Master of Women’s Hearts . . . Conqueror of a New World.

Captain from Castile was made in the twilight years of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Its making, unfortunately, bridged the time from the purchase of the screen rights to Samuel Shellabarger’s novel in late 1944, when movie attendance was at a record high, to the premiere, Christmas 1947, by which time theater attendance had fallen drastically.

The film ended up costing much more than the average 20th Century-Fox endeavor of the time—over $4,500,000—and the studio would not recoup its investment. Of small importance now, perhaps, to movie-watching devotees, and especially to admirers of this brilliant, flashy extravaganza.

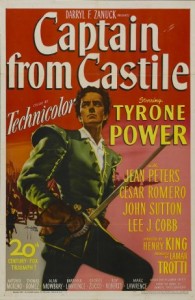

The film was intended from the start for Tyrone Power, and it suits him admirably. Considerable credit goes to Henry King, who had directed the star in at least eleven films, from Lloyd’s of London in 1936 to The Sun Also Rises in 1957, his next-to-last film. The two men combined their talents in another Shellabarger historical novel, Prince of Foxes, with less success.

The role of his romantic lead, however, was not at first secured. Linda Darnell, who had starred in a number of Power films including, most notably, The Mark of Zorro, was originally scheduled. Studio head Darryl Zanuck was momentarily distracted by the new rage, Jennifer Jones. When Jones eventually became unavailable, and in the meantime Darnell as well, he made his selection after viewing a screen test by a young Ohio State University student. Jean Peters had won a popularity contest and would, in the future, star in Three Coins in the Fountain and A Man Called Peter before retiring and becoming the second wife of Howard Hughes.

Shellabarger’s sprawling historical novel of two continents was something of a problem to summarize in a serviceable script, much like Hervey Allen’s twice-as-long Anthony Adverse, which Warner Bros. had turned into an equally long epic. Unlike the 1936 WB film, which had been done entirely on sets, whether Europe, Africa or Cuba, Captain from Castile was partially filmed in Mexico. The cast and crew spent four months in four or five luscious, though remote locations before returning to Hollywood for a month of interiors. While in Mexico, some interiors were shot in both a real sixteenth-century home and an especially built Aztec temple.

The transfer from page to screen was not entirely successful in either movie, as both seem to drag at times, the Shellabarger text even emitting a whiff of soap opera at times. But it’s the many pluses that have made Captain from Castile, by far, more watchable and enduring than Anthony Adverse, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s splendid, wall-to-wall score notwithstanding.

The transfer from page to screen was not entirely successful in either movie, as both seem to drag at times, the Shellabarger text even emitting a whiff of soap opera at times. But it’s the many pluses that have made Captain from Castile, by far, more watchable and enduring than Anthony Adverse, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s splendid, wall-to-wall score notwithstanding.

Captain from Castile remains one of the great swashbuckling epics, although there isn’t as much derring-do, per se, as typical of the genre. With its scope, variety of themes, larger-than-life characters and historical basis, it clearly qualifies as an epic. It is luxuriously photographed in Technicolor by Charles Clarke, who was taken off Miracle on 34th Street to replace an inadequate Arthur E. Arling, only one of the difficulties that beset the production.

There were other problems. The script ran afoul of, first, Hollywood’s watchdog of so-called “moral correctness,” the dreaded Hays Office, which found some themes “unacceptable.” Second, the Catholic Legion of Decency (CLD), much more influential then than now, insisted that the horrors of the Inquisition be considerably moderated. What horrors remain give a true sense of this terror organization—the amply furnished torture chamber for heretics and the church “friend” of the family who piously betrays them, darkly played by one of those great arch villains of moviedom, George Zucco as Marquis de Caravajal.

Perhaps the film’s greatest strength, swashbuckler or not, is the score by Alfred Newman, the only Oscar nomination the film received. A win was denied by Miklós Rózsa’s darker, perhaps more original score for A Double Life, about a Shakespearean actor gone berserk.

Captain from Castile begins in Spain, the early years of the sixteenth century. A member of the aristocracy, Pedro de Vargas (Power), after assisting a runaway Aztec slave, Coatl (Jay Silverheels), comes up against Diego de Silva (John Sutton), a zealous nobleman ever watchful for heretics for the Spanish Inquisition. After helping Coatl, Pedro encounters a barmaid, Cataña Pérez (Peters), and a soldier of fortune, Juan Garcia (Lee J. Cobb, in his usual blustery manner), fleeing the Inquisition.

Captain from Castile begins in Spain, the early years of the sixteenth century. A member of the aristocracy, Pedro de Vargas (Power), after assisting a runaway Aztec slave, Coatl (Jay Silverheels), comes up against Diego de Silva (John Sutton), a zealous nobleman ever watchful for heretics for the Spanish Inquisition. After helping Coatl, Pedro encounters a barmaid, Cataña Pérez (Peters), and a soldier of fortune, Juan Garcia (Lee J. Cobb, in his usual blustery manner), fleeing the Inquisition.

Pedro’s father (Antonio Moreno) fails to accept de Silva’s warped view of Christianity, and de Silva has another reason to dislike the family—he is competing for the affections of Pedro’s young lady, Luisa (a strangely miscast Barbara Lawrence, complete with a 1940s hair style).

De Silva eventually imprisons the de Vargas family on charges of heresy, resulting in the death of Pedro’s sister during a botched torture. In a brief duel in his cell, Pedro runs de Silva through, presumably killing him. The entire de Vargas family escapes, Pedro, Cataña and Juan diverting the pursuing soldiers away from his parents.

