“If there was a law they was workin’ with, maybe we could take it, but it ain’t the law. They’re workin’ away our spirits, tryin’ to make us cringe and crawl, takin’ away our decency.” —— Tom Joad (Henry Fonda)

A man walks along an empty Oklahoma highway. The black-and-white screen is somehow heavy with the dark, though it is daylight; heavy, too, with loneliness, and maybe, to those who have seen the film and know what’s coming, heavy with a sense of despair. The man is Tom Joad, freshly out of prison on parole, returning to his parents’ farm. He receives a lift from a suspicious truck driver who sees him as shifty and is dropped off near the farm.

By all those involved, The Grapes of Wrath was planned, begun and completed with much enthusiasm and an awareness that in the making was something of an American masterpiece, both as a film, if different and harsher than any before it, and as a nonpartisan commentary on the failings of the American dream, though certain political parties saw it otherwise—as a liberal diatribe, pro-union, even communistic. Its director, John Ford, at the time a liberal and supported of Roosevelt’s New Deal, was stubborn and contrary enough in his political leanings to say otherwise if someone accused him directly of one particular affiliation.

“I was sympathetic,” Ford said, “to the people like the Joads [who had fallen on hard times], and contributed a lot of money to them, but I was not interested in Grapes of Wrath as a social study.” On another occasion the director remarked: “ . . . and Darryl Zanuck had a good script on [the novel]. The whole thing appealed to me, being about simple people, and the story was similar to the famine in Ireland, when they threw the people off the land and left them wandering on the roads to starve.”

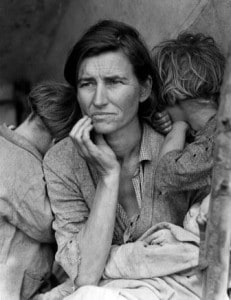

The Grapes of Wrath is a searing comment on the flight in the 1930s of the tenant farmers of the U.S. who fought not only the deprivations of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl in the Midwest—drought that destroyed their crops and winds that, literally, swept away their soil—but the land agents and banks who chased them off their farms. The film artistically, but never prettily, duplicates, perhaps intentionally, the haunting b&w photographs of Dorothea Lange (note her “Migrant Mother” from 1936) and, lesser well known, those of Ben Shahn and Arthur Rothstein, both working for the Farm Security Administration during the Depression. How insipid these—the movie and the photographs—would be in color!

The Grapes of Wrath is a searing comment on the flight in the 1930s of the tenant farmers of the U.S. who fought not only the deprivations of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl in the Midwest—drought that destroyed their crops and winds that, literally, swept away their soil—but the land agents and banks who chased them off their farms. The film artistically, but never prettily, duplicates, perhaps intentionally, the haunting b&w photographs of Dorothea Lange (note her “Migrant Mother” from 1936) and, lesser well known, those of Ben Shahn and Arthur Rothstein, both working for the Farm Security Administration during the Depression. How insipid these—the movie and the photographs—would be in color!

If viewers should think the film exaggerates the truth, making what happened worse than it was, then they should think again.

Two other men seemed to drive the film beyond just the vision of John Ford. Twentieth Century-Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck saw enough potential in John Steinbeck’s 1939 Pulitzer-winning novel to pay the enormous sum of $100,000 for the film rights. Henry Fonda knew Tom Joad was the role of a lifetime, but he also knew that signing a seven-year contract with any studio would sacrifice his artistic freedom. And Zanuck’s first stipulation before any signing was an eight-picture deal. But sign Fonda did. The role was the first of two Best Actor Oscar nominations for him, winning only with the second, forty-one years later; On Golden Pond was partly a sentimental nod, as most of Hollywood knew the actor was in poor health. That Fonda didn’t win—he was nominated—for Grapes of Wrath leaves much room for discussion (more later).

For all that was going for the film, and that would make it a classic, there was just as much going against its being made and, later, its being shown. The Associated Farmers of California called for a boycott, as the film reflected unfavorably on the growers. Steinbeck received death threats for “telling it like it was,” and both he and Ford were investigated by Congress during the House Un-American Activities Committee for the pro-union aspects of the film. At the time, the novel was purged from a number of city libraries and not allowed in the library of Steinbeck’s hometown of Salinas, California, until the 1990s. All this because Grapes of Wrath exposed the tragic flight of farmers fleeing the Dust Bowl, in particular from Oklahoma, and the abuse and injustices they received along the way, as they traversed Texas, New Mexico and Arizona to the expected Promised Land of California.

