“Maybe Warner and Wallis had it right all along—with these two sexy kids, the chase was the thing. And the kids believed it, too, until they finally realized that neither was the answer for the other.” —— from Errol & Olivia by Robert Matzen

“I was called for a test, simply a test,” she wrote, “ just to see how the two of us in costume would look together, and that’s when I first met him. And I walked onto the set, and they said, ‘Would you please stand next to Mr. Flynn?’ And I saw him. Oh, my! Oh, my! Struck dumb. I knew it was what the French call a coup de foudre.”

Coup de foudre—love at first sight.

This, on the set of Captain Blood in 1935, was Olivia de Havilland’s immediate impression when meeting the then near-obscure Errol Flynn. At the time, she was only slightly less obscure than he. The relationship of these soon-to-be major stars is the theme of Robert Matzen’s new book, Errol & Olivia: Ego & Obsession in Golden Era Hollywood, and the underlying impetus which makes the reading fascinating. The title is somewhat awkward, much like the title of a later, post-Captain Blood, Olivia/Errol costumer, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, in which she would have only one scene with him, and that brief.

This, on the set of Captain Blood in 1935, was Olivia de Havilland’s immediate impression when meeting the then near-obscure Errol Flynn. At the time, she was only slightly less obscure than he. The relationship of these soon-to-be major stars is the theme of Robert Matzen’s new book, Errol & Olivia: Ego & Obsession in Golden Era Hollywood, and the underlying impetus which makes the reading fascinating. The title is somewhat awkward, much like the title of a later, post-Captain Blood, Olivia/Errol costumer, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, in which she would have only one scene with him, and that brief.

That movie title’s anguished evolution, mainly caused by the ego of Bette Davis, who insisted her presence as Elizabeth I be indicated, is as good a symbol as any of the smoldering mistrusts, often self-imposed miseries and inevitable jealousies that was, and always has been, Hollywood. In two hundred pages, Matzen, who received no counsel from de Havilland, lays bare the attraction/dissension between the two stars, like two negatives or two positives trying to connect. For them both, on and off screen, there was always a counterpoint of conflicts with directors, liaisons with other stars, the ever-looming studio boss Jack L. Warner and, in Flynn’s case, one magnetically sexy wife, Lili Damita.

That movie title’s anguished evolution, mainly caused by the ego of Bette Davis, who insisted her presence as Elizabeth I be indicated, is as good a symbol as any of the smoldering mistrusts, often self-imposed miseries and inevitable jealousies that was, and always has been, Hollywood. In two hundred pages, Matzen, who received no counsel from de Havilland, lays bare the attraction/dissension between the two stars, like two negatives or two positives trying to connect. For them both, on and off screen, there was always a counterpoint of conflicts with directors, liaisons with other stars, the ever-looming studio boss Jack L. Warner and, in Flynn’s case, one magnetically sexy wife, Lili Damita.

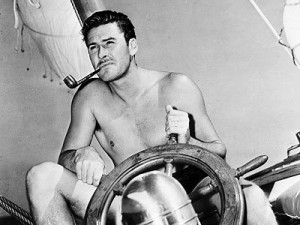

Errol’s fame as a wooer of anything in a dress—he liked the legs long and the ankles slender—has been well documented. Besides the women, there was the booze, the drugs, tardiness on the set, cruel practical jokes (often at Olivia’s expense) and the perpetual fights with Warner and Michael Curtiz, who directed all but one of the pair’s eight films. There was Flynn’s underlying need to escape, either to his lover’s liar on Mulholland Drive or to one of his boats—the ketch “Sirocco” and later the schooner “Zaca.” Above all, to escape responsibility. But what he couldn’t escape, as Matzen points out, was his own feelings of self-loathing. For the first time that I’m aware, the author suggests that Flynn suffered from what today is known as ADHD, which would help explain his erratic personality, combative nature and inability to remember lines.

Errol’s fame as a wooer of anything in a dress—he liked the legs long and the ankles slender—has been well documented. Besides the women, there was the booze, the drugs, tardiness on the set, cruel practical jokes (often at Olivia’s expense) and the perpetual fights with Warner and Michael Curtiz, who directed all but one of the pair’s eight films. There was Flynn’s underlying need to escape, either to his lover’s liar on Mulholland Drive or to one of his boats—the ketch “Sirocco” and later the schooner “Zaca.” Above all, to escape responsibility. But what he couldn’t escape, as Matzen points out, was his own feelings of self-loathing. For the first time that I’m aware, the author suggests that Flynn suffered from what today is known as ADHD, which would help explain his erratic personality, combative nature and inability to remember lines.

