“I looked down from our bridge and saw our captain’s palm tree, our trophy for superior achievement . . . the award for delivering more toothpaste and toilet paper than any other Navy cargo ship in the safe area of the Pacific.”—— Doug Roberts (Henry Fonda)

“I looked down from our bridge and saw our captain’s palm tree, our trophy for superior achievement . . . the award for delivering more toothpaste and toilet paper than any other Navy cargo ship in the safe area of the Pacific.”—— Doug Roberts (Henry Fonda)

In The Caine Mutiny (1954), a U.S. Navy ship is isolated in the backwaters of World War II. “The USS Caine is a minesweeper,” Fred MacMurray tells young Robert Francis, playing a just-graduated ensign on his initial tour of his first ship. “We’ve been in combat a year and a half, and we’ve never swept a mine.”

In Mister Roberts, an outrageous comedy made the following year, the USS Reluctant is an old cargo ship, not an aircraft carrier, a battleship or even a minesweeper. During the waning months of the war the ship is assigned a “safe area.” Among its crew are an executive officer eager for a transfer to a theater of action, a tyrannical captain who refuses to endorse such a request and a mischievous ensign who avoids the captain, so much so that it is months before the officer first meets the man in charge of laundry and morale.

In both films, there is discontent aboard and an unhappy ending. The captain (Humphrey Bogart) of the Caine, for example, is relieved of command, not altogether his fault, as a navy lawyer, played by Jose Ferrer, tells the crew at film’s end. Aside from the personal conflicts written into the script of Mister Roberts, there was much antagonism and ill feelings during its making, a “war” of sorts, as the director and its major star actually came to physical blows.

The pre-production began auspiciously enough in early 1954. Director John Ford, whose name was still much before the public with such recent hits as The Quiet Man (1952) and Mogambo(1953), insisted he would only make Mister Roberts with long-time friend Henry Fonda, who had had a great success with the play, in an almost four-year run on Broadway.

The pre-production began auspiciously enough in early 1954. Director John Ford, whose name was still much before the public with such recent hits as The Quiet Man (1952) and Mogambo(1953), insisted he would only make Mister Roberts with long-time friend Henry Fonda, who had had a great success with the play, in an almost four-year run on Broadway.

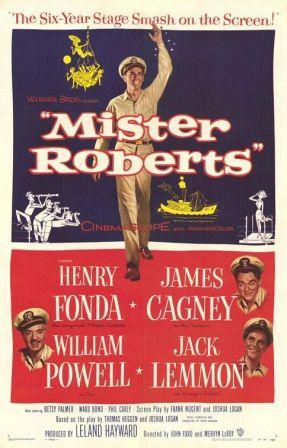

In an attempt to make Fonda, age 48, seem younger, producer Leland Hayward cast older actors as his co-stars—James Cagney, 55, and William Powell, 61. The one exception was a young, twenty-nine-year-old, up-and-coming actor, Jack Lemmon. And, of course, Ford carried over some of his stock company regulars—Ward Bond, Ken Curtis, Harry Carey, Jr. and Pat Wayne.

Ford and Fonda had made seven films together, even three in succession, Young Mr. Lincolnand Drums Along the Mohawk (both 1939) and The Grapes of Wrath (1940). Among their films that followed would be two of Ford’s best Westerns, My Darling Clementine (1946) and Fort Apache(1948).

Right from the start, Fonda realized that Ford’s adjustments to the script were deviating from the Broadway original. For one thing, the director, enamored of Lemmon, was adding scenes to emphasize his comic talents, gags with the actor tasting soup and showing the nurses who come aboard how he could fire a machine gun, then burning himself on the hot barrel.

Right from the start, Fonda realized that Ford’s adjustments to the script were deviating from the Broadway original. For one thing, the director, enamored of Lemmon, was adding scenes to emphasize his comic talents, gags with the actor tasting soup and showing the nurses who come aboard how he could fire a machine gun, then burning himself on the hot barrel.