For all that was going for the film, and that would make it a classic, there was just as much going against its being made and, later, its being shown. The Associated Farmers of California called for a boycott, as the film reflected unfavorably on the growers. Steinbeck received death threats for “telling it like it was,” and both he and Ford were investigated by Congress during the House Un-American Activities Committee for the pro-union aspects of the film. At the time, the novel was purged from a number of city libraries and not allowed in the library of Steinbeck’s hometown of Salinas, California, until the 1990s. All this because Grapes of Wrath exposed the tragic flight of farmers fleeing the Dust Bowl, in particular from Oklahoma, and the abuse and injustices they received along the way, as they traversed Texas, New Mexico and Arizona to the expected Promised Land of California.

As a filmmaker, Zanuck was ever the perfectionist and crusader against prejudice and injustice, in Grapes as well as in Gentleman’s Agreement, How Green Was My Valley and Island in the Sun. And to make sure Grapes of Wrath would, indeed, “tell it like it was,” he had a secret team investigate the camps of the migrants. Was the squalor and abuse as wretched as depicted in Steinbeck’s novel? He was surprised to learn that it was worse.

As Tom (Fonda) leaves the road and steps into a field, he finds a man sitting under a tree. Jim Casy (John Carradine), an ex-preacher, recognizes Tom and tells him he has “lost the spirit.” The two eventually arrive at the dilapidated Joad family farm house, in a wind storm appropriately enough. “Ma? Ma?” Tom calls out in the dark. He finds only a neighbor, Muley (John Qualen), who is hiding from the original deed holders who are forcing the farmers from home and land, specifically bulldozing their houses. He relates his own experience to the two men.

As Tom (Fonda) leaves the road and steps into a field, he finds a man sitting under a tree. Jim Casy (John Carradine), an ex-preacher, recognizes Tom and tells him he has “lost the spirit.” The two eventually arrive at the dilapidated Joad family farm house, in a wind storm appropriately enough. “Ma? Ma?” Tom calls out in the dark. He finds only a neighbor, Muley (John Qualen), who is hiding from the original deed holders who are forcing the farmers from home and land, specifically bulldozing their houses. He relates his own experience to the two men.

Tom and Casy find the Joad family living on Tom’s Uncle John’s (Frank Darien) farm. The Joads include its matriarch, Ma (Jane Darwell), Pa (Russell Simpson), Grandpa (Charley Grapewin) and Grandma (Zeffie Tilbury). To escape the officials who are coming in the morning to make sure the land is vacated, the Joads and other members of the family leave for California at daybreak. What household items they can take are packed in, on or roped to a 1926 Hudson sedan made over as a truck. Casy decides to go with them.

The long trip on Highway 66 is hard on the travelers, and Grandpa dies alongside the road and is buried there. Nearly unconscious on his back, his right hand clutches a clump of dirt and drops it on the left hand of Pa, who is bent over him with words of comfort: “You’re just tired.” It is possibly symbolic, the father passing, finally, the reigns of the family to his son, and, maybe as further symbolism, as protector of the land. Grandpa must have known, as does the whole family, that Ma Joad is clearly their head.

The long trip on Highway 66 is hard on the travelers, and Grandpa dies alongside the road and is buried there. Nearly unconscious on his back, his right hand clutches a clump of dirt and drops it on the left hand of Pa, who is bent over him with words of comfort: “You’re just tired.” It is possibly symbolic, the father passing, finally, the reigns of the family to his son, and, maybe as further symbolism, as protector of the land. Grandpa must have known, as does the whole family, that Ma Joad is clearly their head.

Later Grandma will die as well, with Ma stroking her brow.

In a migrant camp for the night, another itinerant, returning from California, crushes the Joads’ hopes of a better life. He says the handbills they have been given, offering eight hundred jobs in California, are meaningless by now. Thousands have been passed out, thousands read, so “two or three thousand start west.” The jobs are all gone by now, even if they were there in the first place. The man says he’d rather starve at home than starve in California.

