“They talk about flat-footed policemen. May the saints protect us from the gifted amateur.” —— Chief Inspector Hubbard (John Williams)

In 1948, [intlink id=”8″ type=”category”]Alfred Hitchcock[/intlink], by then well established in Hollywood, had experimented in shooting an entire film, Rope, without cuts or editing, in continuous reels of film, and four films earlier—his seventh in Hollywood—he had limited himself in yet another way by setting an entire film, Lifeboat, in such a sea-going craft. These were two challenges Hitch set for himself—the first unsatisfactory, the second a guarded triumph; but he never fully tackled either technique again.

In 1954, another challenge was more or less forced on him. Warner Bros. at the time was in the financial doldrums, suffering, as were all the studios, from the advent of practical television and its growing popularity. CinemaScope, launched by 20th Century-Fox in 1953 with The Robe, was just one attempt to lure viewers to the theaters. Still another was impractical 3-D, short-lived until its recent revival in selected action films.

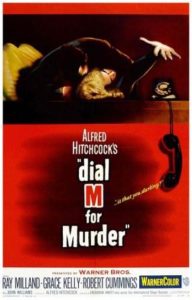

In Dial M for Murder, the first movie to be made after Warner’s supposed new strategy to regain audiences, was to be filmed in 3-D. Hitchcock, unexcited by the new process from the first, immediately saw its limitations. The two bulky cameras—even bulkier than the Technicolor ones, and this film would be in color—meant limited angles and restricted movement, both important trademarks in Hitch’s screen persona. Since the film was based on Frederick Knott’s stage play—the Englishman also wrote the screenplay—the director filmed it in a more or less straightforward manner, as a play, limiting himself to basically one set, a London flat, and going “outside” as little as possible.

The few 3-D effects, though none are over-the-top, did emphasis an open lady’s purse, a key inserted into a door lock and the murder weapon, a soon-to-be famous pair of scissors. The cameras are usually kept low, their limited mobility compensated by more than the usual amount of Hitchcock close-ups. The generally stationary cameras, however, would be partially freed on at least two occasions—an overhead shot of the two men planning the murder and a revolving shot of the victim on a desk top struggling against the assailant.

The few 3-D effects, though none are over-the-top, did emphasis an open lady’s purse, a key inserted into a door lock and the murder weapon, a soon-to-be famous pair of scissors. The cameras are usually kept low, their limited mobility compensated by more than the usual amount of Hitchcock close-ups. The generally stationary cameras, however, would be partially freed on at least two occasions—an overhead shot of the two men planning the murder and a revolving shot of the victim on a desk top struggling against the assailant.