“A man born . . . on the wrong side of the blanket can, nonetheless, inherit the features of his father—his pride, his patience and his vengeful spirit.”— Hercule Poirot (David Suchet)

So what’s a good Christmas gift to instill in you the spirit of the season? Something traditional: “A partridge in a pear tree”? Or something practical: “Copper kettles and warm woolen mittens”? Or, maybe, something regained, to have back under the tree: the “snoof, the fuzzles and tringlers” stolen from Whoville by that old Grinch? No, no—these gifts are hardly appropriate, particularly from one special person. And would you mind the gift a day or two early—and, unfortunately, unwrapped? But, then, there’s no choice when the gift is . . . MURDER.

And a most peculiar murder, besides, of course, the body being too large to fit under the tree. From upstairs in an old millionaire’s mansion, there’s a hair-raising scream, more like, one might say, a squeal, and this mixed with a terrible crashing, which ceases as abruptly as it had begun. The three sons of the old man use a heavy bench as a battering ram to breach the thick oaken door. Five lunges. Finally, the door splinters.

Spread out on the floor, among an array of upturned furniture and surrounded by an enormous amount of blood, is the wheelchair-bound patriarch of the family, Simeon Lee. Dead, most assuredly. His throat cut. The diamonds in his safe gone. Yes, the single door to the second-floor room had been locked from the inside and the only conceivable way out is a row of closed windows, one locked ajar for ventilation. Superintendent of Police Sugden had fortunately just returned to the house, now to retrieve a left-behind book, after an earlier visit to collect money for the police orphanage.

Spread out on the floor, among an array of upturned furniture and surrounded by an enormous amount of blood, is the wheelchair-bound patriarch of the family, Simeon Lee. Dead, most assuredly. His throat cut. The diamonds in his safe gone. Yes, the single door to the second-floor room had been locked from the inside and the only conceivable way out is a row of closed windows, one locked ajar for ventilation. Superintendent of Police Sugden had fortunately just returned to the house, now to retrieve a left-behind book, after an earlier visit to collect money for the police orphanage.

Another recent arrival at the house, invited like the rest of the family for Christmas by the cruel Simeon, is a dark-haired woman. Pilar had bent down to pick up something from the floor, and Sugden, after having warned everyone that nothing must be disturbed, asked her for it. She handed him a little rubber ring and a small wooden object, which he tucked into his breast pocket.

An Agatha Christie mystery? Of course.

Hercule Poirot had been among those who entered the old man’s murder room, invited by Simeon in a phone call to stay at Gorston Hall for Christmas, and to “keep his eyes and ears open.” When Poirot asked if he’d received any threats, Simeon replied, “Ah, well, you’d have to be here to understand.” It’s possible Poirot might’ve refused, but his radiator having just gone cold and Simeon having asserted that, yes, his house had “the central heating,” Poirot declared he would arrive the next day.

Hercule Poirot had been among those who entered the old man’s murder room, invited by Simeon in a phone call to stay at Gorston Hall for Christmas, and to “keep his eyes and ears open.” When Poirot asked if he’d received any threats, Simeon replied, “Ah, well, you’d have to be here to understand.” It’s possible Poirot might’ve refused, but his radiator having just gone cold and Simeon having asserted that, yes, his house had “the central heating,” Poirot declared he would arrive the next day.

At this point, David Suchet was almost half way through the seventy installments of the Poirot segment of British/PBS’s Masterpiece Mystery series, which had begun in 1989 with The Adventure of the Clapham Cook, from a Christie short story collection, and which would end in 2013 with Curtain, the detective’s last case—and death.

Mistress of the whodunit genre, Christie had received criticism from her brother-in-law, James, that her murders were becoming “too refined, anemic,” that he yearned for “a good violent murder with lots of blood.” Agatha responded in 1938 with Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, also known as Murder for Christmas and A Holiday for Murder. She even prefaced this latest exercise in crime with a brief reply to James and, further, quoted from Macbeth, Act V, scene 1: “Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?”—a line spoken in both novel and movie.

