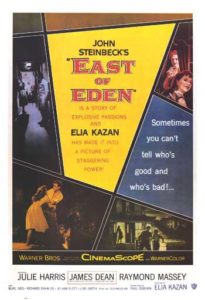

“Tonight I even tried to buy your love, but now I don’t want it any more. . . . I can’t use it any more. I don’t want any kind of love any more. It doesn’t pay off.” —— Cal (James Dean) to Abra (Julie Harris)

Above all, East of Eden is about love—paternal, maternal, fraternal and the romantic love between a man and a woman; it’s about love being sought, envied, misguided, denied, abandoned, even cursed.

Love is not necessarily a specialty in John Steinbeck novels and short stories, many of which have been filmed—more, in fact, than the plays of Tennessee Williams, another writer, along with John O’Hara, who specializes in the underside of life. Steinbeck’s characters are usually about the downtrodden, people on the move (The Grapes of Wrath) or in desperate jobs (Of Mice and Men) or without jobs (Cannery Row); some of his works touch on lighter subjects—a boy’s love for an animal and his acceptance of responsibility (The Red Pony) or an autobiographical travelogue across the U.S. (Travels with Charlie: In Search of America).

East of Eden, which Steinbeck wrote in 1952, has a strong Biblical subtext of good and evil. Set in 1917-18, just before and after the U.S.’s entry into World War I, the evil subsists throughout the film, at times darkly in the foreground, at other times masked amid the varieties of love, or lack thereof, residing in characters who often have, quite appropriately and by no means accidentally, Biblical or Bible-like names.

Appearing at the beginning of the film, dressed in black, a wide-brimmed hat and veil, is Kate (Jo Van Fleet in her big screen début), presumed dead but very much alive as the madam of a brothel. There is the anonymous presence of evil in the collective images, visual and audial—the empty streets, the frequent long shots, Leonard Rosenman’s unsettling music and the resolute walk of that figure in black. From among a group of seated men, one man taunts her as she passes and kicks at her skirt. She walks on, unresponsive. The audience can easily assume the woman is from the shady side of life, probably exactly what she is.

Appearing at the beginning of the film, dressed in black, a wide-brimmed hat and veil, is Kate (Jo Van Fleet in her big screen début), presumed dead but very much alive as the madam of a brothel. There is the anonymous presence of evil in the collective images, visual and audial—the empty streets, the frequent long shots, Leonard Rosenman’s unsettling music and the resolute walk of that figure in black. From among a group of seated men, one man taunts her as she passes and kicks at her skirt. She walks on, unresponsive. The audience can easily assume the woman is from the shady side of life, probably exactly what she is.

Kate is the mother of Cal Trask (James Dean)—short for the Old Testament Caleb—who has followed her and wonders if this woman is, indeed, his mother. But, more important, he wants the love of his stern, Bible-reading father Adam (Raymond Massey), a vegetable farmer who has some early, though untested ideas about railway refrigeration. Note the name: Adam, the first man to exist, if one believes in the allegory of the Garden of Eden, just east of where Steinbeck’s story is presumably taking place.

Kate is the mother of Cal Trask (James Dean)—short for the Old Testament Caleb—who has followed her and wonders if this woman is, indeed, his mother. But, more important, he wants the love of his stern, Bible-reading father Adam (Raymond Massey), a vegetable farmer who has some early, though untested ideas about railway refrigeration. Note the name: Adam, the first man to exist, if one believes in the allegory of the Garden of Eden, just east of where Steinbeck’s story is presumably taking place.

Completing this family quartet is the other son, the father’s favorite, the presumed “good” son, Aron (Richard Davalos, also in his theatrical film début), whose name is another spelling of Aaron, the older brother of Moses. Aron is in love with Abra (Julie Harris), who returns his love at film’s beginning. While meaning “four” in Hebrew and also “mother of many,” Abra is the name of an obscure man in the Old Testament.

For his work in adapting the last third of Steinbeck’s sprawling novel, screenwriter Paul Osborn received an Oscar nomination, as did Elia Kazan for his direction. The only other nomination—successful—was Best Supporting Actress for Jo Van Fleet. Doing much of her work in television, and some would say her best, she did make significant impressions in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and Cool Hand Luke.

Much like other directors, Alfred Hitchcock and John Huston among many, Kazan was a master at manipulating, coercing and incensing his actors to deliver the performances he wanted. To achieve his desired results, Kazan even got Dean intoxicated for one of his scenes with Harris. He encouraged the animosity between Massey and Dean whenever possible; Massey heartily disliked the young actor and scorned what he considered his impulsive unprofessionalism. Nor blameless was Dean, who incited Massey’s anger to spur his own motivations.

Much like other directors, Alfred Hitchcock and John Huston among many, Kazan was a master at manipulating, coercing and incensing his actors to deliver the performances he wanted. To achieve his desired results, Kazan even got Dean intoxicated for one of his scenes with Harris. He encouraged the animosity between Massey and Dean whenever possible; Massey heartily disliked the young actor and scorned what he considered his impulsive unprofessionalism. Nor blameless was Dean, who incited Massey’s anger to spur his own motivations.