At the next camp, the Keene Ranch, the Joads find that over-priced food in the company store has contributed to a planned strike by the migrants. Tom goes to a meeting in the woods, but the camp guards discover it and Casy is killed. Tom accidentally kills one of the guards in his defense of Casy, incurring a cheek wound.

At the next camp, the Keene Ranch, the Joads find that over-priced food in the company store has contributed to a planned strike by the migrants. Tom goes to a meeting in the woods, but the camp guards discover it and Casy is killed. Tom accidentally kills one of the guards in his defense of Casy, incurring a cheek wound.

Realizing the injury will identify him, Tom hides under the mattresses in the truck as the Joads quickly leave the camp, traveling to the next one, run by the Department of Agriculture. Amazing, the facilities include indoor toilets and showers, which the Joad children have never seen, schools and even a Saturday night dance. Maybe things are looking up, the Joads think.

Later, when Tom sees some deputies checking the license of the truck, he knows it won’t be long before they will return with a warrant. He must leave and says farewell to Ma in the most famous lines from the film:

“Well, maybe it’s like Casy says. A fella ain’t got a soul of his own, just a little piece of a big soul, the one big soul that belongs to ever’body. Then . . . then it don’t matter. I’ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be ever’where—wherever you can look. Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready, an’ when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise, and livin’ in the houses they build, I’ll be there, too.”

As the film had begun, Tom is once again on his own, walking alone, now a distant figure against a brilliant sunrise.

The remaining Joads are heading out once again, Ma driving the old truck. Seen through the windshield, as so often before, Ma and Pa are talking. Pa tells her she’s the one who “keeps us goin’. I ain’t no good no more, and I know it.”

The remaining Joads are heading out once again, Ma driving the old truck. Seen through the windshield, as so often before, Ma and Pa are talking. Pa tells her she’s the one who “keeps us goin’. I ain’t no good no more, and I know it.”

Ma says, “Rich fellas come and they die, and their kids ain’t no good and they die out, be we keep a-comin’. We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out, they can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever, Pa, cause we’re the people.”

Author Steinbeck was unexpectedly pleased with Nunnally Johnson’s screenplay, well aware of the distortion and desecration Hollywood writers so often inflict on literary works, both masterpieces and otherwise. Johnson remained true to the spirit of the novel, of one mind with both Ford and Zanuck in their fervor, limited to condensing, rearranging scenes and sometimes switching the speakers of the dialogue. Granted, the opening is a new creation. The language, of course, had to be toned down and any direct reference to communism deleted. Also, impossible at least in the 1940s, was filming the novel’s ending, about a stillborn baby floating down a stream and its mother offering the milk of her breasts to a dying man.

In one added scene, which impressed Steinbeck and which he sanctioned, the Joads stop at a roadside diner, and Pa wishes to purchase a loaf of bread, since, he says, Grandma has no teeth (though earlier she is seen eating with teeth). Pa has allotted only ten cents for such a purchase, for, as he says, they have a thousand uncertain miles to go. The annoyed waitress (Gloria Roy) says the diner isn’t a grocery store, that, anyway, a loaf would cost fifteen cents. The chef says to give him the loaf—it’s yesterday’s bread. Pa still places ten cents on the counter for the loaf. When he asks the price of two “striped” candies for the two kids beside him, the waitress, after hesitating, replies they’re two for a penny. Pa says he’ll take two. After the Joads leave, a truck driver at the bar reminds the waitress, who has undergone something of an incredible conversion in a matter of minutes, that she well knows the candy is a nickel apiece.

In one added scene, which impressed Steinbeck and which he sanctioned, the Joads stop at a roadside diner, and Pa wishes to purchase a loaf of bread, since, he says, Grandma has no teeth (though earlier she is seen eating with teeth). Pa has allotted only ten cents for such a purchase, for, as he says, they have a thousand uncertain miles to go. The annoyed waitress (Gloria Roy) says the diner isn’t a grocery store, that, anyway, a loaf would cost fifteen cents. The chef says to give him the loaf—it’s yesterday’s bread. Pa still places ten cents on the counter for the loaf. When he asks the price of two “striped” candies for the two kids beside him, the waitress, after hesitating, replies they’re two for a penny. Pa says he’ll take two. After the Joads leave, a truck driver at the bar reminds the waitress, who has undergone something of an incredible conversion in a matter of minutes, that she well knows the candy is a nickel apiece.

