The games people play can lead to . . . murder!

The games people play can lead to . . . murder!

Clinton Green, a multi-millionaire Hollywood producer who had, a year before, lost his wife, Sheila, in a hit-and-run accident, invites six of his old friends—all from the movie industry—to spend a week with him on his yacht in the south of France.

A puzzle-game buff, he devises a most interesting diversion. He gives each of his guests an index card with a secret, what Clinton calls a “pretend” bit of gossip—one card marked informant, another ex-con, another shoplifter, etc.—that they cannot share with any other player. The attribute isn’t the cardholder’s own, Clinton instructs, but, in the course of the game, they are to discover who has which card. Each night, the yacht will anchor at a different port of call with clue-hunts ashore.

Clinton is playing a game of his own. All six guests aboard his yacht were at his party the night Sheila was killed, and he knows who ran down his wife. It’s his fiendish delight to watch and wait and enjoy the reactions, the jealousies, the secret concealments among his guests.

The concoction of this deft murder mystery—yes, there is murder afoot—came about by chance. Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins often hosted murder-mystery parlor games at their homes, and one guest, Herbert Ross, suggested they write a screenplay based on such game-playing. From the screenplay, it seemed only natural that Ross (The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, 1976, California Suite, 1978) should direct The Last of Sheila.

The concoction of this deft murder mystery—yes, there is murder afoot—came about by chance. Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins often hosted murder-mystery parlor games at their homes, and one guest, Herbert Ross, suggested they write a screenplay based on such game-playing. From the screenplay, it seemed only natural that Ross (The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, 1976, California Suite, 1978) should direct The Last of Sheila.

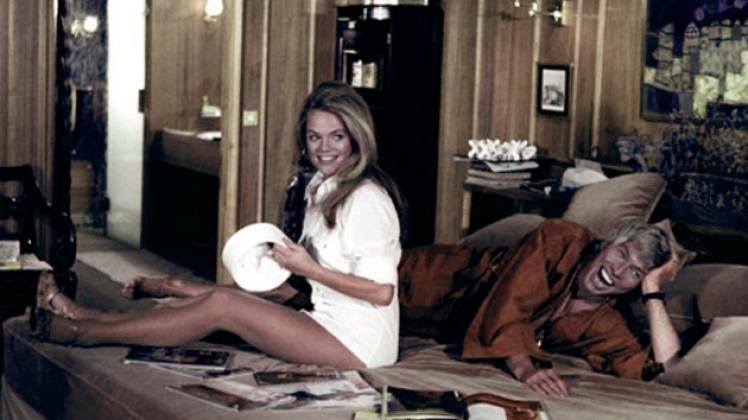

Maybe easier said than filmed. The production was plagued by numerous problems and setbacks. Worst of all, the shooting of a café scene was marred by an anti-Semitic bomb threat, though filming was completed safely. Filming aboard the yacht—actually producer Sam Spiegel’s—was so hectic, with the cramped quarters and the resultant seasickness among many of the cast, that time had to be idled away while a studio substitute set was built.

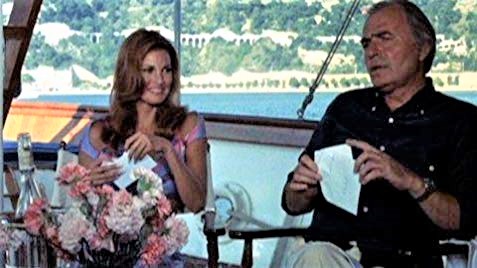

There were also personality conflicts, most trying the prima donna antics of Raquel Welch. Co-star James Mason called her “the most selfish, ill-mannered, inconsiderate actress that I have ever had the displeasure of working with.” Ian McShane concurred: “She isn’t the friendliest creature. She seems to set out with the impression that no one is going to like her.”

The leisure pace of the film, though not so leisurely as to spoil the mystery, is necessary for the audience to absorb all the clues, both on screen and in the dialogue. Paying attention is essential. It is best to see the film at least twice—first to simply relax and relish the goings-on and the uniformly excellent acting among the cast, then a second viewing to understand exactly what did go on in the complicated plot.