So, clearly, those involved worked hard to make this an unhappy set. But look at the results!

Rosenman’s part in making East of Eden a masterful film has already been implied—more about his music later—and cinematographer Ted McCord also deserves immense credit. This was, remember, the era of early CinemaScope when the best use of the new screen ratio was still in an experimental stage. McCord handles the new lens like an expert.

On the one hand, McCord makes a deliberate effort to fill the screen with interesting outside visuals—streets, meadows, carnivals, numerous trains. There are several especially arresting shots which excite the eye and give a kind of aesthetic pleasure, perhaps a subliminal relief from the dark undertow of the story line. One occurs early in the film when Cal is returning home to Salinas, California, from Monterey. Having followed the woman in black to a Victorian house and been denied entry, he now climbs aboard a freight train, sitting on the top of a car, huddled against the cold in his sweater, a vast landscape stretching in the distance ahead of the train.

On the one hand, McCord makes a deliberate effort to fill the screen with interesting outside visuals—streets, meadows, carnivals, numerous trains. There are several especially arresting shots which excite the eye and give a kind of aesthetic pleasure, perhaps a subliminal relief from the dark undertow of the story line. One occurs early in the film when Cal is returning home to Salinas, California, from Monterey. Having followed the woman in black to a Victorian house and been denied entry, he now climbs aboard a freight train, sitting on the top of a car, huddled against the cold in his sweater, a vast landscape stretching in the distance ahead of the train.

In another scene involving a train, the caboose is seen at the left of the railway station, which conceals the rest of the train. As McCord’s camera follows Adam to the right, the front of the train comes into view, moving off across a vast landscape of farm crops. As Adam leans against the far corner of the building, obviously admiring the view, Cal stands at the corner behind him, never approaching his father. Why this shot, something like a Thomas Hart Benson painting, is so impressive it’s hard to say, other than it shows the “distance” between father and son.

On the other hand, McCord’s tilted angles and his sometimes bleakly emphatic chiaroscuro add a sense of disquiet—the wide, empty streets, the shabbiness of Kate’s cluttered room, the confines of an ice house attic, Adam’s claustrophobic dining room. Too, these scenes produce an uneasy feeling of guilt, as of a voyeur witnessing the inner, shadowy secrets of people’s lives that are best left unobserved.

On the other hand, McCord’s tilted angles and his sometimes bleakly emphatic chiaroscuro add a sense of disquiet—the wide, empty streets, the shabbiness of Kate’s cluttered room, the confines of an ice house attic, Adam’s claustrophobic dining room. Too, these scenes produce an uneasy feeling of guilt, as of a voyeur witnessing the inner, shadowy secrets of people’s lives that are best left unobserved.

In one of the most memorable scenes in the film, perhaps because it is such a clear revelation of the animosity between Adam and Cal, with the claustrophobic set adding its own touch, Adam, Cal and Aron are at their small dining room table. As an apparent “honor,” Adam passes Cal a Bible and asks him to read. For a son trying to earn his father’s love, he is counterintuitive, deliberately antagonistic, and his father, being who he is, is unnecessarily critical and impatient.

In one of the most memorable scenes in the film, perhaps because it is such a clear revelation of the animosity between Adam and Cal, with the claustrophobic set adding its own touch, Adam, Cal and Aron are at their small dining room table. As an apparent “honor,” Adam passes Cal a Bible and asks him to read. For a son trying to earn his father’s love, he is counterintuitive, deliberately antagonistic, and his father, being who he is, is unnecessarily critical and impatient.

Cal begins reading Psalm 32: “Five. I acknowledge my sin unto thee, and mine iniquity have I not hidden. . . . Selah.” The father suggests he read a little slower and omit the verse numbers. Cal reads the next verse, again reciting the verse number. “Not the numbers, Cal . . . ” And when Cal includes the number yet again, Adam explodes: “You have no repentance! You’re bad! Through and through—bad!” It’s as though he were cursing a dog for soiling the carpet.

Another scene among the two teenage brothers (Dean and Davalos are both 24) and Abra (Harris, 30) is shot oddly by conventional standards, with the low-hanging foliage of a tree as the centerpiece. The stars act around, behind and even inside the branches and, if seen, sometimes have their backs to the camera, with occasional seemingly disembodied voices. Aron tells Cal to stay away from his girl, who had responded to Cal’s kiss on the carnival Ferris wheel while, at the same time, protesting she still loves Aron.

Another scene among the two teenage brothers (Dean and Davalos are both 24) and Abra (Harris, 30) is shot oddly by conventional standards, with the low-hanging foliage of a tree as the centerpiece. The stars act around, behind and even inside the branches and, if seen, sometimes have their backs to the camera, with occasional seemingly disembodied voices. Aron tells Cal to stay away from his girl, who had responded to Cal’s kiss on the carnival Ferris wheel while, at the same time, protesting she still loves Aron.

After his father’s near-bankruptcy over loss on a lettuce shipment, Cal, on a second, more cordial meeting with his mother (the first was disastrous, she ordering him thrown out), she loans him $5,000 to invest in a bean crop. Successful in the venture and searching for another way to win his father’s love, Cal surprises Adam on his birthday with the money to replace what he had lost. Adam refuses the cash, saying it was earned from war profiteering.