Fonda’s cool- and cold-eyed Tom Joad is a strong, determined, independent defender of the Common Man, often insolent or belligerent, as toward a man at a filling station who wants to know if the Okies can pay for the gas. Tom is, after all, a bitter man, a migrant, poor, dispossessed and on the run. The austerity of the character is somewhat related, some have said, to the actor’s own personality, for Tom Joad is, in many respects, Henry Fonda.

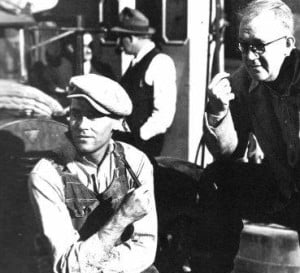

It’s true that the uniformly great acting by all involved, especially Fonda, Darwell and Carradine, carries the picture along. But it is the b&w cinematography of Gregg Toland—his first film with John Ford—that underlines the characters’ drama, their anguish, their despair and, in the end, their hope of an eventual triumph, that makes Grapes of Wrath such an intense and tragic yet memorable film.

It’s true that the uniformly great acting by all involved, especially Fonda, Darwell and Carradine, carries the picture along. But it is the b&w cinematography of Gregg Toland—his first film with John Ford—that underlines the characters’ drama, their anguish, their despair and, in the end, their hope of an eventual triumph, that makes Grapes of Wrath such an intense and tragic yet memorable film.

The photography is sharp-edged and natural, no diffusion on the camera to soften the impact, no sentimentalizing to make the horror more palatable. Here is some of the darkest photography ever seen on screen, with much night shooting, a number of scenes illuminated only by indirect light from outside a dark room or a lantern in a tent or a single candle, albeit a small electric light concealed in the palm of a hand. This in the best tradition of film noir, though with a totally different feel and inference in the shadows and streaks of white light.

Early in the film, Muley’s flashback telling of his farm’s destruction delineates the kind of powerful photography—never drawing attention to itself—that permeates the film. The first camera shot shows Muley and his family standing before their home, then pans down to their long shadows on the ground as the bulldozer smashes the structure and moves on, presumably to the next house; a cut, and the second camera shot returns to the family, then pans down again to their shadows. It is perhaps curious why this scene wasn’t done in a single, uncut shot.

Further, during this scene there is no support from Alfred Newman’s score. Here, as in long stretches of celluloid in Grapes, the unnoticed absence of music is actually more effective than had music been present; adding music to these visuals and to the emotions on screen, already strong enough in themselves, would only detract. Ford often complained that the music directors added more score to his films than he wanted, as he specifically said about The Searchers. As for “too much talking,” he was known to tear pages from a script to tighten a scene, preferring to let the camera carry the meaning. Less music, less dialogue: these recall Ford’s solid foundation in his early days in silent films.

Further, during this scene there is no support from Alfred Newman’s score. Here, as in long stretches of celluloid in Grapes, the unnoticed absence of music is actually more effective than had music been present; adding music to these visuals and to the emotions on screen, already strong enough in themselves, would only detract. Ford often complained that the music directors added more score to his films than he wanted, as he specifically said about The Searchers. As for “too much talking,” he was known to tear pages from a script to tighten a scene, preferring to let the camera carry the meaning. Less music, less dialogue: these recall Ford’s solid foundation in his early days in silent films.

The enormous cast of Grapes of Wrath is populated with many supporting players, including some of Ford’s favorites: O. Z. Whitehead, Grant Mitchell, Dorris Bowdon, Ward Bond, Charles Middleton, Frank Faylen, Harry Cording and a number of child actors, including Darryl Hickman.

Postscript

In retrospect, 1940 is one of the more obvious years that can be re-examined relative to the Oscars, since time—and seventy-five years have elapsed, now—is always the best judge of quality and the staying power of anything, especially art. The following is only the opinions of this writer, opinions subject to any number of understandably justified challenges. The big error of this thinking, admitted, is that Academy voters in 1940 had no insight into the future that would provide the comparative perspective that allows us, now in 2015, to know the film and individual artist winners over time, and thereby make possible these hypothetical “adjustments” for a more equal distribution of merit.