The leisure pace of the film, though not so leisurely as to spoil the mystery, is necessary for the audience to absorb all the clues, both on screen and in the dialogue. Paying attention is essential. It is best to see the film at least twice—first to simply relax and relish the goings-on and the uniformly excellent acting among the cast, then a second viewing to understand exactly what did go on in the complicated plot.

Not only is each character based on an actual Hollywood personality, but each represents a particular craft: excluding James Coburn as Clinton Green, Tom (Richard Benjamin) is a screenwriter, his wife Lee (Joan Hackett) a Hollywood heiress, Philip (Mason) a washed up director, Christine (Dyan Cannon) a talent agent, Anthony (McShane) a star-manager and his wife, Alice (Welch), an actress.

In the first night of the game, the card identity to discover is shoplifter, and Alice admits to being guilty. Because “shoplifter” proves to apply to one of the guests, suspicions arise that these crimes are not mere gossip, but truths apposite to each guest.

Only those who solve that night’s clue receive a point on Clinton’s scoreboard.

The next morning, while Christine is floating around the yacht on an inflatable raft near the stern, someone—the camera becomes that person—starts the engine. She is almost killed in the undercurrent created by the propellers.

The next morning, while Christine is floating around the yacht on an inflatable raft near the stern, someone—the camera becomes that person—starts the engine. She is almost killed in the undercurrent created by the propellers.

That night, the team of clue-seekers explores an abandoned medieval monastery for the identity of the homosexual cardholder. When Clinton fails to return to the yacht after the “game is over” sign has appeared, the group returns to the monastery and finds him dead from a blow to the head. The fragment of a blood-stained column lies nearby.

Back on the yacht, Tom confesses to being the homosexual, admitting to an affair with Clinton years earlier, and he suggests that they all present their cards. Each player does so and then confesses to his crime: Christine is the informant, Philip the “little child molester” and Anthony the ex-con. Most revelatory of all, Lee confesses to having killed Sheila that night while driving drunk.

As a kind of Sherlock Holmes, Tom theorizes there is something peculiar about Clinton’s death. It had been assumed that the column fragment had fallen on him during a storm, but the fragment was from the base of the column.

Later, while everyone else goes ashore to party—no time to mourn poor Clinton’s death by these apparently uncaring movie people—Philip, having no money to spend, stays on board. Tom returns alone and finds the director musing over the evidence—and pondering some new theories of his own. For one, Clinton, he says, wasn’t killed by a blow from the column fragment, but had been killed earlier.

Heretofore, James Mason has had a comparatively minor role, clearly smaller than either Benjamin’s or Hackett’s. Now he takes center stage in a long denouncement worthy of another fictional detective, Hercule Poirot. It seems he has discovered the secret of the index cards—and, in the climax of his discourse, the identity of the murderer.

Heretofore, James Mason has had a comparatively minor role, clearly smaller than either Benjamin’s or Hackett’s. Now he takes center stage in a long denouncement worthy of another fictional detective, Hercule Poirot. It seems he has discovered the secret of the index cards—and, in the climax of his discourse, the identity of the murderer.

Philip reminds Tom that before the voyage Clinton had his six guests line up on the wharf for a photo, positioning them carefully under the name of the boat, with each letter—S-H-E-I-L-A—corresponding to their card, i.e., “S” for shoplifter, “H” for homosexual, etc. In the one adjustment Clinton had to make, he added “little” before “child molester” to obtain the necessary “L.” But, by the way, how was it no one turned in a card for the “A”? Which might be, maybe, “alcoholic.” . . .

No, no! The Last of Sheila is too good a mystery, too complicated a whodunit, to carelessly disclose to those who have not seen the film the identity of the murderer, who, yes, does strike a second time. It is also a good mystery because the script plays completely fair with the viewer: there is no withheld information, no last-minute revelations. As in all mysteries that are planned and written by crafty novelists, or, in this case, by crafty screenwriters, the solution has been there all the time.

But, be advised, all isn’t what it seems.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPHMoDpCHU8[/embedyt]