Mistress of the whodunit genre, Christie had received criticism from her brother-in-law, James, that her murders were becoming “too refined, anemic,” that he yearned for “a good violent murder with lots of blood.” Agatha responded in 1938 with Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, also known as Murder for Christmas and A Holiday for Murder. She even prefaced this latest exercise in crime with a brief reply to James and, further, quoted from Macbeth, Act V, scene 1: “Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?”—a line spoken in both novel and movie.

This particular mystery is, admittedly, not among Christie’s best and is never listed by scholars and critics in that category. The best novels cited always include The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Peril at End House, Thirteen for Dinner and The A.B.C. Murders, all of which, incidentally, are Poirot mysteries, versus, say, the weaker Miss Marple and Ariadne Oliver whodunits.

Not to worry, not to be discouraged from seeing this TV movie version, for the transfer to the screen has evolved with decided improvements. In any number of ways, the PBS TV version emerges more interesting and more nuanced than the original mystery itself—and more Christmassy. This is primarily thanks to a first-class team of Brits who often collaborated on the Poirot series—Edward Bennett the director, Brian Eastman the producer (of forty-nine of the Poirot episodes) and Clive Exton the creative screenwriter.

Christopher Gunning’s musical contribution, however, is a mixed bag. The Christmas carols that begin each new day—the calendar date shown on screen—add seasonal flavor, as do the allusions to these songs within the score, beneath dialogue or as transitions between scenes. The sinister scoring of dark, low-register instruments to accompany Simeon’s always suspicious activities is original and a dynamic contrast with the bright carols. One especially negative point: after Poirot has played his radio—a suggestion of the Baroque—before he leaves his apartment for Gorston Hall, this music persists annoyingly, and inexplicably, barely audible, through subsequent scenes in the score.

Christopher Gunning’s musical contribution, however, is a mixed bag. The Christmas carols that begin each new day—the calendar date shown on screen—add seasonal flavor, as do the allusions to these songs within the score, beneath dialogue or as transitions between scenes. The sinister scoring of dark, low-register instruments to accompany Simeon’s always suspicious activities is original and a dynamic contrast with the bright carols. One especially negative point: after Poirot has played his radio—a suggestion of the Baroque—before he leaves his apartment for Gorston Hall, this music persists annoyingly, and inexplicably, barely audible, through subsequent scenes in the score.

As everyone knows who has read Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, Poirot does not arrive until Christmas Eve, the day after the murder, or a little more than a quarter into the book. So in certain scenes in the film, he is merely a silent onlooker, since, after all, he wasn’t there in the novel. For example, when Simeon makes an especially provocative announcement to his family, Poirot never speaks and is never seen among the group, only in isolated inserts, almost as an afterthought, which, indeed, he is.

Each of Christie’s seven chapters is headed with a date, December 22nd through the 28th, which doesn’t always correspond with the chronology on screen. Shortcuts were taken in eliminating at least three characters—a fourth Lee son, David; Stephen Farr, a stranger from South Africa; and a Poirot friend, Colonel Johnson, Chief Constable of Middleshire, who alerts him to the murder and takes him to Gorston Hall.

What will prove to be a fine holiday movie, with carols, seasonal décor, a picturesque English village and plenty of snow, opens, however, far afield—in South Africa, 1896, an introduction not in the novel. Two men dig for diamonds together, a young Simeon Lee (Scott Handy) and partner Gerrit (Oscar Pearce). Greed overcomes them and they fight. Lee kills Gerrit, takes the pouch of uncut diamonds and leaves on horseback. The heat and a wound received from Gerrit overcome him. He is rescued by Stella (Liese Benjamin) and taken to her shack where he recovers. The two become lovers. One morning Stella awakens to find Lee, and the diamonds, gone.

What will prove to be a fine holiday movie, with carols, seasonal décor, a picturesque English village and plenty of snow, opens, however, far afield—in South Africa, 1896, an introduction not in the novel. Two men dig for diamonds together, a young Simeon Lee (Scott Handy) and partner Gerrit (Oscar Pearce). Greed overcomes them and they fight. Lee kills Gerrit, takes the pouch of uncut diamonds and leaves on horseback. The heat and a wound received from Gerrit overcome him. He is rescued by Stella (Liese Benjamin) and taken to her shack where he recovers. The two become lovers. One morning Stella awakens to find Lee, and the diamonds, gone.

