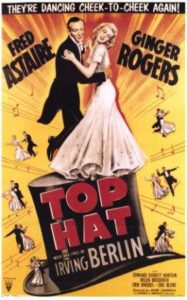

“When Top Hat is letting Mr. Astaire perform his incomparable magic or teaming him with the . . . dexterous Miss Rogers, it is providing the most urbane fun that you will find anywhere on the screen.” —— Andre Sennwald, The New York Times of August 30, 1935

An incident related by a friend is apropos to the movie at hand. It seems his grandchildren—a boy of ten and a girl of thirteen, brought up on space epics, special effects, rapid editing, fast action and loud noises—were complaining about those old movies from their grandfather’s time, old black and white movies, that they were old-fashioned, boring, quaint and silly. No way as good as today’s movies.

The criticisms from the little ones had come during the evening meal, so my friend waited until later. “Let me show you something,” he said as he put a DVD in his player. The resultant image was of a dancing couple, he in tie and tails, she in a white, flowing gown. Her dress could only be white because it clearly wasn’t black and this was B&W, one of those old pictures from eons ago.

The two children, my friend recounted, were soon mesmerized. They confided their amazement—the grace, elegance, precision of the two dancers, perhaps their charisma if the kids had known the word, and the spontaneity, though they were ignorant of the endless planning and rehearsals that had proceeded each dance number. And that music! Sparkling and fresh, unpretentious, singable—why, one of the melodies the boy hummed all day—and the words, they, too, were straightforward, so simple as to be poetic, teasingly romantic and they made sense.

“I didn’t know, back then,” the girl said, who had been taking ballet for three years, “people could dance like that. I didn’t know they had—well, talent back then.” And more talent, her grandfather thought but didn’t express, than a half dozen of the so-called “singers” and “stars” of today.

My friend said later that the film was Swing Time (1936), the sixth musical starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, dancing and singing their hearts out, of course.

During their first two movies, Astaire didn’t especially take to Rogers and, besides, he didn’t wish to be associated with a single partner. The couple made nine musicals for RKO between 1933 and 1939: Flying Down to Rio, The Gay Divorcée, Roberta, Top Hat, Follow the Fleet, Swing Time, Shall We Dance?, Carefree and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle. These were lean years for the studio and the Astaire/Rogers films were among the few financial successes that saved RKO from bankruptcy. The only other film the couple made together was The Barkleys of Broadway, for M-G-M, in 1949.

During their first two movies, Astaire didn’t especially take to Rogers and, besides, he didn’t wish to be associated with a single partner. The couple made nine musicals for RKO between 1933 and 1939: Flying Down to Rio, The Gay Divorcée, Roberta, Top Hat, Follow the Fleet, Swing Time, Shall We Dance?, Carefree and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle. These were lean years for the studio and the Astaire/Rogers films were among the few financial successes that saved RKO from bankruptcy. The only other film the couple made together was The Barkleys of Broadway, for M-G-M, in 1949.

Astaire, undoubtedly the better dancer of the two, is, after all, one of the great dancers of the cinema, admired by Mikhail Baryshnikov, a spokesman from another dancing genre. Astaire’s greatest male dancing screen rival is Gene Kelly. They are quite different on their feet, Astaire more vertically graceful, Kelly more the acrobat. Perhaps Kelly himself summed it up best: “I was the Marlon Brando of dancers and he was the Cary Grant.” This despite that famous comment by a studio talent scout regarding Astaire’s first screen test: “Can’t act, can’t sing, balding, can dance a little.”

Ginger Rogers, whose film career began with bit parts, gradually improved as a dancer, much aided by her instinctive ability to move in perfect sync with Astaire. Despite their effortless appearance, she complained on one occasion, “Just try and keep up with [Fred’s] feet sometime! Try and look graceful while thinking where your right hand should be, and how your head should be held, and which foot you end the next eight bars on, and whether you’re near enough to the steps to leap up six of them backward without looking.”

Ginger Rogers, whose film career began with bit parts, gradually improved as a dancer, much aided by her instinctive ability to move in perfect sync with Astaire. Despite their effortless appearance, she complained on one occasion, “Just try and keep up with [Fred’s] feet sometime! Try and look graceful while thinking where your right hand should be, and how your head should be held, and which foot you end the next eight bars on, and whether you’re near enough to the steps to leap up six of them backward without looking.”

As Katharine Hepburn said, Rogers gave Astaire sex appeal, he gave her class.

The Broadway musical, in a deep slump during the Great Depression, had a rebirth with the advent of motion picture sound in 1929, and everybody moved to Hollywood, including such first-class songwriters as Jerome Kern, George and Ira Gershwin and Irving Berlin. A glut of movie musicals followed, so many, in fact, that by the late ’30s, this new, fertile ground had been over-planted and the public had tired of the singing, the dancing and the often convoluted choreography.

In the early ’30s, while still in good health, the Hollywood musical was exemplified, first, by the films of Busby Berkeley and his complicated spectacles—girls atop gigantic pyramids with unfolding curtains of silk, girls forming geometric designs in enormous pools of water, girls descending staircases, girls with cameras passing between their spread legs. Berkeley directed only these extravaganzas, which were dropped in like so many tossed rose petals without any relation to the plot at hand. The film itself would be directed by someone else.

