof from this werewolf business and denying that his son, played by Lon Chaney, Jr., has had the “wolf experience.” He began his career, however, playing disagreeable fellows. His first film, The Invisible Man in 1933, is one of the best in the horror genre. While it wisely mixes some diverting humor with the horror, The Wolf Man takes it all seriously.

The following year, Rains goes insane in The Man Who Reclaimed His Head, and, in 1935, he becomes an opium addict in The Mystery of Edwin Drood, a choirmaster who murders all suitors of his inamorata and buries them in the cathedral crypt. Next, as aristocrat Don Luis, a gout-crippled husband in Anthony Adverse (1936), he kills his wife’s lover in a duel. From eighteenth-century Italy to medieval England Rains lusts for power, first as the Earl of Hertford in The Prince and the Pauper (1937) and then as Prince John in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), both opposite Errol Flynn.

The following year, Rains goes insane in The Man Who Reclaimed His Head, and, in 1935, he becomes an opium addict in The Mystery of Edwin Drood, a choirmaster who murders all suitors of his inamorata and buries them in the cathedral crypt. Next, as aristocrat Don Luis, a gout-crippled husband in Anthony Adverse (1936), he kills his wife’s lover in a duel. From eighteenth-century Italy to medieval England Rains lusts for power, first as the Earl of Hertford in The Prince and the Pauper (1937) and then as Prince John in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), both opposite Errol Flynn.

When The Wolf Man opens, Larry Talbot (Chaney) is returning to his father’s ancestral home (a detailed matte painting) after eighteen years away. The death of his brother in a hunting accident has reunited him with his father, Sir John (Rains), after years of estrangement.

After Larry has met his father’s friend, Colonel Montford (Ralph Bellamy), chief constable of the district, he visits an antique store. He flatters a young woman, Gwen Conliffe (Evelyn Ankers), but she appears impassive. She, however, sells him a silver-handled walking stick, with an engraved pentagram and wolf’s head. She acquaints him with the werewolf legend and the “Even a man . . . ” quote. Despite her indifference, he says he will meet her at the shop that night and take her to the gypsy carnival that has just arrived in town.

After Larry has met his father’s friend, Colonel Montford (Ralph Bellamy), chief constable of the district, he visits an antique store. He flatters a young woman, Gwen Conliffe (Evelyn Ankers), but she appears impassive. She, however, sells him a silver-handled walking stick, with an engraved pentagram and wolf’s head. She acquaints him with the werewolf legend and the “Even a man . . . ” quote. Despite her indifference, he says he will meet her at the shop that night and take her to the gypsy carnival that has just arrived in town.

After a brief scene at home where his father quotes the “Even a man . . . ” line, Larry returns that evening to the antique store. Strangely enough, Gwen is waiting and introduces her friend Jenny (Fay Helm), who also quotes the line.

A fortuneteller, Bela (Bela Lugosi), reads Jenny’s palm and sees a pentagram, a portent of evil. “Go quickly! Go!” he says. As she runs through the foggy woods, she is attacked by a wolf, which Larry kills with his cane but not before he is bitten on the chest. Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya), another gypsy fortuneteller, happens by in her cart, greatly distressed over Larry’s wolf encounter. Unfortunately he leaves his cane.

Psychiatrist Dr. Lloyd (Warren William) and the police find beside the dead Jenny the body of Bela, but where is the wolf that Larry killed? (As Maleva will later explain, Bela was a werewolf and, upon death, returned to human form.)

Psychiatrist Dr. Lloyd (Warren William) and the police find beside the dead Jenny the body of Bela, but where is the wolf that Larry killed? (As Maleva will later explain, Bela was a werewolf and, upon death, returned to human form.)

During another visit to the carnival, Gwen is accompanied by her fiancé, Frank (Patric Knowles). In reading Larry’s fortune, Maleva sees the worst and gives him a protective pentagram pendant, which he later will give to Gwen “just in case.” For a reason unexplained, the pentagram, a sign of the werewolf, now becomes protection against one.

Larry goes home, notices the pentagram sign on his chest and sees his feet growing hair (no facial shots are used). Now transformed into a wolf, he tiptoes through the fog-drenched woods—what has tiptoeing to do with a wolf?

Next morning, Larry has no memory of killing a gravedigger (Tom Stevenson), but awakens to see muddy paw tracks on the carpet and windowsill. He at least has enough sense of guilt to rub them out.

