Mistress Mary, quite contrary,

How does your garden grow?

With cockle shells, and silver bells,

And pretty maids all in a row.

The nursery rhyme is a clue for the great Hercule Poirot. For, in the garden, they were not cockle shells, they were oyster shells! Ah, yes, mon Dieu! ——

To the delight of many mystery fanatics, Acorn Media has reissued the various sets of the Hercule Poirot mysteries, with David Suchet as Agatha Christie’s Belgian detective. The series began in 1989 on PBS as part of Mystery!, which also included The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Rumpole of the Bailey, Miss Marple, Inspector Morse and even the medieval Brother Cadfael, with Derek Jacobi as the detective/priest. At last count, the Poirot series comprises some 62 episodes, both the 50- and 100-minute installments. The enterprise is still in progress.

To narrow down such a large oeuvre and possibly entice the uninitiated viewer, this assessment centers on the nine, 50-minute mysteries of Vol. I, based on a sampling of Christie’s short stories, not on the better known novels. Except for the last episode, which originated in Season 3, all come from Season 2.

In one of the two best mysteries, “Double Sin,” the great Poirot, accompanied by his ever-faithful assistant, Captain Hastings (Hugh Fraser), goes to the seaside, to the Midland Hotel, supposedly to relax. As many of the episodes follow a Poirot eccentricity or tie in some gimmick, here Poirot says he is considering retirement, leaving Hastings to investigate the disappearance of twelve, early 19th-century Napoleon miniatures. Hastings’ deductions prove wrong. Poirot, while seeming to idle on the sidelines, has solved the case and exposed the culprits: two women, one in a wheelchair. Whenever a character is in a wheelchair, it’s a good bet the person can walk.

Some picturesque English scenery enhances this episode. And there’s always the humor. It seems that Poirot’s stay at the resort hotel was a ruse—not for the fresh air, which he boasted to Hastings thirty minutes after arriving—but to hear Chief Inspector Japp’s (Philip Jackson) lecture on his police career. Under cover of darkness, Poirot sneaks to the hall. Japp compliments highly the help he has received from the detective, “one of the most original minds of the twentieth century—intelligent, brave, sensitive, devastatingly quick.” Poirot, eavesdropping in the shadows, can only agree with the man’s keen perception.

Some picturesque English scenery enhances this episode. And there’s always the humor. It seems that Poirot’s stay at the resort hotel was a ruse—not for the fresh air, which he boasted to Hastings thirty minutes after arriving—but to hear Chief Inspector Japp’s (Philip Jackson) lecture on his police career. Under cover of darkness, Poirot sneaks to the hall. Japp compliments highly the help he has received from the detective, “one of the most original minds of the twentieth century—intelligent, brave, sensitive, devastatingly quick.” Poirot, eavesdropping in the shadows, can only agree with the man’s keen perception.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was Christie’s first published novel—and, simultaneously, the début of Hercule Poirot. The book appeared in 1920, and “Double Sin,” from a collection of eight short stories, was published forty years later, in 1961. No matter. In Poirot mysteries, certainly in these televised recreations, it’s always the 1930s, the age of art deco, perhaps the pinnacle of elegant women’s fashions, with long dresses, furs, gloves, a time when men, too, wore hats and cars had prominent fenders and headlights.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was Christie’s first published novel—and, simultaneously, the début of Hercule Poirot. The book appeared in 1920, and “Double Sin,” from a collection of eight short stories, was published forty years later, in 1961. No matter. In Poirot mysteries, certainly in these televised recreations, it’s always the 1930s, the age of art deco, perhaps the pinnacle of elegant women’s fashions, with long dresses, furs, gloves, a time when men, too, wore hats and cars had prominent fenders and headlights.

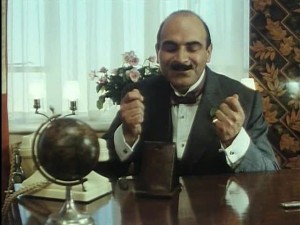

In contrast with Christie’s other famous fictional detective, Miss Jane Marple, who is dowdy, subdued in personality and contrite in her homilies and detection of evil doers, Poirot is unconventional in dress, complete with—always—a suit with stripped pants, bow tie, patent leather shoes, cane, derby, often gloves. Complementing his egg-shaped head is the slicked-down black hair and a waxed mustache, scrupulously trimmed and, of course, always symmetrical.