No one ever said the Oscars are fair and objective, mainly on two counts—first, because of the swaying power of studio backing and, related, the undue influence of the popular, money-making films as a gauge of merit; and, second, because, as so many people have attested, different kinds of film genres—musicals, Westerns, comedies, historical dramas, adventures, et al.—are as dissimilar from one another as those proverbial oranges and apples, and cannot, in all fairness, be compared.

No one ever said the Oscars are fair and objective, mainly on two counts—first, because of the swaying power of studio backing and, related, the undue influence of the popular, money-making films as a gauge of merit; and, second, because, as so many people have attested, different kinds of film genres—musicals, Westerns, comedies, historical dramas, adventures, et al.—are as dissimilar from one another as those proverbial oranges and apples, and cannot, in all fairness, be compared.

Nothing can be done about the awarded Oscars—they are history—but what if——

Shocking statement Number One, perhaps? The Grapes of Wrath should have won the Best Picture Oscar. Its year, 1940, was one of the great years of filmdom, a little short of the “big one,” 1939, of course, but a respectable part of Hollywood’s Golden Age. It would be unfortunate to deny Alfred Hitchcock his only Best Picture win for Rebecca, though he would later be nominated Best Director for far better films (Notorious, Rear Window, Psycho), and for better, unnominated films (Shadow of a Doubt, Vertigo, North by Northwest). Again, Grapes and Rebecca are entirely different kinds of films, but if a gun-to-the-head comparison is mandated, then Grapes is the better film.

Another shocker? James Stewart should not have won Best Actor for The Philadelphia Story. For one thing, he would be far better and more deserving of an Oscar in Anatomy of a Murder, for which he was nominated but passed over in favor of Charlton Heston in Ben-Hur. In Grapes, Henry Fonda would never be better, not in Young Mr. Lincoln, The Lady Eve or 12 Angry Men. If the range of Fonda’s role is less nuanced than Stewart’s, it is the intensity, the assurance, that makes him superior to Stewart.

Another shocker? James Stewart should not have won Best Actor for The Philadelphia Story. For one thing, he would be far better and more deserving of an Oscar in Anatomy of a Murder, for which he was nominated but passed over in favor of Charlton Heston in Ben-Hur. In Grapes, Henry Fonda would never be better, not in Young Mr. Lincoln, The Lady Eve or 12 Angry Men. If the range of Fonda’s role is less nuanced than Stewart’s, it is the intensity, the assurance, that makes him superior to Stewart.

For a brief falling back in these attacks—no arguments here—John Ford deserves his directorial Oscar, as does Jane Darwell for Best Supporting Actress, her only real competition, perhaps, being the generally one-toned, though menacingly impressive, performance of Judith Anderson in Rebecca. Even Donald Ogden Stewart’s witty and biting dialogue in the Adapted Screenplay category for The Philadelphia Story is close enough a call against Nunnally Johnson’s for Grapes to be incontestable.

To resume the attack, now on a big omission, is Gregg Toland’s failure to even receive a nomination for Best B&W Cinematography for Grapes. Even though, yes, these were the days of Hollywood’s greatest cinematographers and he was up against, in 1940, among others, Joseph Ruttenberg, Ernest Haller, James Wong Howe and Joseph Valentine, his absence from the ballot is unforgivable—the Academy at its worst. Toland, however, was nominated that year for The Long Voyage Home, also directed by Ford, so maybe the Academy thought one nomination for him was enough. The winner in the category was George Barnes for Rebecca. Among those nominated, no complaints.

The lack of a nomination for Newman’s score for Grapes deserves no criticism, because, when not often absent, the music, when heard, mainly consists of variations on “Red River Valley.” Not much of an “original” score here. The complaint lies in the Academy’s persistence, since 1936 and enduring until 1984, in having three unnecessary music categories and an overabundance of nominations, some years as many as seventeen films in one category.

In 1940, there were thirty-five nominations among the categories of song, score and original score. Any distinction between the last two is inexplicable and, really, nonexistent. Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score for The Sea Hawk and Newman’s for The Mark of Zorro, split between the two classifications, are both swashbucklers and totally original, just as, again split, are Newman’s Tin Pan Alley and the three-member team who scored Pinocchio, the winners in their categories, Score and Original Score, respectively.

Just some musings, of no count, perhaps.