London, forty years later, 1936, and a small Salvation Army choir is singing “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear.” As Hercule Poirot and his confidant in any number of cases, Inspector Japp (Philip Jackson), are leaving a pub, Japp says he’s going to spend Christmas with his wife’s family in Wales and dreads their endless carol-singing. “For Poirot,” the mustachioed detective responds, “it will be a quiet Christmas with my radio perhaps, a book and a box of exquisite Belgian chocolates.”

“Think of me on Christmas morning,” the inspector says, “when you open this.” He offers a small package.

No radio for long, no box of chocolates, as there’s no heat, and so Poirot accepts Simeon Lee’s (Vernon Dobtcheff) timely offer—urgent request, more accurately—to spend Christmas at warm Gorston Hall.

No radio for long, no box of chocolates, as there’s no heat, and so Poirot accepts Simeon Lee’s (Vernon Dobtcheff) timely offer—urgent request, more accurately—to spend Christmas at warm Gorston Hall.

Everything from the African introduction to his point comes from the imagination of screenwriter Exton. More subtle changes and a few additions will follow.

Thus Poirot arrives at Gorston Hall, and by now it is December 22nd, introduced by a boys’ choir singing “I Saw Three Ships.” In a first meeting with Poirot, Simeon says, “All my sons are complete nincompoops. I’ve probably got better sons scattered round the world, born on the wrong side of the blanket. My family hates me. Well, I’m going to make an announcement this evening and then they’ll have good cause to hate me.”

Poirot is dismissed and Pilar Estravados (Sasha Behar) enters the bedroom. Simeon shows her the first diamonds, still uncut, he had taken from his first diamond mine. Diamonds had made his fortune. “It’s a long time,” he says, leering at her, “since I was close to anything as young and beautiful as you are. It warms my old bones.” And he boastfully confesses, “I’ve been a very wicked man, Pilar. I’ve enjoyed every moment of it. I’ve cheated and I’ve stolen and I’ve lied—and the woman!”

Poirot is dismissed and Pilar Estravados (Sasha Behar) enters the bedroom. Simeon shows her the first diamonds, still uncut, he had taken from his first diamond mine. Diamonds had made his fortune. “It’s a long time,” he says, leering at her, “since I was close to anything as young and beautiful as you are. It warms my old bones.” And he boastfully confesses, “I’ve been a very wicked man, Pilar. I’ve enjoyed every moment of it. I’ve cheated and I’ve stolen and I’ve lied—and the woman!”

Shortly after this, Simeon greets the family in his bedroom, intentionally allowing everyone to hear him on the phone; he tells his lawyer the situation has changed, that he plans to alter his will. (Come on, Agatha, this is the oldest plot device in the mystery genre!) “I shan’t be dying just yet!” Simeon cackles and hangs up.

Soon after, while the family is sitting around following a tense, silent dinner, Superintendent Sugden (Mark Tandy) drops by to collect for the orphanage, visits Simeon, then leaves. Poirot warms himself by the fire, strangely intimidated by the heavy atmosphere in the room and ignored by a family baffled by this peculiar guest of Simeon’s.

And then comes that scream and the horrendous crash from upstairs, the breaking down of the door, the body on the floor and the timely return of Superintendent Sugden.

And then comes that scream and the horrendous crash from upstairs, the breaking down of the door, the body on the floor and the timely return of Superintendent Sugden.

It is now December 23rd. Sure enough, Inspector Japp is suffering. His relatives are singing “Ding Dong Merrily on High” when, at the door, appears Poirot. “I’ve come to rescue you,” he says. “Superintendent Sugden was going to call in Scotland Yard in any case, so I suggested that, as you were just across the border——”

Poirot has, by now, appraised the suspects, an unpleasant lot in general:

First is George (Eric Carte), one of Simeon Lee’s three sons. He comes to Gorston Hall to suffer, along with everyone else, the torrent of invectives from the old man. An MP, George nevertheless takes an allowance from his father, for himself and his wife, Magdalene (Andrée Bernard), who complains, “When [Simeon] gets me alone, he makes me feel quite uncomfortable.”