De Havilland, as Matzen vividly relates, is, in her way, as insecure as Flynn, although not self-destructive like her co-star. First of all, which was ongoing after Captain Blood, Olivia resented the kind of outdoor adventures she was ordered to make with the actor. Their only movie with a modern-day setting, the dismal comedy Four’s A Crowd, prompted Warner to thereafter confine his romantic team to period epics, which were hits with audiences. In addition, Olivia was a control freak, often depressed, sick (she had appendicitis in 1940 during a promotional tour for Santa Fe Trail), in endless suspensions for refusing inept scripts, upset over both her career and her fitful dealings with Flynn and, at various times, either losing or gaining weight.

De Havilland, as Matzen vividly relates, is, in her way, as insecure as Flynn, although not self-destructive like her co-star. First of all, which was ongoing after Captain Blood, Olivia resented the kind of outdoor adventures she was ordered to make with the actor. Their only movie with a modern-day setting, the dismal comedy Four’s A Crowd, prompted Warner to thereafter confine his romantic team to period epics, which were hits with audiences. In addition, Olivia was a control freak, often depressed, sick (she had appendicitis in 1940 during a promotional tour for Santa Fe Trail), in endless suspensions for refusing inept scripts, upset over both her career and her fitful dealings with Flynn and, at various times, either losing or gaining weight.

Those who have always seen Olivia de Havilland as the innocent virgin she often portrays on screen, largely perpetuated by her films with Flynn, will be in for a surprise, as I was. At the height of her career, when Hollywood was truly “Golden,” she had dalliances with James Stewart, Howard Hughes and John Huston.

And, yes, with Flynn—or so it seems. Whether she “made it” with him is left vague by the author, who excerpts Michael Caine’s book What’s It All About?, repeating Caine’s conversation with Olivia during their filming in 1977 of that geriatric disaster The Swarm. They are walking together when she indicates that a distant hill is where Errol seduced her. After the publication of Caine’s book, she declared she had been misquoted, that she was talking about “making it” with John Huston. As Matzen writes, “But the world hasn’t been nearly as curious about Olivia and John as about Olivia and Errol . . . ”

She divorced her second husband in 1979 and has never remarried, saying herself that she was incapable of a lasting relationship with any man.

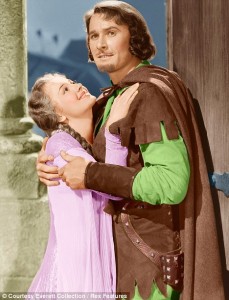

The author’s expected emphasis is on the films Errol and Olivia made together, with only passing references to others. The longest chapters are devoted to their first film, Captain Blood, their last, They Died with Their Boots On, and, in between, their collaborative masterpiece, The Adventures of Robin Hood. The Sea Hawk, the other of Flynn’s two absolute “best” films alongside Robin Hood, is casually mentioned, omitting his being saddled with so wooden a leading lady as Brenda Marshall, due to the absence of his usual partner. Matzen studies in some detail de Havilland’s work in Gone With the Wind, although Errol is not featured, as it was a pivotal film in her career. She had to fight and scheme for the part of Melanie, circumventing Jack Warner to exploit his wife’s influence. As punishment, Warner forced on Olivia the thankless bit part in Elizabeth and Essex, filmed concurrently with GWTW.

The author’s expected emphasis is on the films Errol and Olivia made together, with only passing references to others. The longest chapters are devoted to their first film, Captain Blood, their last, They Died with Their Boots On, and, in between, their collaborative masterpiece, The Adventures of Robin Hood. The Sea Hawk, the other of Flynn’s two absolute “best” films alongside Robin Hood, is casually mentioned, omitting his being saddled with so wooden a leading lady as Brenda Marshall, due to the absence of his usual partner. Matzen studies in some detail de Havilland’s work in Gone With the Wind, although Errol is not featured, as it was a pivotal film in her career. She had to fight and scheme for the part of Melanie, circumventing Jack Warner to exploit his wife’s influence. As punishment, Warner forced on Olivia the thankless bit part in Elizabeth and Essex, filmed concurrently with GWTW.

Matzen’s book highlights many behind-the-scene tales of woe and wonder. In filming Davis and Flynn’s first scene in Elizabeth and Essex, instead of the usual screen slap, she strikes him full face, angering the actor and causing near-mutiny on the set. (In the subsequent retake, a welt on Flynn’s cheek is clearly visible.) In a well known incident, de Havilland encourages Clark Gable, against his instincts, to cry over the death of his daughter Bonnie Blue in GWTW. Producer Hal B. Wallis’ memo blasts director Curtiz during Captain Blood for neglecting an important Flynn close-up and concentrating instead on the composition of a candlestick and a wine bottle on a table in the foreground, which, Wallis shouts from the page, “I don’t give a damn about.”

