“Never dare to deceive two women.”

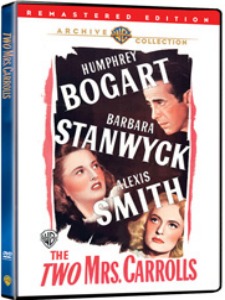

The Two Mrs. Carrolls ranks right up there with Conflict or, rather, down there, as one of the worst films Humphrey Bogart ever made. Various sources provide different titles for this “honor,” even confusion regarding the movie Humphrey Bogart himself singled out, but The Two Mrs. Carrolls, by all means, is in the running. Filmed in 1945, it was not released until 1947. Hum-m-m— What could that suggest? It’s likely everyone knew, beginning with Jack Warner and surely the stars. Director Peter Godfrey, who apparently gave his actor little guidance or constraint, had to know.

And there’s another component gone awry. Good film scores help good films be even better, but from the beginning the background music here is anything but helpful; far from subtle, it’s over the top, portentous, anticipatory, pseudo-dramatic beyond words. Franz Waxman, it’s true, has a tendency at times to be a bit overly intense, too Teutonic, but he must’ve sensed he was aboard a sinking ship and thought his talents could save things. Well, he couldn’t—and didn’t—save the film: the water came in anyway.

First, to go back a bit. This is one of two movies in the mid-1940s—the other being Conflict—that cast Humphrey Bogart as a wife murderer. The Two Mrs. Carrolls begins on a fishing trip in Scotland—in the woods—then in a cave—a resonant cave at that. On a casual, innocently spoken word, “death” echoes throughout the cave, and Humphrey Bogart gets a crazed wrinkle in his eyes, the seed of an idea. Already Franz Waxman’s heavy music is underlining this ominous moment and trying to foreshadow the disquiet to come. Unnecessarily. There’s plenty of time for that.

First, to go back a bit. This is one of two movies in the mid-1940s—the other being Conflict—that cast Humphrey Bogart as a wife murderer. The Two Mrs. Carrolls begins on a fishing trip in Scotland—in the woods—then in a cave—a resonant cave at that. On a casual, innocently spoken word, “death” echoes throughout the cave, and Humphrey Bogart gets a crazed wrinkle in his eyes, the seed of an idea. Already Franz Waxman’s heavy music is underlining this ominous moment and trying to foreshadow the disquiet to come. Unnecessarily. There’s plenty of time for that.

After a two-week romance and as she huddles in the cave from a rainstorm, Sally (Barbara Stanwyck) discovers that Geoffrey Carroll (Humphrey Bogart) is married. “Why didn’t you tell me?” she asks. Duh! The first clue that the dialogue will be wanting. Sally says she can’t live this way and leaves. Geoffrey returns to his apartment outside London, and now we meet his daughter, Beatrice (Ann Carter), a precocious ten-year-old who converses as if she were eighteen, similar to the obnoxious abrasiveness of Patty McCormack in The Bad Seed.

Carroll is a painter and he and the child admire his latest finished canvas, a portrait of his wife titled “The Angel of Death.” Bea suggests it’s one of his best, and in that mature air, says, “I know you’ll do whatever is best for mother”—mom has been sick—spoken almost sarcastically, as though she knows what daddy is up to, though there’s never any later evidence that she does.

Carroll is a painter and he and the child admire his latest finished canvas, a portrait of his wife titled “The Angel of Death.” Bea suggests it’s one of his best, and in that mature air, says, “I know you’ll do whatever is best for mother”—mom has been sick—spoken almost sarcastically, as though she knows what daddy is up to, though there’s never any later evidence that she does.

Daddy, indeed, is up to something—with his glasses of milk. He’s seen pouring the warm liquid from a sauce pan into a glass and getting Bea out of the room on the pretext of putting away his coat and hat. The real clues are in his hesitations, his wary glances and his long stance before he enters his wife’s room—a wife never seen. He’s never seen putting anything in the drink; earlier he had been to a chemist’s shop in London, making an unidentified purchase.

In the next scene, Charles Pennington (Patrick O’Moore, in one of the few natural performances in the film) arrives at Geoffrey’s new suburban home—quite a step up, as he must be selling some of those paintings—and asks to see Mrs. Carroll. Bea, mature as ever, now with long hair instead of pigtails to suggest she’s older, informs him, and the viewer for the first time, that her mother died two years ago. Shortly after, the second Mrs. Carroll comes in the room and embraces her former suitor—and, yes indeed, it’s Sally.

Pennington had admired “The Angel of Death” and was told by Bea that “father says it’s representational.” Later he asks Sally, “How old is she—forty-five or fifty?” So maybe the producers were aware of Carter’s miscasting and were attempting to justify the disparity between the child and her adult discourses.

Pennington announces that some friends will be arriving—Mrs. Latham (Isobel Elsom, whose career spanned fifty years, beginning in 1916) and her daughter Cecily (Alexis Smith, a veteran of at least four Errol Flynn flicks, most notably Gentleman Jim). The garden tea that ensues among the Carrolls and their guests features some of the strangest, most uncomfortable, unnatural dialogue, with barbs, drawing room repartee and innuendo. The “best” line, if that accolade applies here!, comes when Cecily asks to see some of Geoffrey’s paintings. He replies that, yes, he would show them to her—“with the greatest reluctance.”