With a woman living two lives, her life could go either way.

With a woman living two lives, her life could go either way.

In Fire Over England (1936), his first film of note—a distinction nothing to do with him but to the first-ever pairing of screen lovers Laurence Olivier and Vivian Leigh—he was an Englishman spying for Spain in the sixteenth-century court of Elizabeth I and ends up dead. Already, with a few roles of either a villainous or, at least, a suspiciously duplicitous nature, his typecasting as a scoundrel seems to have been set by the time of I Met a Murderer (1939), when he does in a wife who killed his pet dog.

So it came to be that James Mason fell helplessly into this mold of expected uniformity and constraint. He becomes further straitjacketed in maleficent roles in The Man in Grey (1943) and The Seventh Veil (1945). In his first substantial hit, Odd Man Out (1946), he is an Irish rebel leader on the run from the police. The actor regarded it as his best—and favorite—role.

After murder also afflicts his character in his next film, The Upturned Glass (1947)—his last British film before a turn at Hollywood—Mason insisted on playing the good guy instead of the scheduled bad one in his first U.S. film, Caught.

Although the Brit receives top billing, he plays a somewhat secondary role to Barbara Bel Geddes in this, her fourth film. Best remembered as Miss Ellie Ewing Farlow in the long-running TV series Dallas (1978-1990), after which she retired, she is also James Stewart’s confidant and former fiancée in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958).

Although the Brit receives top billing, he plays a somewhat secondary role to Barbara Bel Geddes in this, her fourth film. Best remembered as Miss Ellie Ewing Farlow in the long-running TV series Dallas (1978-1990), after which she retired, she is also James Stewart’s confidant and former fiancée in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958).

With a subtle voice and a sweet, young-girl presence, she is artfully directed through extremes of quiet innocence and abject terror by the international German, Max Ophüls who had a penchant for “L”-named leading ladies.

As is the case in Caught. Leonora (Geddes), under the impulse of love, has married a power-hungry millionaire Smith Ohlrig (Robert Ryan), who does not love her.

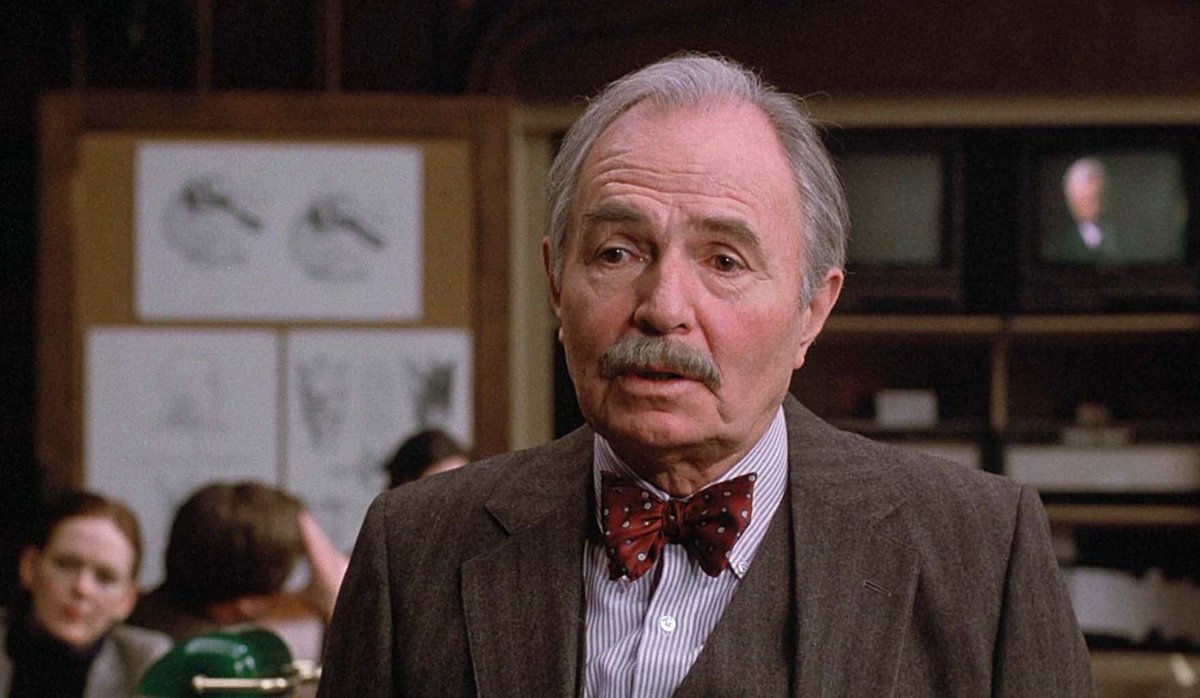

When Ohlrig becomes abusive, she leaves him, moving into a dingy apartment on New York’s Lower East Side and finding a job in a poor neighborhood as a receptionist in a medical clinic. Dr. Larry Quinada (Mason) is at first indifferent—and unintentionally insensitive—toward her, criticizing her typing, filing and even her fancy coiffure, a holdover from her “better” rich days.

