“When we get back to the ranch, I want you to change the brand. . . . And we’ll add an ‘M’ to it. You don’t mind that, do you?” —— Thomas Dunson to Matthew Garth

Borden Chase, screenwriter best known for Westerns—Bend of the River, The Far Country, Winchester ’73, Man Without a Star—was also an uncredited writer on the Mutiny on the Bounty remake in 1962. Quite appropriately, he dubbed Red River, which he also co-scripted, a Western version of that nautical story. Only now, the ruthless captain on a voyage across vast oceans is replaced by an equally ruthless trail boss on a cattle drive across the open plains of an 1860s America. And on that cattle drive, the leader of the revolt is not the friend and first mate on that voyage, but an adopted son of sorts, also second-in-command.

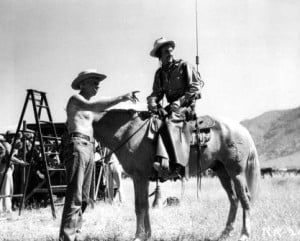

The hard-nosed trail boss, Thomas Dunson, is played by John Wayne, in one of his few unsympathetic roles—and played superbly, not to be equaled until the negative portrayal of Ethan Edwards in The Searchers eight years later, in 1956. After viewing Red River, John Ford, who directed the later Western, said in typical blunt, Fordian language, “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act.”

And for the role of the insurgent who mutinies against the ruthless Dunson, Montgomery Clift doesn’t bare his acting teeth and thespian expressions, but being a method actor, his performance is internal. This acting style could have easily clashed with Wayne’s external approach, which is more about personal charisma, Wayne being Wayne. Such disparate juxtapositions have been known to ruin pictures; here, in fact, the contrast is exciting and the two styles complement one another.

Red River would have been Clift’s first screen appearance had not the movie been put on the shelf for two years, mainly for a supposed legal scrap over Howard Hughes’ claim that the movie had borrowed heavily from The Outlaw, which Hughes had directed in 1943. In the meantime, Clift made The Search; it was released six months before Red River, also in 1948.

Red River would have been Clift’s first screen appearance had not the movie been put on the shelf for two years, mainly for a supposed legal scrap over Howard Hughes’ claim that the movie had borrowed heavily from The Outlaw, which Hughes had directed in 1943. In the meantime, Clift made The Search; it was released six months before Red River, also in 1948.

Other impressive artists contributed to the success of Red River, making it one of the great entries in the Western genre. This profusion of concentrated talent was typical of the period, even in this, the twilight years of Hollywood’s “golden age”—so-called because time has proven it to be just that. The director of Red River, Howard Hawks, not unlike Ford in his no-nonsense approach to his art, was, in 1948, already well established as one of the great American directors. Hawks had, in fact, an uncredited hand in directing The Outlaw, which, seventy years after Jane Russell’s then salacious “exposure,” seems less deserving of its earlier attention.

Hawk’s conspicuous lack of an Oscar—he was nominated only once and that for Sergeant York in 1941—remains amazing, and somewhat scandalous, in view of his diverse and Oscar-worthy efforts: Bringing Up Baby, His Girl Friday, To Have and Have Not and Rio Bravo. Friend Ford, after he had won Best Picture for How Green Was My Valley, told Hawks he should have won for Sergeant York. To go a step further, in this writer’s opinion, the also nominated Citizen Kane should have won. Reflective of the Academy’s usual feet-dragging wisdom, in the last years of Hawks’ life he did receive what could only be called a “consolation” honorary Oscar for “A master American filmmaker whose creative efforts hold a distinguished place in world cinema.”

For his cinematographer, Hawks had originally wanted Gregg Toland, who was otherwise committed. He fortunately settled on Russell Harlan, no slouch himself, who would often work for Hawks (The Big Sky, Rio Bravo, Hatari!) and for directors Billy Wilder (Witness for the Prosecution), Robert Mulligan (To Kill A Mockingbird) and others. Harlan’s all-embracing camera captures the scope and grandeur of the western vistas and Dunson’s enormous herd of cattle on the move, whether stampeding or crossing rivers; that same camera, sensitive and more intimate in the night photography, emphasizes the chiaroscuro of simple campfires or lantern light, demonstrating another instance of the superiority of black-and-white over color.