His personality is eccentric, to the point, it’s been said, of annoyance—obsessive about cleanliness, order and symmetry, a borderline case of compulsive obsessive disorder. A connoisseur of food and drink, he is more than a little conceited and inconsiderate of others, unless his own shortcoming has caused an innocent death, whereupon he’s the most contrite of sinners, as in “The Cornish Mystery” : the death of the wife who came to him with suspicions that her husband was trying to poison her.

Poirot is opinionated and often impatient, though he has a strong work ethic and expects others to have one, too. Whether feigned or not, his unfamiliarity with common English idioms is often comical, such as “throw a hammer into the works,” “quiet as a chapel mouse,” “Poirot does not pull the leg” and “the criminal should not get off Scottish free.”

In the film and TV history of detectives, no character has as much depth, as it were—such a long history and with so many films—as, say, Sherlock Holmes. Jeremy Britts’ Holmes, also jointly from the BBC and PBS’ Mystery!, is a monumental accomplishment all its own. Britts’ impersonation of his character is the most individual, the most vivid of any since, perhaps, Basil Rathbone’s in 1939, early ’40s.

In the film and TV history of detectives, no character has as much depth, as it were—such a long history and with so many films—as, say, Sherlock Holmes. Jeremy Britts’ Holmes, also jointly from the BBC and PBS’ Mystery!, is a monumental accomplishment all its own. Britts’ impersonation of his character is the most individual, the most vivid of any since, perhaps, Basil Rathbone’s in 1939, early ’40s.

And yet no actor has appeared so often in a single role as David Suchet, who is not French—certainly not!—nor even Belgian, but English, born in London in 1946. Despite his other work on stage and in film, he will probably be forever associated with this role, not merely because of the number and proliferation of the Poirot films but because he has so mastered the character, becoming, it seems, the embodiment of Hercule Poirot. Christie, who died in 1976, well before the series, was often critical of film scripts of her work and sometimes withheld her approval, but it is likely she would have proudly endorsed Suchet’s view of this character.

Suchet had his predecessors. The first actor to portray Poirot—on stage in this case—was Charles Laughton in Alibi, adapted from The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which, by the way, many Christie scholars suggest is her best mystery. In the early ’30s, Austin Trevor was the first screen (British) Poirot, though, tall and thin, entirely wrong physically; Trevor said he got the job because he could speak French.

Peter Ustinov played the detective in a number of mediocre films, though Death on the Nile (1978) is brightened by its many big-name stars and the magnificent Egyptian setting. Murder on the Orient Express (1974), reputed to be the most successful British film ever made until Four Weddings and a Funeral, deserves a little more respect than Death on the Nile, though it is likewise over-long and snail-paced. Albert Finney’s Poirot is almost lost beneath the heavy make-up and equally heavy padding. His performance, though nominated for an Oscar, is foiled by his thick accent, often unintelligible.

Peter Ustinov played the detective in a number of mediocre films, though Death on the Nile (1978) is brightened by its many big-name stars and the magnificent Egyptian setting. Murder on the Orient Express (1974), reputed to be the most successful British film ever made until Four Weddings and a Funeral, deserves a little more respect than Death on the Nile, though it is likewise over-long and snail-paced. Albert Finney’s Poirot is almost lost beneath the heavy make-up and equally heavy padding. His performance, though nominated for an Oscar, is foiled by his thick accent, often unintelligible.

The nine mysteries contained on these three DVDs offer an array of circumstances and characters—opium dens, gangsters, mansions of the wealthy (of course), movie stars, political intrigue, disguises, traitors, even two car chases, all mixed in with a good deal of levity, often from Poirot himself or between Hastings and Poirot. Hastings is often baffled by the subtleties of a case and annoyed that he, compared with Poirot, receives less respect from his peers, less response, even, when he tries to hail a taxi, as in “The Adventure of the Western Star.”

The nine mysteries contained on these three DVDs offer an array of circumstances and characters—opium dens, gangsters, mansions of the wealthy (of course), movie stars, political intrigue, disguises, traitors, even two car chases, all mixed in with a good deal of levity, often from Poirot himself or between Hastings and Poirot. Hastings is often baffled by the subtleties of a case and annoyed that he, compared with Poirot, receives less respect from his peers, less response, even, when he tries to hail a taxi, as in “The Adventure of the Western Star.”

