“Allow me to thank you. You have helped me after all. I always knew the power you have over Mrs. Cunningham. But now I know why. I know what she means to you.” — Herbert Lom to James Mason

One psychiatrist in the beginning of The Seventh Veil is talking to another, saying that exploring mental illness is sometimes analogous to Richard Strauss’ “Dance of the Seven Veils” from Salome, a once scandalous opera that premiered in 1905. The secrets of an unstable mind, this doctor said, are revealed gradually, like opaque veils being removed, one by one, from a patient’s subconscious, and, with the seventh and last veil, all is revealed. I’ve just seen the film for the first time—and it was made in 1945!

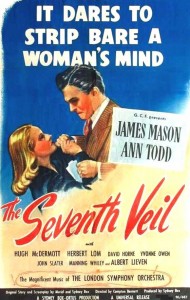

That lack of curiosity puzzles me. I had read enough about the film to know it starred James Mason—and that the plot centered around a classical pianist. James Mason remains one of my favorite actors, and I’m still a classical music fanatic. Some critics have said it is his best role. Perhaps. The first shot of Ann Todd, a close-up of her head resting on a pillow, with a kind of luminous light, reminded me of Greta Garbo—the long, straight hair, a prominent, curled nose and—dare I say it?—something of that icon’s beauty.

That lack of curiosity puzzles me. I had read enough about the film to know it starred James Mason—and that the plot centered around a classical pianist. James Mason remains one of my favorite actors, and I’m still a classical music fanatic. Some critics have said it is his best role. Perhaps. The first shot of Ann Todd, a close-up of her head resting on a pillow, with a kind of luminous light, reminded me of Greta Garbo—the long, straight hair, a prominent, curled nose and—dare I say it?—something of that icon’s beauty.

The movie began, I thought, extraordinarily—Ann Todd running from her hospital bed, out into the hall and down the street, and jumping off a bridge, a vivid use of film noir light and shadow and unsettling music by Benjamin Frankel, who would do better things later in The Night of the Iguana, The Importance of Being Ernest (1952) and Battle of the Bulge. “Better things” because the remainder of the score, what there is of it, is uninteresting, much like the photography by Reginald H. Wyer, whose best film this probably was. The film noir touches become less and less an ingredient as well.

What is exceptional—on a Hollywood scale and opulence (not necessarily always a plus, of course)—is the single set of Nicholas’ (James Mason) mansion, a salon whose vastness and exaggerated height is distantly photographed to emphasize the diminutive entry of the teenage Francesca Cunningham (a not “quite” convincing 36-year-old Ann Todd!), when she meets her second cousin and new guardian. Nicholas’ voice is first heard through the back of an enormous lounge chair—to match the room—whose flaring, scrolled sides seem almost comical, as if a hiding place for the Mad Hatter. Which reminds me that James Mason had earlier starred, along with Deborah Kerr and Robert Newton, in the film version of A. J. Cronin’s novel, Hatter’s Castle. No connection with Veil’s original story and screenplay by Muriel and Sydney Box, who won Oscars for their writing.

What is exceptional—on a Hollywood scale and opulence (not necessarily always a plus, of course)—is the single set of Nicholas’ (James Mason) mansion, a salon whose vastness and exaggerated height is distantly photographed to emphasize the diminutive entry of the teenage Francesca Cunningham (a not “quite” convincing 36-year-old Ann Todd!), when she meets her second cousin and new guardian. Nicholas’ voice is first heard through the back of an enormous lounge chair—to match the room—whose flaring, scrolled sides seem almost comical, as if a hiding place for the Mad Hatter. Which reminds me that James Mason had earlier starred, along with Deborah Kerr and Robert Newton, in the film version of A. J. Cronin’s novel, Hatter’s Castle. No connection with Veil’s original story and screenplay by Muriel and Sydney Box, who won Oscars for their writing.

The film is almost claustrophobic in its confining interiors. Even the concert hall where Francesca plays the Grieg Piano Concerto is photographed in tight and medium shots, with only a few members of the orchestra seen behind her and little audience shown: obviously a small set, not an actual auditorium. An exterior shot of the Royal Albert Hall from the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park is a welcomed escape. The poster for the program indicates Muir Mathieson as her conductor, the man who conducted perhaps more film scores, on screen and in albums, than any other.