The eldest son, Alfred (Simon Roberts), has been living at Gorston Hall and devoting all his time to his invalid father’s welfare. His wife, Lydia (Catherine Rabett), hates Simeon, as she realizes how much her husband’s devotion has restricted their lives. Her miniature gardens, Italian, Japanese and a desert oasis, seem to fascinate everyone. Japp is unimpressed: “What’s the point of a miniature garden? You can’t do anything with it. You can’t take a deck chair out and sit in it.”

The eldest son, Alfred (Simon Roberts), has been living at Gorston Hall and devoting all his time to his invalid father’s welfare. His wife, Lydia (Catherine Rabett), hates Simeon, as she realizes how much her husband’s devotion has restricted their lives. Her miniature gardens, Italian, Japanese and a desert oasis, seem to fascinate everyone. Japp is unimpressed: “What’s the point of a miniature garden? You can’t do anything with it. You can’t take a deck chair out and sit in it.”

Then there’s the black sheep of the family, Harry Lee (Brian Gwaspari), who has returned from abroad upon his father’s invitation. A bachelor and womanizer who eyes the ladies as he passes through the train, he invites himself to share a table with an attractive, dark-haired woman who identifies herself as Pilar Estravados, half-Spanish, Simeon’s only granddaughter, also on her way to Gorston Hall for Christmas.

Among the staff at Gorston, there’s the suspicious behavior of the chauffeur, Horbury (Ayub Khan-Din), who breaks a coffee cup when he hears that Sugden is investigating his master’s death. Earlier, Horbury had picked up Poirot, Harry and Pilar at the train station. Harry is another person who assumes the detective is French, which, unusually, this time goes uncorrected by Poirot, who, of course, is Belgian. With the two in mind, Harry says, “You two should get on, being foreign.”

Among the staff at Gorston, there’s the suspicious behavior of the chauffeur, Horbury (Ayub Khan-Din), who breaks a coffee cup when he hears that Sugden is investigating his master’s death. Earlier, Horbury had picked up Poirot, Harry and Pilar at the train station. Harry is another person who assumes the detective is French, which, unusually, this time goes uncorrected by Poirot, who, of course, is Belgian. With the two in mind, Harry says, “You two should get on, being foreign.”

Overall, or taken individually for that matter, the Lee family are a jealous, scheming, unattractive lot. Simeon especially. (If Dobtcheff is guilty of more than a little overacting, his Simeon is nonetheless convincing as a depository of sin and evil.) While Harry is obviously made from his father’s mold, he may be the most interesting of the group, with glimmers of decency beneath the family trait of avarice. Lydia, even, approaches kindness, willing to share her part from the will with Pilar, who has been excluded.

The one area where Hercule Poirot’s Christmas can be ranked among Agatha Christie’s best mysteries is the abundant clues. If not particularly proficient in character-building—her individuals all seem to run together—Christie is a master of clues:

The one area where Hercule Poirot’s Christmas can be ranked among Agatha Christie’s best mysteries is the abundant clues. If not particularly proficient in character-building—her individuals all seem to run together—Christie is a master of clues:

- First, there is the observation by the butler, Tressilian (John Horsley), who greets visitors at the door: “It seems sometimes as if the past isn’t the past at all. It seems to be, the bell rings and I go to let someone in. Doesn’t matter if it’s Mr. Harry or Mr. George or Superintendent Sugden, even. But I’m saying to myself, ‘But I’ve done all this before.’ ”

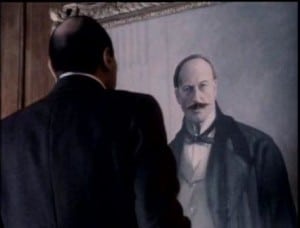

Inspired by this, Poirot purchases a regimental mustache kit at the local general store and affixes the whiskers to the portrait of a middle-aged Simeon Lee in the sitting room. (The camera frequently shows the portrait, as if nudging, urging the viewer to observe, observe, observe.) “All of the men in the Lee family,” Poirot says, “have a likeness that is most strong.” And remembering Simeon’s comment that he had sired a number of illegitimate children, the detective announces that, just possibly, the murderer “ . . . might be a member of the family and, at the same time, a stranger.”

