Colonel Brandt: What will we do when we have lost the war?

Captain Kiesel: Prepare for the next one.

Sam Peckinpah’s films are known for predominantly three things. Notably they seem to delight in the depiction of violence and death, usually through the (sometimes over) use of slow-motion. His leading characters also usually fall into the category of ‘old souls;’ folks who are perhaps half a generation behind in holding on to older, more traditional- and perhaps currently underappreciated ideals.

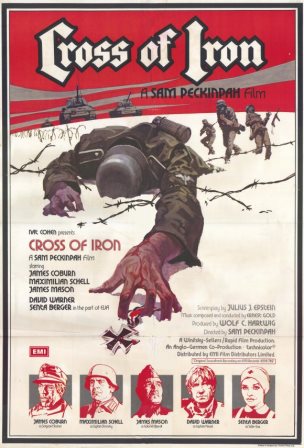

Peckinpah’s last major film was 1977’s epic Cross of Iron, set on the Eastern front in the middle of the Second World War. The story, told from the German perspective and centering around the life of a reconnaissance platoon. We aren’t at the doorsteps of German defeat just yet, but the average soldier sees it coming. At least, for a little bit longer, their fighting on Russian soil.

James Coburn, one of Peckinpah’s favorites, is Sergeant Steiner, the almost mythical leader of this platoon of mostly hardened veterans. But with casualties on the rise some appallingly young replacements are arriving to fill the dwindling ranks. The platoon’s life is undeniably hard, returning from each patrol to their timbered bunker, where Steiner leads by creating a somewhat familial environment and devout application of simple reality and common sense.

We’re also presented with Steiner’s new commanding officer, Prussian aristocrat Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell). Stransky’s feelings about the future of the war are unclear, but overall he seems uninterested in the outcome of the conflict as long as he can take home an Iron Cross- of which Steiner has two already. Stransky’s not depicted as a faithful Nazi (actually no one in the film is), but he’s definitely the stereotypical military man, simply obeying orders for his own vanity coupled with more than a touch of combat inexperience; though he’ll be the last to admit to it.

We’re also presented with Steiner’s new commanding officer, Prussian aristocrat Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell). Stransky’s feelings about the future of the war are unclear, but overall he seems uninterested in the outcome of the conflict as long as he can take home an Iron Cross- of which Steiner has two already. Stransky’s not depicted as a faithful Nazi (actually no one in the film is), but he’s definitely the stereotypical military man, simply obeying orders for his own vanity coupled with more than a touch of combat inexperience; though he’ll be the last to admit to it.

Last of the big three is James Mason as Colonel Brandt, Stransky’s superior and a quiet admirer of what Steiner brings to the group. Though Mason is rarely (if ever) bad in anything, he takes on the role extremely effectively, doing his duty but openly questioning the cause, most notably during his introduction to his new captain, Stransky.

Though slightly overshadowed by his earlier masterpiece The Wild Bunch, Cross of Iron is perhaps the among the greatest anti-war movies made. Among its admirers was Orson Welles, who called it the best war film he had seen since All Quiet on the Western Front, notably mentioning the films focus on the enlisted man rather than the high and mighty generals.

Though slightly overshadowed by his earlier masterpiece The Wild Bunch, Cross of Iron is perhaps the among the greatest anti-war movies made. Among its admirers was Orson Welles, who called it the best war film he had seen since All Quiet on the Western Front, notably mentioning the films focus on the enlisted man rather than the high and mighty generals.

Though many, especially at the time of its release, criticized the film it has since seen its critical acclaim increase of late. Many audiences in the United States were seemingly overwhelmed by the near constant barrage of explosions and flying bodies and other ‘sundries.’ Of course being in the theaters against the original Star Wars didn’t help. In Europe, however, the film did much better. Ironically (and most likely due to a more intimate relationship with the material situations) the film did exceedingly well in Germany, becoming one of the biggest earners of the era.

What many early viewers lamented was that the action was so pervasive that the plot was lost in the shuffle. Though there are tidbits of what one would term a plot, these viewers missed the point of Peckinpah’s imagery. His point is that war is so awful, so pointless, so omnipresent that everything else fades into the background at best, though nothingness is the more likely result.

What many early viewers lamented was that the action was so pervasive that the plot was lost in the shuffle. Though there are tidbits of what one would term a plot, these viewers missed the point of Peckinpah’s imagery. His point is that war is so awful, so pointless, so omnipresent that everything else fades into the background at best, though nothingness is the more likely result.

We see this even in the more dramatic points of the film, where Peckinpah masterfully shows the platoon (and to a lesser extent Stransky and Brandt themselves) developing ways just to get through the day. For the platoon this is simple birthday parties for fellow soldiers and fart jokes. Stransky’s obsession with the Iron Cross too is likely to large extent a mere distraction to enable him to simply survive (though surely prestige in the eyes of his family plays a roll as well).

Only Mason’s Brandt sees little need for such mere distractions. To him, war is life. He knows nothing else. Kiesel (David Warner) is of a similar disposition when he asks, “What will we do when we have lost the war?”

“Prepare for the next one.”

Peckinpah’s message is clear. We don’t all (at least most of us, anyway) want to be trapped in an endless cycle of fighting wars and then preparing for the next one. As ironic as it sounds, there was at the time (1943-45) perhaps a perception in the German populace that after losing Hitler’s war there’d be a mere respite before the next great conflagration. Most

had already been through the better part of two World Wars with twenty years of peace separating them.

There’s other bright lights in the casting besides Mason. James Coburn takes a turn in perhaps one of his most effective performance as the gritty and bare bones Steiner. Thankfully not engaging in any contrived German accent, Coburn’s Steiner becomes a beacon to his platoon, a man that in spite of all the retreats and shelling and death could still rally his mean to attempt the unthinkable against any odds. When Kiesel (taking on his role as almost a third party observer) states that Steiner, “Is a myth. Men like him are our last hope…and in that sense, he is a truly dangerous man;” we believe him.

There’s other bright lights in the casting besides Mason. James Coburn takes a turn in perhaps one of his most effective performance as the gritty and bare bones Steiner. Thankfully not engaging in any contrived German accent, Coburn’s Steiner becomes a beacon to his platoon, a man that in spite of all the retreats and shelling and death could still rally his mean to attempt the unthinkable against any odds. When Kiesel (taking on his role as almost a third party observer) states that Steiner, “Is a myth. Men like him are our last hope…and in that sense, he is a truly dangerous man;” we believe him.

Maximilian Schell also perfectly blends blind Prussian militarism with simple cowardice in presenting a more complicated picture than’s visible at first glance. In one of his better scenes, he is on the phone talking to Brandt while under fire. Within a few seconds he claims he’s both retreating and counterattacking in a crude attempt to guess what Brandt wants to hear.

Of final mention is don’t forget to look for the vintage Soviet T34 tanks used throughout the picture, courtesy of the Yugoslavian military who had kept them purely for cinematic purposes.