Hernán Cortéz (Cesar Romero, in perhaps his signature role; if not this, then as The Joker in the 1960s TV series, Batman) is preparing a voyage to the New World, and Pedro joins him, along with Cataña and Juan, even Coatl.

Hernán Cortéz (Cesar Romero, in perhaps his signature role; if not this, then as The Joker in the 1960s TV series, Batman) is preparing a voyage to the New World, and Pedro joins him, along with Cataña and Juan, even Coatl.

In Mexico, Pedro confesses to Father Bartolomé (Thomas Gomez) his killing of de Silva and is granted a penance, to pray for de Silva’s soul. Despite the class differences, Pedro and Cataña fall in love. There are some unexpected problems, for one a certain pregnancy, one of the sticking points for the CLD. And, too, the arrival of a surprise visitor—de Silva is alive after all!—puts Pedro under a sentence of death when the guy turns up murdered. Rather than allow Pedro to die for a crime he did not commit, Coatl confesses that he had killed de Silva.

The conquistadors find a bit of Aztec gold, and in the film’s final scene, Cortez and his men, not satisfied with their take, though greed is a passive theme here, march off for further conquests and more gold, to kill, Christianize the lost-souled “savages” and spread disease. Even Pedro and Cataña, staring blithely ahead over the lush landscape the Spaniards will soon seize, take this all in stride.

These glorified marauders tramp, by the way, to the “Conquest” March, the most famous part—and rightly so—of Alfred Newman’s magnificent music. It remains to this day one of the best in the film score repertoire. So captivated was the public after the premiere that the music was among the first scores ever released on records, three double-sided 78s, or about twenty minutes. As film historian and record producer Tony Thomas wrote in his notes for an LP reissue of the original music in 1975, “[The discs were] considered so hi-fi in their day that record dealers often used the ‘Conquest’ side as a demonstration record.”

Also gleaned from Mr. Thomas’ notes, a quote from Newman’s orchestrator, Edward Powell, gives a glimpse at the composer, man and artist: “I’ve often thought that Alfred chose to do this score because of the opportunities it gave him as a conductor. Conducting was his real love and we scored Castile for seventy-four pieces. It was a picture that allowed him full range as a composer. . . . The key phrase of the score, the twelve-bar ‘Conquistador’ theme, came to him early in the job . . . ”

Also gleaned from Mr. Thomas’ notes, a quote from Newman’s orchestrator, Edward Powell, gives a glimpse at the composer, man and artist: “I’ve often thought that Alfred chose to do this score because of the opportunities it gave him as a conductor. Conducting was his real love and we scored Castile for seventy-four pieces. It was a picture that allowed him full range as a composer. . . . The key phrase of the score, the twelve-bar ‘Conquistador’ theme, came to him early in the job . . . ”

Aside from the famous march, which runs throughout the film in one guise or another, the score has countless high points. The lilting music representing Cataña, first heard on the oboe d’amore, is in a class with “Conquest,” though diametrically of different color and tone, and purpose. On one occasion, Cataña’s music and a subtle allusion to the march are skillfully interwoven in a fabric of almost impressionistic hues.

Newman was famous for his swooning, romantic tunes and the lushness he could obtain from the strings came to represent the epitome of “the Hollywood sound,” a sound Bernard Herrmann, for one, famously did not want. The evocative string harmonies in an ocean scene in Cuba recall a similar string sound in the opening movement, “Palérmo,” of Jacques Ibert’s Escales (Ports of Call).

Newman is easily capable, however, of creating contrastingly dark musical images in other sequences, including underpinnings for the Spanish Inquisition, the destruction of Cortez’ armada (so his men couldn’t commandeer it for Spain) and Pedro’s duel with de Silva.

Newman is easily capable, however, of creating contrastingly dark musical images in other sequences, including underpinnings for the Spanish Inquisition, the destruction of Cortez’ armada (so his men couldn’t commandeer it for Spain) and Pedro’s duel with de Silva.

Although modern recordings of the Captain from Castile score have appeared since 1947, the original soundtrack reissue from Screen Archives Entertainment—over ninety minutes of music—can be recommended, despite its age. The uncovering of long-stored Hollywood archives have shown that the studios were experimenting with multiple angle, or dual channel, sound as early as M-G-M’s Meet the Baron in 1933.

Except for the main title, which is heard “flat,” this Captain from Castile soundtrack recording has, certainly, a respectable semblance of stereo. Hiss from the original audio tapes is so minimal as to be unnoticed, and although there are a few instances of optical track damage too acute to be remedied by computer, these flaws last for only a few seconds. The over-all sound is amazing indeed, and should not offend anyone’s hearing.

Vicente Gomez (1911-2001), guitarist and composer for a number of films, including The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Sun Also Rises, sprinkles his playing throughout the film, his instrument adding an authentic Spanish flavor to things. Sometimes he composed his own pieces, most passionate the “Granada Arabe” for Pedro and Cataña’s zarabanda, a reputedly indecent Spanish dance of seduction.

The two-disc set is lavishly packaged, the design of Charles Johnston, with a 42-page color booklet, brightly illustrated and filled with production and film stills. Movie historian Rudy Behlmer expertly writes about the film itself, Jon Burlingame reviews the background on Newman’s score and Ray Faiola provides a detailed synopsis of the plot. The booklet is a treat in itself.