Inspired by this, Poirot purchases a regimental mustache kit at the local general store and affixes the whiskers to the portrait of a middle-aged Simeon Lee in the sitting room. (The camera frequently shows the portrait, as if nudging, urging the viewer to observe, observe, observe.) “All of the men in the Lee family,” Poirot says, “have a likeness that is most strong.” And remembering Simeon’s comment that he had sired a number of illegitimate children, the detective announces that, just possibly, the murderer “ . . . might be a member of the family and, at the same time, a stranger.”- Harry Lee somehow noticed—a keen observer of things, he admits—that the key in the door of Simeon’s bedroom was on the inside.

- Horbury’s suspicious dropping of the coffee cup and the later revelation of his criminal background.

- The empty diamond case is found in Magdalene’s room.

- The missing uncut diamonds are found in Lydia’s little Japanese garden.

- George has a weak alibi regarding the length of some phone calls and his father had planned to cut his allowance.

- During the December 24th celebrations, Pilar, observed by all, accidentally bursts a balloon beside the Christmas tree and recognizes that the little rubber ring is like the one she found by Simeon’s body. Yes, the little rubber ring and the piece of wood——

- Later unsuccessfully attacked in a hallway, Pilar is found to be an impostor, real name Conchita Lopez, having assumed the new identity when the real Pilar Estravados was killed in a car accident in Spain.

- And, oh, yes, a mysterious lady in veiled black (Olga Lowe) checks into the local Bull Inn and is seen playing solitaire and sitting in the background, unnoticed, when Japp, Poirot and Harry stop in for drinks.

While the novel’s final lines return to Poirot’s preference for “the central heating” over Colonel Johnson’s enjoyment of a wood fire, the movie ends more imaginatively—and with a touch of the old English Yuletide spirit, Poirot style.

It’s now December 25th and a choir has serenaded the still dysfunctional Lee family with “From the Realms of Glory.” As Poirot and Japp are being driven away from Gorston Hall in a taxi, Poirot presents his companion with a box of Jamaican cigars and shows his own present from the inspector. The pair of garishly colored knitted mittens he had opened earlier, with some dismay. But now he feigns elation: “Such wonderful colors. Such workmanship.” Japp wonders why he doesn’t wear them now. “No, no, mon ami,” Poirot replies. “These must be kept for best. I shall wear them only when I go to church.”

It’s now December 25th and a choir has serenaded the still dysfunctional Lee family with “From the Realms of Glory.” As Poirot and Japp are being driven away from Gorston Hall in a taxi, Poirot presents his companion with a box of Jamaican cigars and shows his own present from the inspector. The pair of garishly colored knitted mittens he had opened earlier, with some dismay. But now he feigns elation: “Such wonderful colors. Such workmanship.” Japp wonders why he doesn’t wear them now. “No, no, mon ami,” Poirot replies. “These must be kept for best. I shall wear them only when I go to church.”

For those who know Poirot from reading just a few of the mysteries, although he is a reasonably devout Catholic, references to his “going to church” from Christie are rare.

In the mystery’s solution, during Hercule Poirot’s expected and required dénouement, he suggests that each and everyone of the assembled suspects has a reason for doing in Simeon Lee, and he provides possible evidence. He explains how the murder was committed—why the disarrayed furniture, why the little circle of rubber and piece of wood, why the ajar window, why a locked door with the key on the inside. (Dame Agatha here creates one of her most convoluted murder schemes—and one bordering on the impracticable.)

After all this, a puzzled Japp asks just who is the murderer. “In order to answer your question,” Poirot replies, “it is necessary that we make a short journey. Suivez moi.” A journey, as it turns out, to the Bull Inn in the nearby village and a knock on the door of room number ten.

After all this, a puzzled Japp asks just who is the murderer. “In order to answer your question,” Poirot replies, “it is necessary that we make a short journey. Suivez moi.” A journey, as it turns out, to the Bull Inn in the nearby village and a knock on the door of room number ten.

Think you’ve figured out the murderer—and explained the murder scene? Well, to make sure, watch Hercule Poirot’s Christmas—with a bowl of fresh popcorn, the tree lit and, hopefully, with no unsightly, unwrapped . . . well, you know . . . under the tree.