In the script, Dean was supposed to turn away in distress and run howling, like a wounded animal, from the room. He does do that, but, first, unscripted, he embraces his father. Massey, not a method actor and unaccustomed to improvisation, could only respond, “Cal. Cal.” The shot remained in the released print.

In the script, Dean was supposed to turn away in distress and run howling, like a wounded animal, from the room. He does do that, but, first, unscripted, he embraces his father. Massey, not a method actor and unaccustomed to improvisation, could only respond, “Cal. Cal.” The shot remained in the released print.

In the next scene Cal tells Aron he has something to show him and takes him to see his mother, whom Aron believes is dead. “Say ‘hello’ to you mother, Aron!” It is one of the most harrowing scenes in the film, shot in the confines of a hallway and in Kate’s room, with Aron groveling on the floor. It is cruel on Cal’s part, especially after he had earlier come to Aron’s defense in a city brawl over the war.

Having seen his mother, and angry at his father for keeping her existence from him, Aron gets drunk and boards a train with plans to join the Army and fight in a war he had originally opposed. When Adam learns from the town sheriff (Burl Ives) of the boy’s plans, he rushes to the train station, only to be denounced by his son. Aron smashes the passenger coach window with his forehead, laughing hysterically as the train pulls out, moving left to right as most of the trains have done in the film.

Having seen his mother, and angry at his father for keeping her existence from him, Aron gets drunk and boards a train with plans to join the Army and fight in a war he had originally opposed. When Adam learns from the town sheriff (Burl Ives) of the boy’s plans, he rushes to the train station, only to be denounced by his son. Aron smashes the passenger coach window with his forehead, laughing hysterically as the train pulls out, moving left to right as most of the trains have done in the film.

Adam suffers a stroke and is placed in bed where he remains semiconscious. Cal talks to him, but there is no response. Abra, who by now has transferred her love to Cal, urges him to try again to communicate. This time his father responds, murmuring that he should dismiss the nurse, that only Cal should take care of him. A love reclaimed or earned for the first time? Cal pulls up a chair and sits by his father as the film ends.

That East of Eden came to be Leonard Rosenman’s first film score is due to two artists involved in the movie. James Dean, who was a student in Rosenman’s piano class, suggested that Kazan attend a concert Rosenman was giving in New York. Impressed by what he heard, Kazan asked if the composer would like to score his current film.

That East of Eden came to be Leonard Rosenman’s first film score is due to two artists involved in the movie. James Dean, who was a student in Rosenman’s piano class, suggested that Kazan attend a concert Rosenman was giving in New York. Impressed by what he heard, Kazan asked if the composer would like to score his current film.

At the time, Rosenman was already establishing himself as one of those so-called “modernist” composers—whatever that broad term means—having been a student of twelve-tone pioneer Aaron Schoenberg, and the East of Eden score is full of dissonances and other sounds that couldn’t be called “melodic” in the Hollywood film score tradition. That same year—he was, indeed, busy in 1955—Rosenman would score Vincente Minnelli’s The Cobweb, not much of a film, though the music is possibly the first to contain a twelve-tone row.

Setting the mood for the generally gloomy story to follow, musical discord is heard immediately in the main title, though, soon, a soft, more traditional melody serves as the love theme, which some call “Coplandish,” though I’m not so sure: it is, perhaps, simply the harmonic side of Rosenman’s musical personality. In an instance where soundtrack music becomes source music, Aron and Abra hum the tune in the ice house. Later, back in the orchestra, the melody serves to represent, now, Cal and Abra’s love when they kiss on the Ferris wheel, and it will close the film as Cal sits beside his father’s bed.

Setting the mood for the generally gloomy story to follow, musical discord is heard immediately in the main title, though, soon, a soft, more traditional melody serves as the love theme, which some call “Coplandish,” though I’m not so sure: it is, perhaps, simply the harmonic side of Rosenman’s musical personality. In an instance where soundtrack music becomes source music, Aron and Abra hum the tune in the ice house. Later, back in the orchestra, the melody serves to represent, now, Cal and Abra’s love when they kiss on the Ferris wheel, and it will close the film as Cal sits beside his father’s bed.

Rosenman would also compose that same year the score for Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause, but not for his last-released film Giant, scored by Dimitri Tiomkin. With a few exceptions—Bound for Glory, Barry Lyndon and the animated The Lord of the Rings (1978)—Rosenman was not assigned many big films, and did most of his work in television: Combat!, Marcus Welby, M.D., The Virginian, among many other programs.

East of Eden was the only one of James Dean’s three major films released during his lifetime. He died in the crash of his sports car, September 30, 1955. In July of that year he had filmed an interview (never shown), warning young people to drive more carefully, that “The life you might save might be mine.”

East of Eden was the only one of James Dean’s three major films released during his lifetime. He died in the crash of his sports car, September 30, 1955. In July of that year he had filmed an interview (never shown), warning young people to drive more carefully, that “The life you might save might be mine.”