Though still denying any wolf connection with his son, Sir John interprets the werewolf legend as a parable of “the good and evil in every man’s soul,” that “anything can happen to any man in his own mind.” Despite Larry’s cane being found beside Bela’s body, Dr. Lloyd lays on the psychiatric jargon, attributing any of Larry’s werewolf links to his own “psychic maladjustment.”

Though still denying any wolf connection with his son, Sir John interprets the werewolf legend as a parable of “the good and evil in every man’s soul,” that “anything can happen to any man in his own mind.” Despite Larry’s cane being found beside Bela’s body, Dr. Lloyd lays on the psychiatric jargon, attributing any of Larry’s werewolf links to his own “psychic maladjustment.”

On another nightly prowl as a wolf, Larry gets his foot caught in one of the traps which Frank and the colonel have set. By the time Larry has returned to human form, he has freed himself from the trap and returned home.

Sir John of course still refuses to believe what Larry tells him, that he has killed Bela and the gravedigger, that he has seen the pentagram in Gwen’s palm. He must leave town, he says. When Colonel Montford comes for Sir John to join the wolf hunt, he straps his son to a chair and takes the silver-handled cane upon Larry’s insistence.

In the woods, Frank and Colonel Montford, armed with shotguns for any wolf contingency, end up chasing a wolf that is after Gwen. Gwen falls unconscious and the wolf turns on Sir John, who uses the cane to kill the animal.

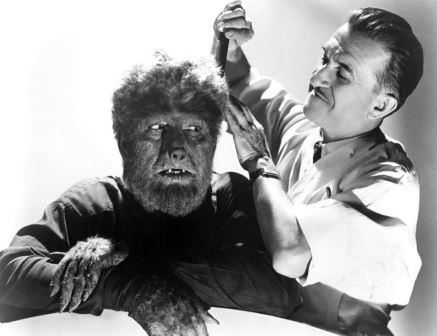

The hunters return just after the wolf has turned back into Larry, who obviously had escaped his bonds. (The two previous human-to-wolf dissolves had been only of feet; now, for the third and last time, seventeen continuous dissolves show the face, the work of special effects expert John P. Fulton and make-up artist Jack Pierce.)

The hunters return just after the wolf has turned back into Larry, who obviously had escaped his bonds. (The two previous human-to-wolf dissolves had been only of feet; now, for the third and last time, seventeen continuous dissolves show the face, the work of special effects expert John P. Fulton and make-up artist Jack Pierce.)

“The wolf must have attacked Gwen,” Montford surmises, “and Larry came to the rescue.” The father, the one most in denial of his son being a werewolf, is now the only one who knows the truth.

By the true nature of the film—The Wolf Man is, after all, a horror film—it’s difficult for elements such as the subtleties of acting or serious character development to be exploited. Claude Rains, however, comes through best of all, as expected, solid and determined, but, for a man with his character’s intelligence, he is a little slow to comprehend the goings-on.

Lon Chaney, in the first of five appearances as the wolf man, is sincere in his portrayal of an innocent man experiencing a series of changes through no fault of his own. At first he is merely suspicions of what he might have done, then haunted by terrible visions and hallucinations beyond his comprehension and finally tormented—practically driven mad—by the realization that he has committed murder and, in his state, could endanger the life of the woman he loves. Bela Lugosi had actively campaigned for the role, but ended up with his brief, killed-off-early part.

Lon Chaney, in the first of five appearances as the wolf man, is sincere in his portrayal of an innocent man experiencing a series of changes through no fault of his own. At first he is merely suspicions of what he might have done, then haunted by terrible visions and hallucinations beyond his comprehension and finally tormented—practically driven mad—by the realization that he has committed murder and, in his state, could endanger the life of the woman he loves. Bela Lugosi had actively campaigned for the role, but ended up with his brief, killed-off-early part.

Evelyn Ankers and Maria Ouspenskaya, two quite different actresses in age and persona, serve well two extremes—the attractive love interest for Chaney and, talk about sincerity, the more than credible gypsy who delivers her hocus-pocus nonsense so convincingly she could have been recruited from an authentic band of gypsies, much as Jan Rubes as the Amish patriarch Eli Lapp in Witness (1985) seems borrowed from that religious sect.

As for the remaining three stars—Ralph Bellamy, Warren William and Patric Knowles, they are pretty much wasted, making a lot of entrances and exits, encumbered by some often trite dialogue. Knowles, for one, is studio-supplied with the props of an English country gentleman, with pipe and tweed coat. The film also features a number of well known supporting players of the ’30s and ’40s: J. M. Kerrigan, Forrester Harvey, Harry Cording, Olaf Hytten and Leyland Hodgson, among others.