In “The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim,” after seeing a magic show, Poirot begins practicing slight of hand, though his somewhat dubious talent is never employed in solving anything. He fails in his final scene, attempting to make an annoying parrot disappear. In “The Veiled Lady,” an excellent installment, Poirot sets up a burglary by posing as a locksmith.

In “The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim,” after seeing a magic show, Poirot begins practicing slight of hand, though his somewhat dubious talent is never employed in solving anything. He fails in his final scene, attempting to make an annoying parrot disappear. In “The Veiled Lady,” an excellent installment, Poirot sets up a burglary by posing as a locksmith.

Similarly, he breaks into an adjoining apartment in “The Adventure of the Cheap Flat.” The episode opens in a movie theater—a shoot-out in a then new Hollywood gangster movie, “G” Men. In response to Hastings’ confusion over some FBI jargon, Poirot advises him “to keep up with the modern idiom.” He should talk! Miss Lemon (Pauline Moran), Poirot’s secretary, even goes undercover as a lady’s companion. Unusual for the series, modernistic, abstract backdrops create New York skyscrapers and evening night club fronts.

Similarly, he breaks into an adjoining apartment in “The Adventure of the Cheap Flat.” The episode opens in a movie theater—a shoot-out in a then new Hollywood gangster movie, “G” Men. In response to Hastings’ confusion over some FBI jargon, Poirot advises him “to keep up with the modern idiom.” He should talk! Miss Lemon (Pauline Moran), Poirot’s secretary, even goes undercover as a lady’s companion. Unusual for the series, modernistic, abstract backdrops create New York skyscrapers and evening night club fronts.

“The Lost Mine” is part of a collection of short stories in Poirot Investigates, published in 1924. At least in the film, there is radio contact with police cars and a tracking map that anticipates the radar tables used during the Battle of Britain. Inspector Japp speaks a variation on one of his favorite lines: “We’re in treacherous waters, indeed.” And Poirot finds Americans, because they place the month before the date, “a most backward people.” Captain Hastings and Poirot are continually playing Monopoly, one of the favorite games of the ’30s. Hastings smugly advises Poirot on the strategy of the game, only to find, in the final scene, that suddenly, inexplicably, Poirot has won. “It is the skill,” he tells his bemused friend, “that counts in the end.”

In a similar way, the underlying humor in “The Kidnapped Prime Minister” is Poirot’s refusal to admit he has gained weight while being fitted for a new suit. For him, the most harrowing part of the investigation is that, in the fade-out, he has to face the tailor for his final fitting. Japp worries throughout about losing his pension, as Poirot seems to be wasting time in locating the minister, much to the annoyance of a government official. Alert viewers, and those who enjoy discovering such things, will note that one of the culprits, played by David Horovitch, is Detective Inspector Slack in a number of the Joan Hickson/Miss Marple BBC series.

In a similar way, the underlying humor in “The Kidnapped Prime Minister” is Poirot’s refusal to admit he has gained weight while being fitted for a new suit. For him, the most harrowing part of the investigation is that, in the fade-out, he has to face the tailor for his final fitting. Japp worries throughout about losing his pension, as Poirot seems to be wasting time in locating the minister, much to the annoyance of a government official. Alert viewers, and those who enjoy discovering such things, will note that one of the culprits, played by David Horovitch, is Detective Inspector Slack in a number of the Joan Hickson/Miss Marple BBC series.

Further searches for actor crossovers in different series are possibly interesting—yes, but potentially endless. For example, Derek Benfield, who died in 2009 and plays Dr. Adams in “The Cornish Mystery,” was also Patricia Routledge’s husband in Hetty Wainthropp Investigates as well as the recurring role of Albert Handyside in Rumpole of the Bailey.

“Are you feeling better, Hastings?” asks an annoyed Poirot in the opening of “The Cornish Mystery.” Hastings, sitting on the floor, is taking breathing exercises—for his pancreas, he explains. Poirot suggests that, no, it is not the pancreas that should concern him but the liver, for “Look after the liver and life will take care of itself.” Without any crucial evidence, Poirot tricks the killer into signing a confession, and then, in a strangely unPoirotian move, guarantees the man a twenty-four hour head start before he notifies the police, then reneges on his word.

