“My friends have overlooked my shortcomings, seen me through some dark days and brightened up the rest of them. I’m glad to have them. I’m honored to have them. I’m lucky to have them.” — Murphy Brown (Garner)

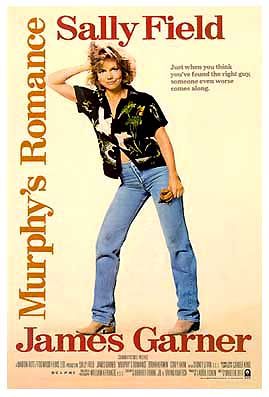

The most important reason to see Murphy’s Romance is for James Garner’s performance. It’s true that his fellow actors render admirable support—Sally Field as a poor, divorced mother; Brian Kerwin as her no-count ex, come calling out of the blue and arousing, at least momentarily, old feelings; and Corey Haim as her independent young son, much in need of a father image. In the other outstanding performance as a cantankerous codger, old-time actor Charles Lane is an undeniable delight in his one scene.

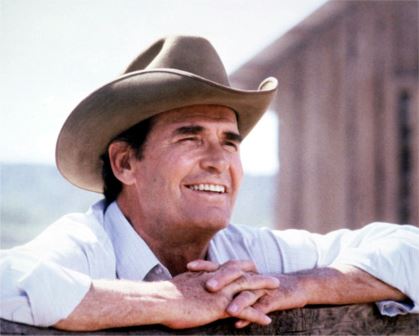

Garner as Murphy Jones, a small town’s only druggist, doesn’t swagger or dash about because there’s nothing arrogant or fleet-of-foot about him. Rather, he ambles through the lives of the innocent and good people around him, unassuming but very much a presence. He’s wise in so many ways, full of—not of himself—but of the knowledge of who he is, which is a man of common sense. Well-liked and decent all ’round, he’s no he-man out to prove something or anybody’s fool, any more than he tolerates fools.

It’s true that here Garner pretty much plays himself, such a nice guy in real life that that quality comes out naturally, instinctively. InMurphy’s Romance, the actor goes beyond himself, digging deeper than usual into his character—and into his own psyche, deepening on screen the image of both Murphy and himself. It’s hard not to like Murphy Jones, easy to see why a young widow, looking for a little stability in her life and seeing it in Murphy, is attracted to him.

James Garner earned his only Best Actor Oscar nomination for this film, beaten out by William Hurt in The Kiss of the Spider Woman.

In other films, Garner’s affability is reflected in the laid back scrounger in The Great Escape (1963), the polite suitor of Julie Andrews in The Americanization of Emily (1964) and the fun-loving PI in The Rockford Files TV series (1974-80). Later in life, he is totally convincing as the compassionate husband of Alzheimer’s victim Gena Rowlands in the TV movie, The Notebook TV (2004).

In other films, Garner’s affability is reflected in the laid back scrounger in The Great Escape (1963), the polite suitor of Julie Andrews in The Americanization of Emily (1964) and the fun-loving PI in The Rockford Files TV series (1974-80). Later in life, he is totally convincing as the compassionate husband of Alzheimer’s victim Gena Rowlands in the TV movie, The Notebook TV (2004).

Interesting to witness the tie-ins of various related films. Alzheimer’s sufferers would be the theme of two TV movies starring Richard Kiley, one in which he watches the gradual onset of the disease in his wife, Joanne Woodward, in Do You Remember Love (1985), and the other, Time to Say Goodbye (1997), in which he is the Alzheimer’s victim, taken care of by his wife Eva Marie Saint.

For her part, Sally Field also generally plays herself, delving less into her character that Garner does into his. There’s not the insight, either in acting intensity or in any desire to create a totally unique character, such as she exhibits in Places in the Heart (1984), winning a Best Actress Oscar for her portrayal, once again, of a young widow, now trying to survive as a farmer during the Great Depression. She won her first Oscar for her performance in Norma Rae (1979), and her director was Murphy’s Romance director Martin Ritt.

For her part, Sally Field also generally plays herself, delving less into her character that Garner does into his. There’s not the insight, either in acting intensity or in any desire to create a totally unique character, such as she exhibits in Places in the Heart (1984), winning a Best Actress Oscar for her portrayal, once again, of a young widow, now trying to survive as a farmer during the Great Depression. She won her first Oscar for her performance in Norma Rae (1979), and her director was Murphy’s Romance director Martin Ritt.

Ritt had previously paired her with Paul Newman in Absence of Malice (1981), where their chemistry is somewhat lukewarm. The chemistry with Garner in Murphy’s Romance is clearly palatable; Field said herself that the actor’s screen kiss—the only one in the movie, when he lifts her off the bar stool, smacks her one, tells her he’s not her analyst and directs her out the door—was the best she had ever received. Ritt’s most substantial director/actor collaboration was with Newman; the two made six films together: The Long, Hot Summer (1958), Paris Blues(1961), Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man (1962), Hud (1963), Outrage (1964) and Hombre (1967).

The team of Ritt, Field and screenwriters Harriet Frank, Jr. and Irving Ravetch had collaborated on the highly successful Norma Rae, and they could have well reasoned they could bring off Murphy’s Romance in much the same way. And the result is indeed a delightful movie—easygoing, a bit old-fashioned and only moderately predictable. Much is due to the charisma and likability of its two stars, but also to the natural, easy-flowing dialogue from Frank and Ravetch.