She has a reconciliation of sorts with Ohlrig, thinking she might return to him, becoming pregnant. He attempts to use the child as leverage to force her to return permanently, but only as a power play, as his feelings toward her haven’t changed and he cares nothing for the child.

She has a reconciliation of sorts with Ohlrig, thinking she might return to him, becoming pregnant. He attempts to use the child as leverage to force her to return permanently, but only as a power play, as his feelings toward her haven’t changed and he cares nothing for the child.

She stands back when he, muttering “water, water, water,” has an angina attack, and denies him his medication, reminiscent of Bette Davis’ indifference when her husband, Herbert Marshall, begs for his heart medicine in The Little Foxes (1941).

Thinking she’s murdered him—he does survive—she phones Quinada for help and, under the stress, enters premature labor. At the hospital, the baby is stillborn. Now that there is no child, Ohlrig has lost his final control over Leonora and she is able to divorce him and marry Quinada.

The release date for Caught was three months following the preview showing. “For everyone concerned,” Mason remarked during the interim, “there was euphoria, [but] things returned to normal when the film opened in New York. No one came to see it.”

Caught is a much better film than audience turnout would indicate, much better indeed. Besides a screenplay by Arthur Laurents, who had written Anastasia (1956) and The Turning Point (1977), there is the cinematography of Lee Garmes (an uncredited Gone With the Wind, 1939, Since You Went Away, 1944, and The Big Fisherman, 1959). Garmes saturates the screen in deep noir shadows and finely etched black and white contrasts, especially during scenes in the Ohlrig mansion.

Caught is a much better film than audience turnout would indicate, much better indeed. Besides a screenplay by Arthur Laurents, who had written Anastasia (1956) and The Turning Point (1977), there is the cinematography of Lee Garmes (an uncredited Gone With the Wind, 1939, Since You Went Away, 1944, and The Big Fisherman, 1959). Garmes saturates the screen in deep noir shadows and finely etched black and white contrasts, especially during scenes in the Ohlrig mansion.

While Barbara Bel Geddes soon afterward turned mostly to television, James Mason hit his stride, and did some of his best, most diverse work in the 1950s—as the brilliant German tank general Erwin Rommel in The Desert Fox (1951), a spy in 5 Fingers (1951), the alcoholic husband of Judy Garland in A Star is Born (1954), a much-unappreciated performance as Captain Nemo in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), the suave—he mostly plays suave!—villain in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959) and a masterful turn to comedy in A Touch of Larceny (1960) with the lovely Vera Miles.

As with many long-careered actors, Mason hit the seemingly inevitable downhill slope. For him, it followed the ’50s, highlighted by a few outstanding movies and laudable roles along the way, the likes of Lolita (1966), The Blue Max (1966), Heaven Can Wait (1978), The Boys from Brazil (1978), Murder by Decree (1979)—all, again, illustrative of his versatility. The Verdict (1982), a courtroom drama opposite Paul Newman, is a last flicker—a rather strong flicker at that—of his acting tenacity in a first-class production.

As with many long-careered actors, Mason hit the seemingly inevitable downhill slope. For him, it followed the ’50s, highlighted by a few outstanding movies and laudable roles along the way, the likes of Lolita (1966), The Blue Max (1966), Heaven Can Wait (1978), The Boys from Brazil (1978), Murder by Decree (1979)—all, again, illustrative of his versatility. The Verdict (1982), a courtroom drama opposite Paul Newman, is a last flicker—a rather strong flicker at that—of his acting tenacity in a first-class production.

Although surrounded by some superb comics—John Cleese, Eric Idle, Peter Cook, Madeline Kahn and Marty Feldman—Yellowbeard (1987) turned out a bomb of a pirate comedy. It would have been excuse enough to quit the business, but Mason endured to the end, through a few more films and TV series. His final movie, The Assisi Underground (1985), was released the year after his death.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPHMoDpCHU8[/embedyt]