“Are you feeling better, Hastings?” asks an annoyed Poirot in the opening of “The Cornish Mystery.” Hastings, sitting on the floor, is taking breathing exercises—for his pancreas, he explains. Poirot suggests that, no, it is not the pancreas that should concern him but the liver, for “Look after the liver and life will take care of itself.” Without any crucial evidence, Poirot tricks the killer into signing a confession, and then, in a strangely unPoirotian move, guarantees the man a twenty-four hour head start before he notifies the police, then reneges on his word.

In “The Adventure of the Western Star”—not about a ship or a movie idol but about a stolen diamond—Poirot is preparing a fastidious dinner for a great Belgian film star who cancels. Hastings displeases the detective by saying he didn’t know Belgium had any film stars! Perhaps from the experience gained earlier in the disappearance of Mr. Davenheim, Poirot uses slight of hand to switch a paste diamond with a real one.

The second of the “two best” episodes alluded to earlier? The only installment from Season 3, “How Does Your Garden Grow?” is, ideally, the last mystery on the third disc. It just might be the best. Originally part of another collection of short stories, Poirot’s Early Cases (1974), it has the best elements of the Christie mystery. The murder occurs in a home of the gentry, aided by a healthy dose of good old English villainy, and, as everyone knows, all “proper” English murderers use poison—less messy—in this case strychnine. There’s a touch of foreign intrigue, too.

The quotable Poirot quote this time is “What a simpleton I have become!” He realizes he has been overlooking the obvious. The darkest possible emphasis is directed toward a red herring, so obvious that it won’t mislead many viewers. Most important, there are abundant clues: the dinner bell buried in the garden, the image of a late Russian czar, the oyster shell flower bed edging, the strychnine in the servant’s room and, above all, from the soon-to-be victim, the small gift for Poirot of a packet of flower seeds—without any seeds!

The quotable Poirot quote this time is “What a simpleton I have become!” He realizes he has been overlooking the obvious. The darkest possible emphasis is directed toward a red herring, so obvious that it won’t mislead many viewers. Most important, there are abundant clues: the dinner bell buried in the garden, the image of a late Russian czar, the oyster shell flower bed edging, the strychnine in the servant’s room and, above all, from the soon-to-be victim, the small gift for Poirot of a packet of flower seeds—without any seeds!

Comic relief is provided, most reliably as always, by Captain Hastings, who, due to an attack of hay fever, secludes himself in Poirot’s flat—just long enough to upset Miss Lemon’s files. While the wrong person sits in jail for the murder, as Poirot well knows, the detective arrives in the garden where the remaining characters are gathered and confronts the real murderers with his usual irrefutable evidence. The episode is marred, however, when the wife, somewhat unrealistically, grabs a pitchfork and runs about the garden in a vindictive tirade; she attempts suicide by drinking from a bottle labeled “weed killer,” which, to deepen her rage, contains whisky, a ploy by her husband to imbibe openly.

Comic relief is provided, most reliably as always, by Captain Hastings, who, due to an attack of hay fever, secludes himself in Poirot’s flat—just long enough to upset Miss Lemon’s files. While the wrong person sits in jail for the murder, as Poirot well knows, the detective arrives in the garden where the remaining characters are gathered and confronts the real murderers with his usual irrefutable evidence. The episode is marred, however, when the wife, somewhat unrealistically, grabs a pitchfork and runs about the garden in a vindictive tirade; she attempts suicide by drinking from a bottle labeled “weed killer,” which, to deepen her rage, contains whisky, a ploy by her husband to imbibe openly.

The cliché now would be “great fun was had by all.” Well, it’s true. While one or two mysteries are unnecessarily complicated, all nine are pleasures to watch, each in its own way. Individually, they are long enough to divert the mind from the worrisome intrusions of the day and, viewed in a cluster, afford time to finish off the entire bag of potato chips! Who better than Hercule Poirot to give advice and reassurance in these trying times? After all, to best control the blood pressure, regardless of one’s preference, pancreas or liver, there’s no need, as Poirot would caution, to “make hills out of the mole mounds.”

Acorn Media also has three other Poirot sets available (pictured below).