The team of Ritt, Field and screenwriters Harriet Frank, Jr. and Irving Ravetch had collaborated on the highly successful Norma Rae, and they could have well reasoned they could bring off Murphy’s Romance in much the same way. And the result is indeed a delightful movie—easygoing, a bit old-fashioned and only moderately predictable. Much is due to the charisma and likability of its two stars, but also to the natural, easy-flowing dialogue from Frank and Ravetch.

Emma Moriarty (Field) has moved into a dilapidated old farm house near a small Arizona town with her twelve-year-old son Jake (Haim). Together, they begin repairs, her intent to make it into a horse ranch. While she may not be good at making a lot of money or selecting the right husband, she does know something about horses.

At the one-and-only local pharmacy, she encounters the druggist, widower Murphy Jones (Garner), who also serves as what used to be called a “soda jerk,” certainly a proper term in his day, but now antiquated and marking any user as out of touch.

At the one-and-only local pharmacy, she encounters the druggist, widower Murphy Jones (Garner), who also serves as what used to be called a “soda jerk,” certainly a proper term in his day, but now antiquated and marking any user as out of touch.

Antiquated the man is not, and before she knows it, and perhaps sensing something decent and intelligent in Murphy, she’s attracted to him, long after the audience can tell they are going to get together. Soon she’s asking him for advice ranging from the flavor of her milk shake to what she should do with her life.

Emma is turned down at the bank for a loan, primarily because she’s a single woman. Because of his standards, Murphy refuses to give her any charity or an out-and-out loan, but he assists her indirectly. At a horse auction, for example, she advises him on a purchase, examining the animals’ legs and telling him to pass on several. When she sees a good horse, tells him to buy it and then asks where he’s going to keep it, he replies, “With you.” He’ll, of course, pay her to board the animal, and recommend that other townspeople do the same.

Emma’s ancient pickup truck is run off the road by a young kid (Hugh Burritt) and she ends up in the hospital unable to pay the bills. Murphy advises her and consoles her crying. He walks her around the halls, she quizzes him on his sex life—there is, already, a certain ease between them—and when they look in the window of the maternity ward, she asks, “Any of those yours?” “I told you,” he replies, “I go out of town.” When they have returned to her room, he informs her that her hospital gown had been open down the back.

Emma’s ancient pickup truck is run off the road by a young kid (Hugh Burritt) and she ends up in the hospital unable to pay the bills. Murphy advises her and consoles her crying. He walks her around the halls, she quizzes him on his sex life—there is, already, a certain ease between them—and when they look in the window of the maternity ward, she asks, “Any of those yours?” “I told you,” he replies, “I go out of town.” When they have returned to her room, he informs her that her hospital gown had been open down the back.

Murphy makes friends with her twelve-year-old son and shows him his 1930 Studebaker sedan, its bumpers and windshield plastered with placards representing his “causes”: “Stop Strip Mining” and “No Nukes.” Murphy extols the merits of the mint-condition car, the original leather interior and etched window glass.

When he takes Jake for a ride, being passed by every car on the road, they approach an old man on foot who flags down the car with a wave of his cane. He’s long-time town resident, Amos Abbott (Lane), and, from the back seat, he brags about his eighty years and his still joy of sex. The Studebaker approaches thirty m.p.h., much too fast for Abbott, who insists on getting out.

When he takes Jake for a ride, being passed by every car on the road, they approach an old man on foot who flags down the car with a wave of his cane. He’s long-time town resident, Amos Abbott (Lane), and, from the back seat, he brags about his eighty years and his still joy of sex. The Studebaker approaches thirty m.p.h., much too fast for Abbott, who insists on getting out.

As Emma is becoming more attracted to Murphy—asking repeatedly how old he is and never receiving a straight answer—her ex, Bobby Jack (Kerwin), appears out of nowhere and expects to resume their former life. While working in the barn together, he takes advantage of the moment. Emma is about to succumb to his kisses when she develops a sneezing fit, and then sets him straight, that it won’t be as it had been before.

Competition between Murphy and Bobby Jack for Emma’s attention erupts, first, at a town dance when they break in upon each other for Emma, and, later, at a birthday party for Murphy when the young fellow’s indolent swagger finally gets to Murphy.

“You are a miserable little son of a bitch, you know that?” Murphy says as the two are dumping garbage from the party. “I don’t know why she took you in the house. I’d bed you down with the dogs. And I’ll tell you something else, mister. You may be a lot younger and stronger, but you’re about to get your ass kicked from here to the state line. And I’m wearin’ the boots that can do it!”

“You are a miserable little son of a bitch, you know that?” Murphy says as the two are dumping garbage from the party. “I don’t know why she took you in the house. I’d bed you down with the dogs. And I’ll tell you something else, mister. You may be a lot younger and stronger, but you’re about to get your ass kicked from here to the state line. And I’m wearin’ the boots that can do it!”

The arrival of Bobby Jack’s girlfriend Wanda (Anna Levine) with their two infant twins proves the final straw for Emma and she sends him on his way. “Well,” she declares, “the party’s over, my friend. Someone just handed you the check.”

In the last scene of the film, in the evening twilight, Murphy stops by the farm once again. Emma comes outside to meet him. They embrace.

“I’m in love for the last time in my life,” he confesses.

“I’m in love for the first time in my life,” she replies. “Stay to supper, Murphy?”

“I won’t do that unless I’m still here at breakfast.”

“How do you like your eggs?”

As they walk into the house, he announces, voluntarily, without prodding, “I’m sixty.”

James Garner was, in fact, fifty-eight.