“I’m shakin’ the dust of this crummy little town off my feet and I’m gonna see the world—Italy, Greece, the Parthenon, the Colosseum. . . . And then I’m gonna build things. I’m gonna build airfields. I’m gonna build skyscrapers a hundred stories high. I’m gonna build bridges a mile long.” —George Bailey to Mary Hatch

Poor George Bailey, as you know if you’ve seen It’s a Wonderful Life, didn’t get to do any of those things. He never got out of Bedford Falls, that “crummy little town.” First, there was his father’s death, and, to prevent the Building and Loan being taken over by the town miser Mr. Potter, who owned and ran practically everything else in town, George assumed the responsibility. Second, there was his brother who was to take over the bank after he left the service, but he had gotten married and had other plans. Then there was George’s own marriage, against his self-interests—and the “drafty old house” to boot. Finally, if all this wasn’t enough and a sufficient sign that he wasn’t going anywhere, Uncle Billy misplaced $8,000 of the bank’s money.

“Where’s that money, you silly, stupid old fool?” George shouts. “Where’s that money? Do you realize what this means? It means bankruptcy and scandal and prison. That’s what it means. One of us is going to jail. Well, it’s not gonna be me.”

And then it becomes really dark for George Bailey. Thoughts of suicide. The missing money can’t be found. He’s at his wits end. But fortunately, and for his sake and the need of the plot, he’s saved by an angel from Outer Space sent to help him. George is about to jump off a bridge to drown his dispair when he’s distracted by someone floundering in the river.

“Help! Help!” A lot of splashing.

Being a really good guy, as better than the first half of the movie has well established, George Bailey’s natural instinct is to dive in and rescue this poor soul. And so he does. Perhaps this someone needs a kind of deliverance himself. As the angel, Clarence Oddbody, would later boast, he pulled this drowning stunt to save George, knowing George would save him.

While the two are drying out in the bridge tender’s shed, Clarence realizes he isn’t doing too well educating his charge on seeing the light, the error of his ways, how thankful he should be and all that. So far, George’s stubbornness is making the job all the more difficult, and when George casually remarks that he wishes he had never been born, the angel has an idea. After conferring with an associate above who seems to think it’s a good idea, Clarence grants George his wish.

Okay, official: He’s never been born. A gust of wind blows open the door to symbolize that the transaction has been initiated from above, and George slips into another world entirely. Suddenly he can hear out of his left ear, for the first time since he was a kid. His bruised lip, a gift from an irate father, has stopped bleeding. And the clothes on the line, wet from the river a moment ago, are inexplicably dry.

After perhaps its funniest scene, Wonderful Life turns darker yet, and remains so for most of the remainder of the film. Clarence follows George around Bedford Falls. George, of course, is trying to re-establish his identity, and for the longest time it doesn’t sink in what has happened. No one seems to know him—not Nick the bartender, and the name of his place has been changed; not Mr. Gower, who, since the last time George saw him, has become a drunken bum; not his two best buddies, Bert the cop on the beat, or Ernie, the cab driver; not his wife Mary, who is now an old maid librarian with the most unattractive wire spectacles; not even, it seems, his own mother, who won’t let him in the front door of her boarding house.

After perhaps its funniest scene, Wonderful Life turns darker yet, and remains so for most of the remainder of the film. Clarence follows George around Bedford Falls. George, of course, is trying to re-establish his identity, and for the longest time it doesn’t sink in what has happened. No one seems to know him—not Nick the bartender, and the name of his place has been changed; not Mr. Gower, who, since the last time George saw him, has become a drunken bum; not his two best buddies, Bert the cop on the beat, or Ernie, the cab driver; not his wife Mary, who is now an old maid librarian with the most unattractive wire spectacles; not even, it seems, his own mother, who won’t let him in the front door of her boarding house.

In a macabre scene—the darkest of the film—Clarence takes George to what before had been George’s low-cost housing development but is now a cemetery. There in the snow is Harry Bailey’s childhood grave. Why? Clarence explains. As having never lived, George wasn’t there to save his brother when he fell in the icy pond, so Harry wasn’t there to save those men’s lives in the war.

The scene recalls A Christmas Carol when the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Be shows Scrooge his own grave. Much in the film owes its inspiration to Charles Dickens’ novella: Clarence resembles two of the Christmas ghosts, of the Present and the Past, the misery Potter substitutes easily for Scrooge and, most obvious, there is the redemption of a lost soul through a spiritual deliverer.

Bedford Falls has become Pottersville, and as George walks down the main street, he finds it greatly changed. The Building and Loan is no longer there, having gone out of business years ago, he is told. Can that be right? And the conservative, friendly store fronts are now girlie shows, bars and gambling dens. And all those gaudy neon, flashing and blinking!

Hey, what’s going on here?!

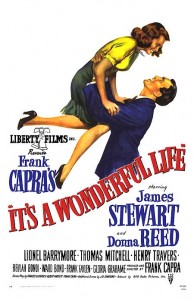

Although premiered in New York, December 20, 1946, Wonderful Life was never intended as a Christmas movie. It was an initial box office flop. Regarded as old-fashioned at the time, it won none of its five Oscar nominations, which included picture, actor and director. But because TV stations in the 1970s took advantage of the film’s copyright expiration—no fee for airing—it has become a staple of the holiday season.

It was both James Stewart’s and Frank Capra’s first film after their service in World War II, the actor having been a bomber commander, the director a documentary film maker. Stewart doubted that he could regain his pre-war success, doubtful, too, that acting was a respectable calling after his momentous efforts in the war. Lionel Barrymore, who starred as Mr. Potter, convinced him that acting was the greatest profession in the world. “After a week or so of working,” Stewart said, “I just knew that it was gonna be all right . . . and I hadn’t forgotten the things I’d learned before the war. It still meant a lot to me. I could have sworn that I’d never been away.”

It was both James Stewart’s and Frank Capra’s first film after their service in World War II, the actor having been a bomber commander, the director a documentary film maker. Stewart doubted that he could regain his pre-war success, doubtful, too, that acting was a respectable calling after his momentous efforts in the war. Lionel Barrymore, who starred as Mr. Potter, convinced him that acting was the greatest profession in the world. “After a week or so of working,” Stewart said, “I just knew that it was gonna be all right . . . and I hadn’t forgotten the things I’d learned before the war. It still meant a lot to me. I could have sworn that I’d never been away.”