“I feel I’ve had to go through the fire for some reason. Eleanor, it’s a hard way to learn humility, but I’ve had to learn it by crawling.”— Franklin Delano Roosevelt

With the recent premiere of the PBS eleven-hour The Roosevelts, An Intimate History, it seems appropriate to examine for a moment the 1960 movie Sunrise at Campobello, about Franklin Roosevelt’s struggle with the onset of polio. Of other Roosevelt interest, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s latest president-related book, The Bully Pulpit and the Golden Age of Journalism, has recently appeared in its softbound edition. It’s about William Howard Taft and FDR’s fifth cousin, Theodore Roosevelt.

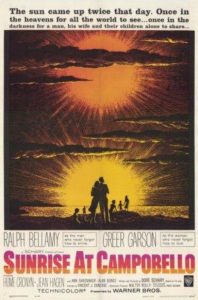

Sunrise at Campobello, based on Dore Schary’s play (and his screenplay), does an excellent job in setting not only the tone of the film, which is almost reverently maintained throughout, but the spirit that was Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.

These larger-than-life personalities are perfectly realized, first, by Ralph Bellamy, who, more than twenty years later, would again play the President in the miniseries The Winds of War and its sequel War and Remembrance, and then, second, by the London-born Greer Garson as FDR’s equally aristocratic wife. Miss Garson is better known, however, for her eight films with Walter Pidgeon, specifically Mrs. Miniver, and, otherwise, for Goodbye, Mr. Chips and Random Harvest.

The Warner Brothers film Sunrise at Campobello has unfortunately fallen into near-obscurity, available only in WB’s Archive Collection, where restoration is of secondary concern. This quiet, serious film—and long, at almost two and a half patience-testing hours—is totally actionless, heavily dialogued and generally stage bound. Only a few attempts have been made to shake off its interior settings by moving outside Roosevelt’s Hyde Park home where much of the story takes place. A “quiet” film, to be sure. It is, therefore, clearly out of favor with today’s trend toward non-stop action, one-dimensional characters, loud, booming sound, special effects and quick cutting and editing.

The relatively brief time span of the film covers from 1921, when FDR is stricken, until 1924, when, at the National Democratic Convention at Madison Square Garden, New York, he delivers the presidential nominating speech for Alfred E. Smith.

The film opens conventionally enough, the camera following a yacht as it tacks across the water. Franklin Roosevelt and his five children are on vacation at their Campobello Island home off the southeastern Canadian coast. Not surprising, FDR, a seasoned sailor and once Assistant Secretary of the Navy under Woodrow Wilson, is at the helm. They see a brush fire ashore and tie up, and, together, extinguish the flames. Then Roosevelt races his kids to the house where Eleanor is waiting.

Despite her suggestion that he change out of his wet clothes, he sits around reading the paper and his mail, talking politics, playing with his children and assigning parts in the evening’s production of Julius Caesar. “I shall read Marc Anthony,” he says, not without a certain animated haughtiness. “And you, Johnny (Tom Carty), will be the ‘mobs, the citizens and the sounds of battle.’ ” Turning to the housekeeper (Janine Grandel), he adds, “And you, Marie, you will be Julius Caesar . . . probably my greatest stroke of casting.”

Despite her suggestion that he change out of his wet clothes, he sits around reading the paper and his mail, talking politics, playing with his children and assigning parts in the evening’s production of Julius Caesar. “I shall read Marc Anthony,” he says, not without a certain animated haughtiness. “And you, Johnny (Tom Carty), will be the ‘mobs, the citizens and the sounds of battle.’ ” Turning to the housekeeper (Janine Grandel), he adds, “And you, Marie, you will be Julius Caesar . . . probably my greatest stroke of casting.”

Roosevelt is vibrant, animated, witty and, as always since he was born, full of life. That his vigor and good health could soon be taken from him is first suggested in a sudden stagger and a grab at his back. “Why, Franklin!” Eleanor says. “Must be a spot of lumbago,” he surmises. “No, I don’t feel feverish. Just suddenly”—he snaps his fingers—“like that——”

After going upstairs that night, as the PBS The Roosevelts narrator, Peter Coyote, intoned dramatically, “Roosevelt never walked again”—not without a cane, leg braces and the strong supporting arm of one of his sons. And that is what Sunrise at Campobello is all about, FDR’s slow—no, not recovery, for there would be none, although he always believed he would walk one day—rather, his bitter adjustment to his paralysis, even his overcoming it, if only spiritually and mentally.