The undercurrent of political differences played a part as well. This was the time of the House Un-American Activities Committee and most of the cast and crew leaned to the right, including Ford and the ultra-right Bond. Fonda leaned in the opposite direction, feeling the Committee was horribly against American principles.

Having finally taken enough, while filming on the island of Midway Fonda confronted Ford with his grievances. Just who started the fist fight remains uncertain. Lemmon seems a reliable source. While the cast and crew were staying in the bachelor officers’ quarters, he recalled passing a room in time to see Fonda “give [Ford] a hard push and throw him back on the bed.” Lemmon quickly returned to his room. Fonda later remembered that Ford had knocked him down at one point, probably before Lemmon arrived.

Having finally taken enough, while filming on the island of Midway Fonda confronted Ford with his grievances. Just who started the fist fight remains uncertain. Lemmon seems a reliable source. While the cast and crew were staying in the bachelor officers’ quarters, he recalled passing a room in time to see Fonda “give [Ford] a hard push and throw him back on the bed.” Lemmon quickly returned to his room. Fonda later remembered that Ford had knocked him down at one point, probably before Lemmon arrived.

Despite the brawl, filming continued as if nothing had happened, though tensions simmered beneath the surface. Sometime later Ford told Hayward that he could remove him from the picture if he wished. Hayward turned him down—too expensive.

Four days after the production had moved to Warner Bros. for interiors, Ford was hospitalized for a gall bladder operation. Rumors suggested this was a mere camouflage for Ford’s heavy drinking, but Betsy Palmer, one of the nurses in the film, saw the incision, which Ford insisted on showing her.

Three days later, Mervyn LeRoy resumed the direction, announcing to the cast, “I’m not going to tell you how to play the parts. . . . I’m just going to try to make the film Jack Ford would make.”

Three days later, Mervyn LeRoy resumed the direction, announcing to the cast, “I’m not going to tell you how to play the parts. . . . I’m just going to try to make the film Jack Ford would make.”

Much as that new ensign in The Caine Mutiny expected his new assignment would lead to glory on the high seas, Lieutenant “Doug” Roberts (Fonda) craves seeing some combat before the war ends. His requests for a transfer, however, are rejected by the belligerent captain, Lieutenant Commander Morton (Cagney), whose greatest concern is maintaining his exceptional career record.

Aboard is the opposite of the conscientious Roberts, a lazy, capricious ensign, Frank Pulver (Lemmon) who spends most of his time lounging on his bunk and avoiding the captain. The ship’s doctor, known simply as “Doc” (Powell), acts as a stabilizing influence on those under Morton’s command, though he is also constantly rejecting the many sailors’ excuses at sick call.

At a picturesque South Pacific island, a port captain awards the ship’s crew a much-needed liberty for their outstanding resupply work, transporting “crucial” war items such as toothpaste and toilet paper. Morton first refuses to grant the liberty, but so the crew may have it, Roberts agrees to cease his transfer requests and keep secret why he has stopped doing so.

At a picturesque South Pacific island, a port captain awards the ship’s crew a much-needed liberty for their outstanding resupply work, transporting “crucial” war items such as toothpaste and toilet paper. Morton first refuses to grant the liberty, but so the crew may have it, Roberts agrees to cease his transfer requests and keep secret why he has stopped doing so.

After all those months under the despotic captain, the men release their frustrations on the local town and are hauled back aboard in disgrace by the military police. The captain is reprimanded and the Reluctant ordered to leave port, which understandably incenses Morton.

Following news of the Allied victory in Europe, and knowing he may never see any action, Roberts vents his anger by throwing Morton’s prized potted palm tree overboard. Morton summons Roberts to his cabin and accuses him of the deed. Thanks to a microphone, accidentally left on, the crew learns why Roberts’ transfer requests had ceased.

Weeks later, when Roberts suddenly receives an official transfer, “Doc” confides to him that the crew had submitted a transfer request, forging Morton’s signature of approval. As he is leaving, Roberts receives from the crew the Order of the Palm, for “action against the enemy.”

Weeks later, when Roberts suddenly receives an official transfer, “Doc” confides to him that the crew had submitted a transfer request, forging Morton’s signature of approval. As he is leaving, Roberts receives from the crew the Order of the Palm, for “action against the enemy.”

