“I write with a goose quill dipped in venom.”——Waldo Lydecker

“I write with a goose quill dipped in venom.”——Waldo Lydecker

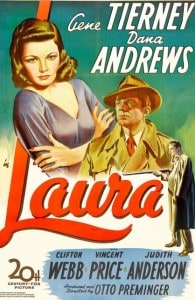

If from Laura you remember the best of Clifton Webb’s acerbic lines and David Raksin’s lush music—and, oh, yes, the long scene where Dana Andrews walks around the “dead” woman’s apartment and stares at her portrait over the fireplace—then you’ve remembered the best parts of the 1944 film that became, almost from the day of its release, the exemplar of the greatest genre of that decade, the film noir.

Just the opening narration—especially that first line—is one of the great introductions in Hollywood history: “I shall never forget the weekend Laura died. A silver sun burned through the sky like a huge magnifying glass. It was the hottest Sunday in my recollection. I felt as if I were the only human being left in New York. For with Laura’s horrible death, I was alone. I, Waldo Lydecker, was the only one who really knew her, and I had just begun to write Laura’s story when another of those detectives came to see me. I had him wait. I could watch him through the half-open door.”

As the camera pans the plush living room and the waiting detective Mark McPherson (Andrews) wanders among the collection of crystal and china, Lydecker (Webb) continues the narration: “I noted that his attention was fixed upon my clock. There was only one other in existence, and that was in Laura’s apartment, in the very room where she was murdered.” The work of a shotgun blast to the woman’s face made her totally unrecognizable, a key element in this murder mystery, and a basis for much misunderstanding and erroneous assumptions.

And don’t forget the floor clock, which chimes while McPherson is waiting. Yes, don’t forget the clock! McPherson will forget it, up until the very last.

And don’t forget the floor clock, which chimes while McPherson is waiting. Yes, don’t forget the clock! McPherson will forget it, up until the very last.

[intlink id=”127″ type=”category”]Gene Tierney[/intlink], now as Laura, “dead” in the first forty-five minutes of the movie, starred in her most famous role despite earlier critical success in Heaven Can Wait and a later Oscar nomination for Leave Her to Heaven. Some say she rendered an even better performance in The Razor’s Edge, but Anne Baxter stole the show as the suffering alcoholic—and won a Supporting Actress Oscar.

In Laura, Clifton Webb as the erudite radio personality and totally self-involved newspaper critic—the subject of himself, he boasts, is “completely justified”—is a less versatile performer, a former Broadway dancer and silent screen obscurity. The uppity character of Lydecker, which many an astute viewer will assume, possibly correctly, to be Webb’s own, would be replicated, even down to his suit and hat, in his next film, The Dark Corner. Same for the part of Elliott Templeton as Tierney’s co-star in The Razor’s Edge. And so his portrayals would continue as variations on Lydecker—in Titanic (1953) and Three Coins in the Fountain (as another writer), and, for that matter, for his best-remembered role as Lynn Belvedere in a series of three films centered around that eccentric character.

Although occupying as much screen time as Andrews or Tierney, Webb was Oscar-nominated for his supporting performance, losing to the cuddly sentimentality of Barry Fitzgerald in Going My Way. This was, after all, during World War II, and although an Allied victory was assured by the time the ballots were counted, the nation was war-exhausted and still needed that warm optimism. Andrews, and rightly so, was not nominated for Best Actor, the award going to—oops, here we go again!—Bing Crosby, Fitzgerald’s fellow, almost-as-cuddly priest in Going My Way.

Although occupying as much screen time as Andrews or Tierney, Webb was Oscar-nominated for his supporting performance, losing to the cuddly sentimentality of Barry Fitzgerald in Going My Way. This was, after all, during World War II, and although an Allied victory was assured by the time the ballots were counted, the nation was war-exhausted and still needed that warm optimism. Andrews, and rightly so, was not nominated for Best Actor, the award going to—oops, here we go again!—Bing Crosby, Fitzgerald’s fellow, almost-as-cuddly priest in Going My Way.

[intlink id=”172″ type=”category”]Dana Andrews[/intlink], the hard, stone-faced detective in Laura, would never again appear in films of the success and quality of “his” decade, the 1940s. Besides Laura, the highlights of those years for him include The Ox-Bow Incident, The Purple Heart, A Walk in the Sun, The Best Years of Our Lives and My Foolish Heart. Later, in 1957, he would appear—still stone-faced as was his inflexible demeanor—in a genre atypical of him, the intelligent horror film Night of the Demon.

The remaining two stars who received screen credit are a young Vincent Price as an unemployed lounge lizard, the actor yet to assume his familiar place as a master of the horrors, and Judith Anderson as Laura’s aunt and Price’s on-and-off-again girlfriend. Anderson never bettered her role as Mrs. Danvers in Rebecca in 1940 despite a half-century of sporadic film appearances and similar ventures as austere women in Kings Row, The Red House and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Maybe the general downturn of her career was partially due to her own somewhat severe facial features.

The remaining two stars who received screen credit are a young Vincent Price as an unemployed lounge lizard, the actor yet to assume his familiar place as a master of the horrors, and Judith Anderson as Laura’s aunt and Price’s on-and-off-again girlfriend. Anderson never bettered her role as Mrs. Danvers in Rebecca in 1940 despite a half-century of sporadic film appearances and similar ventures as austere women in Kings Row, The Red House and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Maybe the general downturn of her career was partially due to her own somewhat severe facial features.