When first struck that August, Roosevelt is not only unable to stand but unable to move his legs or get out of bed. He is at first in terrible pain, and his illness is misdiagnosed by several local doctors. Finally, a doctor from Boston correctly diagnoses infantile paralysis; even he errs in his prognosis that he “will recover almost completely.”

When first struck that August, Roosevelt is not only unable to stand but unable to move his legs or get out of bed. He is at first in terrible pain, and his illness is misdiagnosed by several local doctors. Finally, a doctor from Boston correctly diagnoses infantile paralysis; even he errs in his prognosis that he “will recover almost completely.”

One of the few semblances of “action” besides FDR’s wrestling with his boys on the front lawn of Hyde Park is Louis Howe’s (Hume Cronyn) strategy of moving his boss on a stretcher from his upstairs bedroom, across a bay in a launch to the mainland, then on a train to a New York City hospital. (Ironically, the removal of a window to get Roosevelt and his stretcher inside a Pullman coach would be repeated twenty-five years later at Warm Springs, Georgia, when his casket would be lifted through another train window for the return to Washington.)

Howe has been FDR’s constant companion and political advisor since 1909. The choice of Cronyn is the second masterstroke of casting after Bellamy as FDR, even more so than Garson as Eleanor. Cronyn has the thin, angular body and the lined face and wispy hair to approximate the actual man, who would die in 1936, during Roosevelt’s first term as President.

In his characterization, Cronyn is often animated and quirky, sometimes lapsing into an exaggerated Dutch accent or reciting FDR’s supposed favorite poem, “Invictus,” with theatrics and a pompous rolling of his r’s. What is not shown, however, is Howe’s sloppy hygiene and the ash-encrusted coat and tie from his constant smoking. He is always coughing and once lists “breathing” as one of his first priorities.

In his characterization, Cronyn is often animated and quirky, sometimes lapsing into an exaggerated Dutch accent or reciting FDR’s supposed favorite poem, “Invictus,” with theatrics and a pompous rolling of his r’s. What is not shown, however, is Howe’s sloppy hygiene and the ash-encrusted coat and tie from his constant smoking. He is always coughing and once lists “breathing” as one of his first priorities.

Roosevelt’s mother, Sara Delano, who refers to Howe as “that dirty little man,” is played by Ann Shoemaker. She is the only member of the 1958 Broadway production, aside from Bellamy, who appears in the film, although she had replaced the original Sara, Anne Seymour. Those scenes with FDR’s mother, who in life was a formidable, somewhat domineering personage, are often confrontational. Sara had felt that her son should accept his illness and become a country squire, attending to his stamp collection and naval prints. “I have no intention,” Roosevelt tells her, “of retiring to Hyde Park and rusticating.” These scenes provide some of the film’s most dramatic moments.

By comparison, FDR’s scenes with his wife are compassionate and intimate, though somewhat atypical of the man, as Roosevelt was not one to confide secrets. The portrayal in the film of their relationship as all warmth and roses is also a bit short of accurate, as the two had been living all but separate lives after the revelation, in 1918, of his affair with Eleanor’s social secretary Lucy Rutherfurd. There was, however, always mutual respect and affection between them, and Eleanor had been supportive of her husband during the early years of his polio.

By comparison, FDR’s scenes with his wife are compassionate and intimate, though somewhat atypical of the man, as Roosevelt was not one to confide secrets. The portrayal in the film of their relationship as all warmth and roses is also a bit short of accurate, as the two had been living all but separate lives after the revelation, in 1918, of his affair with Eleanor’s social secretary Lucy Rutherfurd. There was, however, always mutual respect and affection between them, and Eleanor had been supportive of her husband during the early years of his polio.