Pulver, who has now been promoted to cargo officer, receives two letters a few weeks later. In the first, Roberts tells about his new combat experiences during the Battle of Okinawa. The second letter, from a Pulver friend who was aboard Roberts’ cargo ship, discloses that Roberts was killed soon after the first letter was mailed.

An angry Pulver, now perhaps assuming some of Roberts’ character, throws overboard the captain’s replacement palm, storms into Morton’s cabin and shouts, “Now what’s all this crud about no movie tonight?”

An angry Pulver, now perhaps assuming some of Roberts’ character, throws overboard the captain’s replacement palm, storms into Morton’s cabin and shouts, “Now what’s all this crud about no movie tonight?”

So what about the final on-screen results of the dual directors? The verdicts vary among writers and critics. Despite the film’s nomination for a Best Picture Oscar and Lemmon’s Best Supporting Actor award, two biographers in particular seem to reflect the generally negative consensus regarding the film. Scott Eyman, who wrote Print the Legend, The Life and Times of John Ford, wrote, “Mister Roberts has failed to sustain a reputation, coming to be regarded as a missed opportunity.”

And for Joseph McBride, author of Searching for John Ford, the film “turned into an outrageous debacle, the kind that could have ended the career of a lesser director [than Ford],” and “ . . . the underlying strength of the material was enough to carry the film despite its myriad deficiencies.”

Mervyn LeRoy was totally different from Ford, with none of the “mean, son-of-a-bitch malice” of his predecessor and not even remotely an autocrat—some say he was too easygoing as a director—and, in the end, didn’t make the film Ford would have made. He was perfectly willing to reshoot some of Ford’s work. Joshua Logan, who had co-scripted the play along with Thomas Heggen and had become a director in his own right (Picnic, 1955), filmed some retakes and eliminated the more outrageous of the gags Ford had devised for Lemmon.

Estimates vary, too, as just how much of the movie is Ford, how much is LeRoy. One of Ford’s favorite cinematographers, Winton Hoch, who shot the film, reported that ninety percent is Ford, surely a substantial overestimate. But more critically, is the difference apparent? In his thumbnail review of the film, Leonard Maltin summarized that the difference “certainly doesn’t show.”

Estimates vary, too, as just how much of the movie is Ford, how much is LeRoy. One of Ford’s favorite cinematographers, Winton Hoch, who shot the film, reported that ninety percent is Ford, surely a substantial overestimate. But more critically, is the difference apparent? In his thumbnail review of the film, Leonard Maltin summarized that the difference “certainly doesn’t show.”

I think it does show—not that it really matters. Seeing the film again recently, I was unimpressed; it wasn’t the “better” film I had remembered. The blaring of the Reluctant’s loudspeaker—the jarring “Now hear this! Now hear this!” at various times—is annoying enough on its own. Then there is Franz Waxman’s murky main title music: its subterranean and pessimistic tones suggest perhaps this Roberts fellow is a serial killer or, if the plot is to be naval, then a serious documentary on a submarine mission to end the war. The heaviness of the score that follows is inappropriate for a comedy.

Mister Roberts is, after all, just that, an unabashed comedy—and pretty fair as a comedy—much on the order of the free-for-all style Ford concocted in Donovan’s Reef in 1963. But except for the ever-professional Fonda, whose acting seems unaffected by the fist fight, the performances are so broad that at any moment, as Eyman writes, “you expect everybody to break into a musical number . . . ”

As the tyrannical captain, Cagney becomes a one-note character, barking his orders and insults with unnuanced bluster, truly one of his worst performances. Poor William Powell seems to go quietly along with it all, like Cagney keeping clear of the fray on set. Because this was Powell’s last movie, it’s been assumed, and reinforced by his own comments, that the experience devastated him, but he was also forgetting his lines for the first time in his career and experiencing a return bout with cancer.

Who’s left, then, but Lemmon. Hats off to him—it’s his show, for whatever part of this show he would have wished to take credit.