In fact, Wallis’ literary flair for annoyance, much like David O. Selznick’s infamous memos, is something of a read itself. Most of the Matzen’s extracts from the watchdog producer come in the second chapter, which details the filming of Captain Blood, the flurry of notes obviously justified, as it was the first starring role for the unproven Flynn and the studio had a considerable financial investment at stake. “When you get this note,” Wallis memos Curtiz, “I want you to stop shooting and come up and see me, and I want to find out once and for all why it is that you insist on doing things that I tell you not to do.” More of such angry, sometimes enlightening, thought-sharing would have been welcomed.

In fact, Wallis’ literary flair for annoyance, much like David O. Selznick’s infamous memos, is something of a read itself. Most of the Matzen’s extracts from the watchdog producer come in the second chapter, which details the filming of Captain Blood, the flurry of notes obviously justified, as it was the first starring role for the unproven Flynn and the studio had a considerable financial investment at stake. “When you get this note,” Wallis memos Curtiz, “I want you to stop shooting and come up and see me, and I want to find out once and for all why it is that you insist on doing things that I tell you not to do.” More of such angry, sometimes enlightening, thought-sharing would have been welcomed.

Flynn frequently upstages his co-star, something, frankly, I had never noticed. In Robin Hood, as he is telling Olivia about the suffering of the Saxon people, huddling there in Sherwood Forest, a crucial moment when Maid Marian softens her earlier dislike for Robin, Errol plays with a twig in his right hand to steal the scene. Later, in Dodge City—in fact my favorite scene, much aided by Max Steiner’s music—the two stars dismount their horses and sit on the ground under a tree. As Errol is relating how pigs got into his mother’s prize roses, he toys with yet another twig. (Interestingly, he is not seen reaching for the prop but it’s inexplicably in his hand at the beginning of a cut.)

Flynn frequently upstages his co-star, something, frankly, I had never noticed. In Robin Hood, as he is telling Olivia about the suffering of the Saxon people, huddling there in Sherwood Forest, a crucial moment when Maid Marian softens her earlier dislike for Robin, Errol plays with a twig in his right hand to steal the scene. Later, in Dodge City—in fact my favorite scene, much aided by Max Steiner’s music—the two stars dismount their horses and sit on the ground under a tree. As Errol is relating how pigs got into his mother’s prize roses, he toys with yet another twig. (Interestingly, he is not seen reaching for the prop but it’s inexplicably in his hand at the beginning of a cut.)

But Olivia has a chance to get even. In their first scene in They Died with Their Boots On, she approaches Flynn who, as a West Point cadet walking punishment duty, is not allowed to speak. While Olivia explains that she’s lost and needs directions, she plays with her handkerchief—“to slyly rib him for so often upstaging her,” Matzen writes.

Olivia was so sure that Robin Hood would be a dud that she didn’t see the film for twenty years. Then one day in Paris in 1959, wondering how to entertain her two children, she took them to a local theater to see it. “I thought the film was adorable,” she later wrote. “I had no idea it was so good. It was enchanting and I thought, good gracious, it’s a classic, it really is a classic! When we made those films, we had no idea what we were making, that we were making the best of their kind.”

Olivia was so sure that Robin Hood would be a dud that she didn’t see the film for twenty years. Then one day in Paris in 1959, wondering how to entertain her two children, she took them to a local theater to see it. “I thought the film was adorable,” she later wrote. “I had no idea it was so good. It was enchanting and I thought, good gracious, it’s a classic, it really is a classic! When we made those films, we had no idea what we were making, that we were making the best of their kind.”

Matzen writes in a serviceable style, nothing special, although the imagined words/thoughts of Jack L. Warner, set in italics, sometime border on the simplistic and the clairvoyant. Uncharacteristically, because it doesn’t happen again, there is a cluster of errors in the plot summary of Captain Blood: the time is actually a century later, Colonel Bishop is not governor of Jamaica when Blood arrives at Port Royal, the British war (King William’s) is against France not Spain and, in the climactic sea battle, Blood fights not “a squadron” of ships but two, and this time, correctly, they are French ships.

Considering their quality and importance in the success of these films, there are few references to the music of Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, who scored, respectively, four and three Errol/Olivia films; the third composer is Heinz Roemheld (Four’s A Crowd). This oversight is a problem I have with Thomas McNulty’s Errol Flynn: The Life and Career, otherwise a thorough and exceptional, perhaps definitive, biography of the actor. This neglect of the music persists with current film criticism, though scores these days usually have little relation with the screen and are of slight consequence as works of “art.”