In fact, it was Eleanor who did, perhaps, more than any one in reminding the public that her husband was still a viable politician who had things to say. As Roosevelt himself remarked, “Between your speeches, Howe’s shenanigans and my statements, we’re keeping my head above water.” Present during all of her political and social speeches, Howe severely critiques her and, as best he can, coaxes the quirks from her high-pitched, easily excitable, sometimes giggly voice. In response to Howe’s query about the source of a “corset” joke she had shared with a women’s group, she attributes it to a dream. “Must’ve been a nightmare,” he says. When the two return to Hyde Park, turns out FDR had suggested the joke to Eleanor!

Franklin Roosevelt’s strong determination to walk, or at least to somehow circumvent his paralysis, is movingly shown in a number of scenes. In one, alone, he braces his wheelchair—the famous simple straight back chair without arms—against a sofa for stability, jams the two crutches under his arms and struggles to lift himself up and off the chair. He teeters, loses his balance and falls to the floor, face down. He struggles to a sitting position, literally beats and shoves his lifeless legs out straight, drags his backside to the chair, lifts himself into it with his powerful arms and shoulders, gathers the strewn crutches and starts all over again.

Franklin Roosevelt’s strong determination to walk, or at least to somehow circumvent his paralysis, is movingly shown in a number of scenes. In one, alone, he braces his wheelchair—the famous simple straight back chair without arms—against a sofa for stability, jams the two crutches under his arms and struggles to lift himself up and off the chair. He teeters, loses his balance and falls to the floor, face down. He struggles to a sitting position, literally beats and shoves his lifeless legs out straight, drags his backside to the chair, lifts himself into it with his powerful arms and shoulders, gathers the strewn crutches and starts all over again.

In another scene, he proudly demonstrates to Eleanor and Louis how, after dropping to the floor from his wheelchair, he can “climb” the staircase—sitting backwards, lifting his gluteus maximus, as he points out, from one step to the next, until he has reached the top. He calls his maneuver “the Roosevelt slide.” FDR had a fear of being trapped by fire and wanted to know he could reach a door or window. It was during one of these demonstrations in real life that Eleanor broke down for the first time during the initial crisis. In the film, the crying and running from the room occurs when she is struggling to read a children’s story to two of her boys.

Even with his disability and his efforts to play it down, Roosevelt wasn’t beyond saying, as he did on a number of occasions, “Well, I’m sorry. I have to run now,” or “Really, it’s as funny as a crutch.”

The last portion of the film is devoted to the events leading to Roosevelt’s nomination for President of Al Smith in 1924—the speculation between FDR and Louis as to why Smith (Alan Bunce) is paying a visit, the game-playing among the three men before Smith actually asks FDR to nominate him and the appearance of Roosevelt before the convention.

The last portion of the film is devoted to the events leading to Roosevelt’s nomination for President of Al Smith in 1924—the speculation between FDR and Louis as to why Smith (Alan Bunce) is paying a visit, the game-playing among the three men before Smith actually asks FDR to nominate him and the appearance of Roosevelt before the convention.

He has mastered the crutches and, with leg braces attached, he plods alone to the lectern, flinging one foot awkwardly ahead of the other. As the camera slowly pulls back across the crowd of delegates, he receives a thunderous applause. This was the occasion of his famous reference, not heard here, to Smith as the “happy warrior,” a phrase that dates, at least, to an 1806 Wordsworth poem, and no more original that FDR’s later first inaugural maxim “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

The movie is leisurely paced—and why not?: it was based on the Schary play—and directed by Vincent J. Donehue, who directed the 1958 Broadway premiere. And the six-time-Oscar-nominated cinematographer Russell Harlan maintains the film’s tempo, favoring long, uncut shots that last many minutes. This should infuriate the quick, slash-and-cut devotees of today. Composer of The Bride of Frankenstein and Sunset Blvd., Franz Waxman manages to find opportunities for sparkle amid the generally somber tones of the film, say, the theme for Hyde Park and Sara’s ride in the horse-and-buggy.