For his cinematographer, Hawks had originally wanted Gregg Toland, who was otherwise committed. He fortunately settled on Russell Harlan, no slouch himself, who would often work for Hawks (The Big Sky, Rio Bravo, Hatari!) and for directors Billy Wilder (Witness for the Prosecution), Robert Mulligan (To Kill A Mockingbird) and others. Harlan’s all-embracing camera captures the scope and grandeur of the western vistas and Dunson’s enormous herd of cattle on the move, whether stampeding or crossing rivers; that same camera, sensitive and more intimate in the night photography, emphasizes the chiaroscuro of simple campfires or lantern light, demonstrating another instance of the superiority of black-and-white over color.

As one of the most honored film composers, Dimitri Tiomkin had no problem with Oscar nominations, receiving over twenty and winning four statuettes during his almost-forty-year career. His first important Western, with the help of Alfred Newman, though it pales beside his later epics, began with Gary Cooper’s The Westerner in 1940. Although both David O. Selznick’s overblown extravaganza Duel in the Sun in 1946 and Red River two years later showed what Tiomkin could do with the Western idiom, it wasn’t until High Noon in 1952 that the composer caught everyone’s attention as the man to call for this kind of score.

Thereafter, to prove it, Tiomkin would score The Big Sky, Strange Lady in Town, Giant, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Night Passage, Rio Bravo, Last Train from Gun Hill, The Unforgiven (1960), The Alamo (1960) and other titles. The War Wagon, his next-to-last feature film in 1967, was a Western.

Thereafter, to prove it, Tiomkin would score The Big Sky, Strange Lady in Town, Giant, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Night Passage, Rio Bravo, Last Train from Gun Hill, The Unforgiven (1960), The Alamo (1960) and other titles. The War Wagon, his next-to-last feature film in 1967, was a Western.

It was High Noon’s title song, “Do Not Forsake Me, O, My Darlin’,” sung by Tex Ritter and underscored in the orchestra throughout the film, that started a trend for title songs, a practice that soon became a cliché and set back the art of film scoring for years to come. And Tiomkin must share part of the blame. A number of his scores, regardless of film type, have a title song: “The Green Leaves of Summer” from The Alamo, the whistling tune from The High and the Mighty, “Thee I Love” from Friendly Persuasion, “So Little Time” from 55 Days at Peking, “Ballad of the War Wagon” from The War Wagon and “Wild Is the Wind” from Search for Paradise.

The plot of Red River is relatively simple, as scope and flexibility in Westerns aren’t all that broad. What set pieces, after all, are there?—gunfights, stampeding cattle, range wars, Indian attacks, cleaning up wild towns, saloon brawls and the like. Red River incorporates a number of these ideas, but the substance of the plot is centered around the cattle drive.

The plot of Red River is relatively simple, as scope and flexibility in Westerns aren’t all that broad. What set pieces, after all, are there?—gunfights, stampeding cattle, range wars, Indian attacks, cleaning up wild towns, saloon brawls and the like. Red River incorporates a number of these ideas, but the substance of the plot is centered around the cattle drive.

Leaving a wagon train and his girl (Coleen Gray), Thomas Dunson sets out on his own, along with trail hand Nadine Groot (Walter Brennan) and, tied to the back of a wagon, two steers. One night they fight off a few Indians and Dunson discovers on the wrist of one brave the bracelet he had given to his girl. Fears for her fate are confirmed when a young boy, Matthew Garth (Mickey Kuhn), with a cow in tow, emerges, incoherent and disoriented, from the night. He says he is the sole survivor of the wagon train.

After entering Texas—crossing the Red River—and declaring a huge tract of land as his own, Dunson encounters two Mexican riders who claim the land belongs to their boss Don Diego. When the outspoken one (Paul Fierro) draws his gun, Dunson kills him. After “reading over him,” he names his land the Red River D and brands the two steers. When Matt proves himself to be a man, he says, he will add an “M” to the brand.

After entering Texas—crossing the Red River—and declaring a huge tract of land as his own, Dunson encounters two Mexican riders who claim the land belongs to their boss Don Diego. When the outspoken one (Paul Fierro) draws his gun, Dunson kills him. After “reading over him,” he names his land the Red River D and brands the two steers. When Matt proves himself to be a man, he says, he will add an “M” to the brand.

Fourteen years pass. Dunson, Groot and Matt (grown and played by Clift) now have a massive herd, acquired through both purchase and rustling. One of the men who joins Dunson’s many cowhands (Harry Carey, Jr., Paul Fix, Hank Worden, Richard Farnsworth, Noah Beery, Jr., etc.) is gunfighter Cherry Valance (John Ireland, a troublesome, alcoholic actor whose part was reduced as a result). Since the defeated South can no longer afford his beef, Dunson decides to drive the herd to a railhead inMissouri.