Although o nly three movie posters are reproduced in Matzen’s book, there is an abundance of other photos—candid shots of the stars at various times in their lives, movie stills and, especially fascinating, location and set pictures. Some particular favorites are Flynn, de Havilland and Guy Kibbee relaxing on the set of Captain Blood; a similar circumstance with the couple on location for Robin Hood; the filming of a love scene in Boots with director Raoul Walsh hovering over them; and two-page spreads of Olivia and Errol on social nights out with the likes of David Niven and Basil Rathbone and on a train during a promotional jaunt for Santa Fe Trail (they seem to be enjoying each other’s company immensely).

nly three movie posters are reproduced in Matzen’s book, there is an abundance of other photos—candid shots of the stars at various times in their lives, movie stills and, especially fascinating, location and set pictures. Some particular favorites are Flynn, de Havilland and Guy Kibbee relaxing on the set of Captain Blood; a similar circumstance with the couple on location for Robin Hood; the filming of a love scene in Boots with director Raoul Walsh hovering over them; and two-page spreads of Olivia and Errol on social nights out with the likes of David Niven and Basil Rathbone and on a train during a promotional jaunt for Santa Fe Trail (they seem to be enjoying each other’s company immensely).

For movie fans, especially those who follow Errol and Olivia, the book receives a definite thumbs up.

On the surface, Matzen’s work might seem to be a love story. Not by a long shot. It is, unfortunately, a tale of a strange, somehow misguided kind of love, one tragically unhappy and unfulfilled. From all indications, the two stars really did love one another but were held back—Olivia because Flynn was married most of the time to one of three wives and until his death; Flynn perhaps because his naturally duplicitous nature made him incapable of sustaining a monogamous relationship.

On the surface, Matzen’s work might seem to be a love story. Not by a long shot. It is, unfortunately, a tale of a strange, somehow misguided kind of love, one tragically unhappy and unfulfilled. From all indications, the two stars really did love one another but were held back—Olivia because Flynn was married most of the time to one of three wives and until his death; Flynn perhaps because his naturally duplicitous nature made him incapable of sustaining a monogamous relationship.

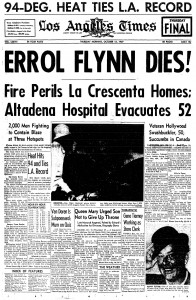

While Errol’s rapid downward spiral was well under way—he would die in 1959, age fifty—Olivia would gain, if only briefly in the late 1940s, the quality roles she had always craved. Within a period of four years, she would be nominated for The Snake Pit (earlier for GWTW and Hold Back the Dawn) and win Oscars for To Each His Own and The Heiress.

While Errol’s rapid downward spiral was well under way—he would die in 1959, age fifty—Olivia would gain, if only briefly in the late 1940s, the quality roles she had always craved. Within a period of four years, she would be nominated for The Snake Pit (earlier for GWTW and Hold Back the Dawn) and win Oscars for To Each His Own and The Heiress.

In her often-related story, at a party in 1958 for the recently completed The Proud Rebel, Olivia is startled by a kiss on the back of her neck. She turns around angrily and says, “Do I know you?” And realizes it is Errol Flynn. “He had changed so much. His eyes were so sad. I had stared into them in enough movies to know his spirit was gone. They used to be full of mischief, with little brown and green glints. They were totally different. I didn’t recognize the person behind the eyes.”

The story that had begun so optimistically for these two beautiful people on the set of Captain Blood would bring, to this day, loneliness for Olivia and tragedy for Errol. To tie in the physical evidence of Flynn’s private hell, Matzen includes two photos (pages 172 and 191) taken toward the end of his life. They show his deterioration, the puffy face, the lifeless eyes, the hunched back.

The story that had begun so optimistically for these two beautiful people on the set of Captain Blood would bring, to this day, loneliness for Olivia and tragedy for Errol. To tie in the physical evidence of Flynn’s private hell, Matzen includes two photos (pages 172 and 191) taken toward the end of his life. They show his deterioration, the puffy face, the lifeless eyes, the hunched back.

Rightly so, however, the last picture in Errol & Olivia is of the two stars, separate yet together, a beaming Olivia beside a larger-than-life photo of Errol from, it appears, around 1939. He has that familiar winking smile and, with a stretch of the imagination, he seems to be looking at her. In 1976 de Havilland had gone to New York to help celebrate the re-release of some Warner Bros. films from that Golden Age of which they both had been a part.