The movie begins, as indicated, with Francesca in the hospital—mental hospital it’s soon revealed. Recovering from her unsuccessful suicide attempt, she tells her life’s story to psychiatrist Dr. Larsen (Herbert Lom). (This is one of those rare films where the psychiatrist doesn’t fall in love with his patient.) She relates going to live with her crippled, pianist guardian, Nicholas, who imperiously turns her piano talents into concert pianist proportions. And she dutifully becomes famous, as a love of music drives her as much as it drives her cousin.

The movie begins, as indicated, with Francesca in the hospital—mental hospital it’s soon revealed. Recovering from her unsuccessful suicide attempt, she tells her life’s story to psychiatrist Dr. Larsen (Herbert Lom). (This is one of those rare films where the psychiatrist doesn’t fall in love with his patient.) She relates going to live with her crippled, pianist guardian, Nicholas, who imperiously turns her piano talents into concert pianist proportions. And she dutifully becomes famous, as a love of music drives her as much as it drives her cousin.

Francesca’s first love is an “American” band leader (British actor Hugh McDermott, sans an American accent), but when she informs Nicholas she plans to marry, he decrees otherwise, as he is her guardian until she’s twenty-one. Her next love—they agree to live together—is a painter, Max (German actor Albert Lieven). Nicholas commissions him to paint her portrait, which eventually hangs on Nicholas’ wall, á la Gene Tierney’s portrait in Laura, Joanne Woodward’s in Sleuth, Jennifer Jones’ in Portrait of Jennie.

Francesca’s first love is an “American” band leader (British actor Hugh McDermott, sans an American accent), but when she informs Nicholas she plans to marry, he decrees otherwise, as he is her guardian until she’s twenty-one. Her next love—they agree to live together—is a painter, Max (German actor Albert Lieven). Nicholas commissions him to paint her portrait, which eventually hangs on Nicholas’ wall, á la Gene Tierney’s portrait in Laura, Joanne Woodward’s in Sleuth, Jennifer Jones’ in Portrait of Jennie.

Nicholas is again enraged to hear he might lose his control over Francesca. While she’s playing Beethoven’s “Pathétique” Sonata, he strikes her hands with his cane. Funny how you can tell he was going to strike her—the way he entered the room, how he held his cane and given his rage. In fleeing the mansion, she and Max have an automobile accident.

Francesca recounting her past life is over and the story segues into the present.

As if the blow with the cane wasn’t enough, her hands are now severely burned from the accident. She is convinced she will never play again, but Dr. Larsen believes hearing music that has a special meaning will stimulate her to play. In search of such healing music, he plays for Nicholas a recording of the second movement of the “Pathétique” Sonata (an HMV 78 r.p.m., of course). Nicholas, in another rage, smashes the shellac disc. Having possibly found the right music, Larsen somehow finds another disc of the same piece (also an HMV) for Francesca to hear. Dr. Larsen places her hands on the keyboard and she begins to play.

In a confrontation with Nicholas and Max—his arm bandaged from the accident—Francesca realizes Nicholas is the man she really loves—no matter the age difference, remembering, now, that he was already a grown man when she met him as a teenager. Shhh-h-h-h—— (Mason and Todd were actually the same age.)

Although there is solo piano music by Mozart, Chopin and Beethoven, as well as the Grieg concerto and Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 2, there is no real technical discussions of music, so Francesca’s and Nicholas’ love of music isn’t fleshed out, made convincing. When she is filmed from the back or across the piano, Todd does an excellent job of mimicking a pianist’s arm movements and expertly simulates keyboard fingering in one instance, although otherwise all close-ups of hands are those of Eileen Joyce. Joyce also played the same Rachmaninoff concerto in Brief Encounter, released in Great Britain about the time of Veil.

Although there is solo piano music by Mozart, Chopin and Beethoven, as well as the Grieg concerto and Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 2, there is no real technical discussions of music, so Francesca’s and Nicholas’ love of music isn’t fleshed out, made convincing. When she is filmed from the back or across the piano, Todd does an excellent job of mimicking a pianist’s arm movements and expertly simulates keyboard fingering in one instance, although otherwise all close-ups of hands are those of Eileen Joyce. Joyce also played the same Rachmaninoff concerto in Brief Encounter, released in Great Britain about the time of Veil.