A requisite stampede aside, troubles soon begin. From passing travelers, the men learn the railroad has reached Abilene, Kansas, but despite opposition Dunson prefers to press on to more distant Missouri. Along with his tyrannical, uncompromising leadership, Dunson is broke and cannot afford more supplies, and the men must subsist of a restricted diet of beef—and no coffee. When Dunson prepares to hang two men for deserting the drive, even Groot tells him he is wrong. With the support of the cowhands, Matt takes over, setting out for Abilene and leaving a wounded Dunson behind with his horse and some supplies. Matt has the bracelet. Dunson swears to kill him next time they meet.

A requisite stampede aside, troubles soon begin. From passing travelers, the men learn the railroad has reached Abilene, Kansas, but despite opposition Dunson prefers to press on to more distant Missouri. Along with his tyrannical, uncompromising leadership, Dunson is broke and cannot afford more supplies, and the men must subsist of a restricted diet of beef—and no coffee. When Dunson prepares to hang two men for deserting the drive, even Groot tells him he is wrong. With the support of the cowhands, Matt takes over, setting out for Abilene and leaving a wounded Dunson behind with his horse and some supplies. Matt has the bracelet. Dunson swears to kill him next time they meet.

Matt and his men defend a wagon train against Indians and he meets Tess (Joanne Dru). Naturally, they fall in love. Later, while Matt has gone ahead with the herd, Dunson reaches the wagon train and sees the bracelet on Tess’ wrist. When he tells her he wants a son, she offers to bear him one if he will abandon his pledge to kill Matt, but he will not relent.

Matt and his men defend a wagon train against Indians and he meets Tess (Joanne Dru). Naturally, they fall in love. Later, while Matt has gone ahead with the herd, Dunson reaches the wagon train and sees the bracelet on Tess’ wrist. When he tells her he wants a son, she offers to bear him one if he will abandon his pledge to kill Matt, but he will not relent.

Dunson reaches Abilene soon after Matt has arrived with the herd. Valance attempts to stop the gunfight between the two and Dunson kills him. The two go at it with their fists, until Tess shoots angrily at them, declaring it’s all a show, that they really love one another. The two are reconciled and Dunson draws the Red River D brand in the dirt; as he had said when Matt was a boy, he shows how the letter “M” will be added to the brand.

In Bordon Chase’s original Saturday Evening Post story, Dunson dies, but Hawks went for the Hollywood happy ending, which some critics have called unrealistic and contrived, a stumbling block in the flow of the plot. Another deviation, aside from general TV mutilations, is the two extant versions of the film, one with diary pages that comment on the cattle drive and the other with Brennan’s narration.

As Tiomkin’s score plays an important part in the emotion of the story and the success of the film, a few comments about this music specifically seem not only appropriate but necessary. The opulent main title music earns attention instantly, first with the call of horns, and then the sumptuous main theme in strings supported by a chorus, to the words “Settle Down.” Following the credits, the elevated letters simulating wood carving, the screen fills with the expanse of wide open spaces—a wagon train crossing the western plains—and, now, a third idea, the “cattle” theme. Soon, a banjo strums “Oh! Susanna.” The mood that the composer will maintain throughout the film is set.

Tiomkin varies this groundwork material and alternates or combines it with other tunes, such as the traditional American ballad “Bury Me Not on the Open Prairie” and the “revenge” theme for Dunson. In the film’s finale, that long-awaited showdown between Dunson and Matt, the “revenge” idea assumes dominance, becoming march-like and endlessly repeated, much as Tiomkin would do later in the “clock” sequence in High Noon, signaling the arrival of the noon train. In High Noon that sequence ends with the blast of a train whistle; here, more appropriately, there is the exuberant final statement of the main theme.

Tiomkin varies this groundwork material and alternates or combines it with other tunes, such as the traditional American ballad “Bury Me Not on the Open Prairie” and the “revenge” theme for Dunson. In the film’s finale, that long-awaited showdown between Dunson and Matt, the “revenge” idea assumes dominance, becoming march-like and endlessly repeated, much as Tiomkin would do later in the “clock” sequence in High Noon, signaling the arrival of the noon train. In High Noon that sequence ends with the blast of a train whistle; here, more appropriately, there is the exuberant final statement of the main theme.