Just as Waxman found moments of gaiety among the darker tones on screen, so the plot has moments of comic relief, as when Mr. Brimmer (Lyle Talbot in his last feature film appearance before going into television) comes to update Roosevelt on establishing a dirigible route between New York and Chicago. Brimmer, as if his squeaky shoes aren’t annoying enough, paces back and forth between Howe and Roosevelt, spewing facts and statistics. All the while an unseen phone is ringing, unanswered. Howe seems to be making a move for the phone when FDR shouts, “Louis, why in the hell must you keep pacing up and down?”

Just as Waxman found moments of gaiety among the darker tones on screen, so the plot has moments of comic relief, as when Mr. Brimmer (Lyle Talbot in his last feature film appearance before going into television) comes to update Roosevelt on establishing a dirigible route between New York and Chicago. Brimmer, as if his squeaky shoes aren’t annoying enough, paces back and forth between Howe and Roosevelt, spewing facts and statistics. All the while an unseen phone is ringing, unanswered. Howe seems to be making a move for the phone when FDR shouts, “Louis, why in the hell must you keep pacing up and down?”

Later in another scene, Louis remembers, “With a little helium, I bet [Brimmer] could get to Chicago,” which prompts uproarious laughter from Roosevelt, who turns to an entering Eleanor and proclaims, “Louis is a monster.”

Missy Le Hand, FDR’s secretary, is played by Jean Hagen. Her role is a small one, and no indication is given that Roosevelt was a little smitten with her, or that she was in love with him all her life. Although beyond the focus of this movie, in real life she accompanied him on his numerous marine fishing trips, when Eleanor was absent. FDR’s son Jimmy, who assists him at the convention, is played by Tim Considine, who, ten years later, would be the soldier slapped by George C. Scott in Patton. Zina Bethune plays Roosevelt’s only daughter Anna, who, in the last years of his life, would conspire with her father to arrange his meetings with the then widowed Lucy Rutherfurd when Eleanor was away from the White House.

Missy Le Hand, FDR’s secretary, is played by Jean Hagen. Her role is a small one, and no indication is given that Roosevelt was a little smitten with her, or that she was in love with him all her life. Although beyond the focus of this movie, in real life she accompanied him on his numerous marine fishing trips, when Eleanor was absent. FDR’s son Jimmy, who assists him at the convention, is played by Tim Considine, who, ten years later, would be the soldier slapped by George C. Scott in Patton. Zina Bethune plays Roosevelt’s only daughter Anna, who, in the last years of his life, would conspire with her father to arrange his meetings with the then widowed Lucy Rutherfurd when Eleanor was away from the White House.

Remembered in the cliché as the actor who always lost the girl in the end, Ralph Bellamy also starred, often forgotten, in two detective series of the ’30s and ’40s, as Inspector Trent and Ellery Queen. As FDR would have in any circumstance, the actor dominates in his portrayal of the seemingly ever-happy, ever-witty, ever-smiling, ever-charming Roosevelt. He uses to best advantage all the famous props—the cigarette holder, the pince-nez and the wheelchair, which he handles adroitly, lifting himself from the mobile chair to a sofa. FDR’s mannerisms are brilliantly captured, too—that toss of the head, the upward tilt of the cigarette holder, the rolling diction, the toothy smile, the hearty laugh. Perhaps the uplifted, jutting chin is the one trait Bellamy uses to excess.

Roosevelt’s good nature and charm, charm being foremost among his personal traits, are forever at the forefront, along with the occasional moment when he uncharacteristically confides his despair to Eleanor. Ross McIntire, the White House physician, has observed: “More than any other person I have ever met, he had equanimity, poise and a serenity of temper that kept him on the most even of keels.” And yet, as James MacGregor Burns has written, “No biographer of Roosevelt, I think, feels that he really understands the man, nor, evidently, does any member of his family.”

Roosevelt’s good nature and charm, charm being foremost among his personal traits, are forever at the forefront, along with the occasional moment when he uncharacteristically confides his despair to Eleanor. Ross McIntire, the White House physician, has observed: “More than any other person I have ever met, he had equanimity, poise and a serenity of temper that kept him on the most even of keels.” And yet, as James MacGregor Burns has written, “No biographer of Roosevelt, I think, feels that he really understands the man, nor, evidently, does any member of his family.”