In the early ’30s, while still in good health, the Hollywood musical was exemplified, first, by the films of Busby Berkeley and his complicated spectacles—girls atop gigantic pyramids with unfolding curtains of silk, girls forming geometric designs in enormous pools of water, girls descending staircases, girls with cameras passing between their spread legs. Berkeley directed only these extravaganzas, which were dropped in like so many tossed rose petals without any relation to the plot at hand. The film itself would be directed by someone else.

The Astaire/Rogers films introduced the second major change in the Hollywood musical. In their kind of movies, the hundreds of girls and over-choreographed sequences were gone and, now, amazingly, and most importantly, the musical numbers were integrated into the plot. Astaire, ever the perfectionist and never shy about demanding the thirtieth take on a number, insisted the dancer/dancers be the center of attention—full body view, no esoteric camera technique, as few cuts as possible, no close-ups of faces, feet, certainly no views of a watching audience.

Before Astaire and Rogers had finished their last film of the thirties, and the last for RKO, the musical, period, was losing its appeal, and the Hollywood genre would not fully return until the mid-’50s.

Top Hat, the fourth of the Astaire/Rogers films, was the second highest-grossing film of 1935, surpassed only by M-G-M’s Mutiny on the Bounty. The musical was nominated (unsuccessfully) for four Oscars—Picture, Art Direction, Dance Direction (the short-lived category lasted from 1935 to 1937) and Song, Irving Berlin’s “Cheek to Cheek.”

Top Hat, the fourth of the Astaire/Rogers films, was the second highest-grossing film of 1935, surpassed only by M-G-M’s Mutiny on the Bounty. The musical was nominated (unsuccessfully) for four Oscars—Picture, Art Direction, Dance Direction (the short-lived category lasted from 1935 to 1937) and Song, Irving Berlin’s “Cheek to Cheek.”

On the set, Astaire first met Berlin, who was writing all the songs and words for the movie. The two men became fast friends until Astaire’s death in 1987. Composer Max Steiner, three years after his milestone score for King Kong, was the music director.

Although Astaire/Rogers danced to more numbers in Top Hat than in any of their other musicals, a few of Berlin’s songs were cut, including “Get Thee Behind Me, Satan,” “You’re the Cause” and “Wild About You.” The tunes either over-extended the film’s length or were inappropriate for the plot.

The plot is simplicity itself, clichéd, yes, but streamlined to facilitate the musical numbers—and, at the same time, to have the songs complement the story. Dancer Jerry Travers (Astaire) arrives in London to meet with his producer, Horace Hardwick (Edward Everett Horton). Already, fun is poked at English civility in a gentlemen’s club, where the least sound—the accidental clinking of two wine glasses or talking above the softest whisper—causes irate looks from the stony members sitting about. Before leaving the Thackeray Club, Jerry can’t resist the temptation. At the doorway to the sitting room, he applies a brief, loud tap-dance rhythm to the hard floor, and is quickly ushered out by an embarrassed Hardwick.

The plot is simplicity itself, clichéd, yes, but streamlined to facilitate the musical numbers—and, at the same time, to have the songs complement the story. Dancer Jerry Travers (Astaire) arrives in London to meet with his producer, Horace Hardwick (Edward Everett Horton). Already, fun is poked at English civility in a gentlemen’s club, where the least sound—the accidental clinking of two wine glasses or talking above the softest whisper—causes irate looks from the stony members sitting about. Before leaving the Thackeray Club, Jerry can’t resist the temptation. At the doorway to the sitting room, he applies a brief, loud tap-dance rhythm to the hard floor, and is quickly ushered out by an embarrassed Hardwick.

Jerry causes another disturbance in the hotel room where, later, he is conferring with Hardwick. After throwing sand on the hard floor, he dances and taps his way around the room, singing “No Strings” and annoying the young lady, Dale Tremont (Rogers), in the room below. She calls the hotel desk to complain. The clerk calls Jerry’s room and informs Hardwick, who answers the phone, that “a lady” is on her way up. When Dale arrives, Jerry is immediately smitten and immediately begins to pursue her.

Then follows, the plot cliché—but a comic, enjoyable one—of mistaken identity. Dale assumes Jerry is Horace. A second mistaken identity occurs when Dale’s friend Madge (Helen Broderick) thinks her husband—the real Horace—is seeing Dale behind her back when Dale complains to her that “Horace” had chased her around a park. Madge takes a nonchalant, permissive approach to the whole matter: “I didn’t know Horace was capable of that much activity.”

Then follows, the plot cliché—but a comic, enjoyable one—of mistaken identity. Dale assumes Jerry is Horace. A second mistaken identity occurs when Dale’s friend Madge (Helen Broderick) thinks her husband—the real Horace—is seeing Dale behind her back when Dale complains to her that “Horace” had chased her around a park. Madge takes a nonchalant, permissive approach to the whole matter: “I didn’t know Horace was capable of that much activity.”

