“Tell me corporal. Which is more important, a corporal or a general?” — General Tanz

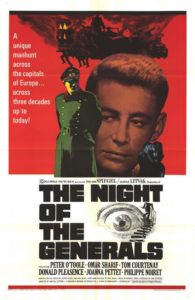

Despite being less than a top-notch film, The Night of the Generals is one of my guilty pleasures. I wallow in the enjoyment of it when, true, I could be watching a better movie.

The 1967 film borders on mediocrity, close to a cinematic blunder, in fact. The sad paradox lies in what might have been, all that potential when its creators had that first spark of inspiration. With a better handling of the camera, a tightening of the script, more attention to German military echelon and uniforms and, somehow, a kindling of real enthusiasm from both director Anatole Litvak and his actors, this “night” of a movie, as it were, might have made a craftily interesting World War II yarn.

Seems like a lot was against it.

Essentially a murder mystery during the Nazi occupation of Europe, the plot includes an uptight psychopathic general, a decent and tenacious military detective, a love story involving neither of them and a plot to kill Adolf Hitler. The plot was not one fabricated in the script, nor even one of the numerous minor assassination attempts against the Führer, but the most famous one—and the most disastrous for the almost 5,000 who were executed—the plot of July 20, 1944, led by Claus von Stauffenberg.

In at least one plus, the film is generally faithful to its source, Hans Hellmut Kirst’s 1965 novel, Die Nacht der Generale, translated into English as The Night of the Generals. The multiple layers of plot that are handled so well in the novel—Kirst (1914-1989) is always chillingly vivid in writing about the Third Reich and WWII—emerge, in the movie, as protracted, stodgy and confusing.

In at least one plus, the film is generally faithful to its source, Hans Hellmut Kirst’s 1965 novel, Die Nacht der Generale, translated into English as The Night of the Generals. The multiple layers of plot that are handled so well in the novel—Kirst (1914-1989) is always chillingly vivid in writing about the Third Reich and WWII—emerge, in the movie, as protracted, stodgy and confusing.

Maurice Jarre writes a deliberately jarring, one might say even ugly, main title, with a disjointed introduction of drums and cymbals, followed by the repeated five-note “insanity” motif that will underline the psychological, even psychopathological, overtones of the film. This motif is mingled with a fragmentary, goose-stepping march and the equally vague suggestions of a waltz.

The film opens in 1942, in the dark and narrow staircase of a Warsaw hotel. The absence of music in the first scene is doubly effective. All that is heard are the heavy footsteps, intentionally amplified, of a hotel clerk. The man hears a commotion—a woman’s scream, a door close, hurried footsteps—and, knowing to be prudent in Nazi-occupied Warsaw, hides in a water closet. Through a hole in the door he can see only the lower half of the man who descends the stairs—and the familiar uniform of a German officer, trousers distinguished by a red stripe.

A German military investigator, Major Grau (Omar Sharif), arrives to find the grisly sex murder of a prostitute, who also happens to be a German agent. He is an idealist, a seeker of justice, whoever the murderer. When the Polish police inspector, Liesowski (Yves Brainville), who summoned Grau to the scene asks if justice also applies to Germans, Grau replies, “If the general is responsible, I shall have to hang him.” Hearing the clerk’s description of the trousers, Grau knows that only German generals’ uniforms have the red stripe.

A German military investigator, Major Grau (Omar Sharif), arrives to find the grisly sex murder of a prostitute, who also happens to be a German agent. He is an idealist, a seeker of justice, whoever the murderer. When the Polish police inspector, Liesowski (Yves Brainville), who summoned Grau to the scene asks if justice also applies to Germans, Grau replies, “If the general is responsible, I shall have to hang him.” Hearing the clerk’s description of the trousers, Grau knows that only German generals’ uniforms have the red stripe.