In another reflection on the enigma that was FDR, from William E. Leuchtenburg’s Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal: “Roosevelt’s public face—grinning, confident, but inscrutable—masked the inner man, and no one knew for certain what the man, in moments of reflection, really felt. . . . He seemed the compleat political man, the public self so merged with the private self that the President could no longer divorce them. . . . Others believed that beyond that gay reserve was an infinitely complex man whose detachment served his political ends, but who had an inner serenity . . . ”

For those readers interested in pursuing the always interesting life of FDR, and specifically the aspects of his illness, there is detailed reading in James Tobin’s The Man He Became, How FDR Defied Polio to Win the Presidency. Highly recommended, very well written and making the technical medical aspects easily understandable to the layman. Tobin examines the nature and the understanding of this disease polio at the time, how it affected victims in different ways, to varying degrees, recovery ranging from none at all (even death) to complete, that doctors then had no way of knowing how different individuals would fare or why.

Tobin hypothesizes a number of provocative “ifs”— if FDR hadn’t gone to the Boy Scout meet that day (where it is believed he contracted the polio virus), if he hadn’t fallen in the water while yachting (he was already, though, losing his perfect sailor’s coordination), if he hadn’t sat around in a wet bathing suit, if the later doctor had been called first instead of the others (with the totally wrong diagnoses), if there had been a greater sense of urgency among his family, if he had been given the polio serum, if there had been an early spinal tap and on and on. Even if there had been one or a number of interventions, the end result probably would have remained generally the same, that is, complete paralysis below the waist.

Tobin hypothesizes a number of provocative “ifs”— if FDR hadn’t gone to the Boy Scout meet that day (where it is believed he contracted the polio virus), if he hadn’t fallen in the water while yachting (he was already, though, losing his perfect sailor’s coordination), if he hadn’t sat around in a wet bathing suit, if the later doctor had been called first instead of the others (with the totally wrong diagnoses), if there had been a greater sense of urgency among his family, if he had been given the polio serum, if there had been an early spinal tap and on and on. Even if there had been one or a number of interventions, the end result probably would have remained generally the same, that is, complete paralysis below the waist.

Tobin cleverly points out—emphasizes, in fact—that the so-called “battle” over Roosevelt’s future, well portrayed in the film, was never between his wife and his mother, or between son and mother, but out of his own determination, that he was resolved to return to politics, and not become, as Sara wanted, an invalid country gentleman.

The film’s neglect is a shame, as it brilliantly, if in subtle, autumnal terms, conveys a few years in the lives of FDR and Eleanor—and, sadly, demonstrates that once, compared to the U.S.’s present state of political stagnation and mediocrity, there was a certain man of integrity, leadership and greatness. And a man who cared: “ . . . it seems to me,” Roosevelt says in the film, “that every human has an obligation in his own way to make some little stab at trying [to make the world better]. . . . The attitude of noblesse oblige is archaic. It’s another name for indifference.”

This praise goes with the understanding that there was during FDR’s presidency, and continuing on into the present, the anti-Roosevelt faction which regarded him then and regard him now as quite something else—devious, which he was; a “packer of the supreme court,” which he attempted; a proponent of socialism, which he well might have been; and a “destroyer of the country,” which he certainly wasn’t. During his presidency, he was so hated by the ultra-rich, who felt betrayed when FDR dared tax them in proportion to their wealth, that when their yachts were battered in a terrible storm, they would say, “It was blowing a real Roosevelt.”

This praise goes with the understanding that there was during FDR’s presidency, and continuing on into the present, the anti-Roosevelt faction which regarded him then and regard him now as quite something else—devious, which he was; a “packer of the supreme court,” which he attempted; a proponent of socialism, which he well might have been; and a “destroyer of the country,” which he certainly wasn’t. During his presidency, he was so hated by the ultra-rich, who felt betrayed when FDR dared tax them in proportion to their wealth, that when their yachts were battered in a terrible storm, they would say, “It was blowing a real Roosevelt.”

Either way, admired or hated, Roosevelt stands today as “a very great man,” as stated in the 1994 PBS American Experience series, and among the three or four greatest Presidents of the United States.