Dale takes a hansom through London and assumes, by the cabby’s accent, that he is a Cockney, only to learn, by the foot taps on the roof, that he is Jerry. When the two are horseback riding in the park, they seek shelter from the rain in a gazebo. Here, in the only dance/song routine in the movie where Astaire is out of evening attire, he sings “Isn’t This a Lovely Day?”—solo at first, then Dale joins his dancing, gradually becoming more involved. She briefly sings the song, a cappella.

Jerry’s show is a big success in London, illustrated with “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails.” Here Astaire dances with thirty or forty men, all in tuxedos, then, one by one, he “shoots” each into a crouched position, with his cane serving as an imaginary rifle. (Astaire was so frustrated by his mistakes, and the number of takes, that he broke twelve canes before he was satisfied with a take—when he was on the last prop cane.)

Jerry’s show is a big success in London, illustrated with “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails.” Here Astaire dances with thirty or forty men, all in tuxedos, then, one by one, he “shoots” each into a crouched position, with his cane serving as an imaginary rifle. (Astaire was so frustrated by his mistakes, and the number of takes, that he broke twelve canes before he was satisfied with a take—when he was on the last prop cane.)

Intertwined with all this, there’s the expected villain, Alberto Beddini (Erik Rhodes), an effeminate, now belligerent, Italian fashion designer who is out to get Jerry for stealing Dale. “For the women the kiss,” he repeatedly says, “for the men the sword!” Alberto and Jerry eventually confront one another, but resolve their differences.

The most famous number, clearly the best-remembered song in the movie, and one of Berlin’s best-ever, is “Cheek to Cheek.” The scene begins unassumingly, the melody introduced in the score as Jerry and Dale are waltzing, along with other couples. Astaire sings a few verses as they dance. Then, with a camera cut, the couple are miraculously alone on a marble-floored patio, their dancing gradually more physical—never frantic or frenzied, never ungraceful—as he dips her slightly, she does a side-by-side imitation of his moves, then a bit of tap-dancing before he half-lifts her in gown-flowing whirls and, later, in higher whirls and, finally, an extravagant dip to end.

The most famous number, clearly the best-remembered song in the movie, and one of Berlin’s best-ever, is “Cheek to Cheek.” The scene begins unassumingly, the melody introduced in the score as Jerry and Dale are waltzing, along with other couples. Astaire sings a few verses as they dance. Then, with a camera cut, the couple are miraculously alone on a marble-floored patio, their dancing gradually more physical—never frantic or frenzied, never ungraceful—as he dips her slightly, she does a side-by-side imitation of his moves, then a bit of tap-dancing before he half-lifts her in gown-flowing whirls and, later, in higher whirls and, finally, an extravagant dip to end.

(A famous incident occurred with the ostrich-feathered blue gown Rogers wears for this dance. Astaire and director Mark Sandrich, who directed five of these musicals, felt the gown was impractical. Rogers insisted she wear it. In the first take, the feathers started to come off. Although a halt was called and much time was spent on sewing each feather securely in place, in the released picture occasional feather parts can be see floating to the floor.)

The plot of Top Hat becomes further confusing. Dale still believes Jerry is Horace, and is disgusted when he, this married man, proposes marriage. She marries Alberto instead—or so she thinks. Horace’s officious English valet (Eric Blore) disguises himself as a priest and performs the ceremony. Blore is best known as another valet, Warren William’s in the Lone Wolf series.

The plot of Top Hat becomes further confusing. Dale still believes Jerry is Horace, and is disgusted when he, this married man, proposes marriage. She marries Alberto instead—or so she thinks. Horace’s officious English valet (Eric Blore) disguises himself as a priest and performs the ceremony. Blore is best known as another valet, Warren William’s in the Lone Wolf series.

Now, at the last, Jerry is able to convince Dale that he is not Horace and single. The couple marry and dance in the final, big-number show-stopper, a fantasy version of the Lido of Venice, with terraces and three levels of dance floors, and surrounded by an enormous tank of black-dyed water. This sequence, deemed too long by preview audiences, was cut, eliminating scenes with Donald Meek and Florence Roberts. Jerry and Dale dance to “The Piccolino,” with a bevy of dancers. “The Piccolino” was, perhaps, Berlin’s answer to Con Conrad’s “The Continental,” to which Astaire and Rogers had danced in The Gay Divorcée (1934), but here, for once, Berlin comes out second best to Conrad.

In 1897, you’ll remember, a writer for the New York newspaper The Sun had responded to a question from eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanion that, “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus.” If a later journalists, now turning the tables, were to ask the same woman, alive when Top Hat was released (she died in 1971), “Was there ever any grace, charm and, above all, talent in those old B&W movies of eons ago?,” she could honestly reply that, yes, Mr. Reporter, there was.

In 1897, you’ll remember, a writer for the New York newspaper The Sun had responded to a question from eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanion that, “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus.” If a later journalists, now turning the tables, were to ask the same woman, alive when Top Hat was released (she died in 1971), “Was there ever any grace, charm and, above all, talent in those old B&W movies of eons ago?,” she could honestly reply that, yes, Mr. Reporter, there was.