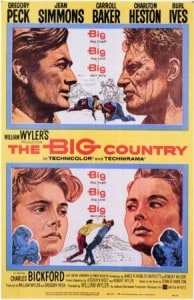

Big they fought! Big they loved! Big their story!

The Big Country was the film David O. Selznick tried to make with Duel in the Sun, but he lost his way with this super-gargantuan failure to top Gone With the Wind. In that famous scene in Duel, he seemed to wallow in the mud alongside Gregory Peck, who, with Charles Bickford, appears in both Westerns. But, in contrast, The Big Country is a clean, respectable, straightforward, uncomplicated, if not too original saga of the old West.

Peck is the top-billed star and co-producer, along with William Wyler, also the film’s director. Peck plays wealthy sea captain James McKay who has come west to marry his fiancée Patricia (Carroll Baker). The role of this decent, modest man, content with who he is and uninterested in proving anything to anybody, is very close to the actor’s own persona and qualities as a man. Peck’s ultimate role playing this sort of character would come in 1962 as the noble, wise and gentle Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Charlton Heston, something of a stuffed shirt in real life with totally contrary political views to Peck’s, was cast, appropriately enough, as an antagonistic ranch foreman. In his autobiography In the Arena, Heston writes that he emerged from filming with a sincere respect for his co-star. Both, it seemed, had witnessed the wiles of Wyler, the exacting standards that tested everyone’s endurance, even the reneging on a promised retake, as Heston relates.

Charlton Heston, something of a stuffed shirt in real life with totally contrary political views to Peck’s, was cast, appropriately enough, as an antagonistic ranch foreman. In his autobiography In the Arena, Heston writes that he emerged from filming with a sincere respect for his co-star. Both, it seemed, had witnessed the wiles of Wyler, the exacting standards that tested everyone’s endurance, even the reneging on a promised retake, as Heston relates.

In The Big Country, McKay has gotten himself into something by coming west—and it isn’t mud in this case. There is, however, some land with plentiful water called “The Big Muddy,” owned by schoolteacher Julie Maragon (Jean Simmons). By the accident of simply being present, McKay finds himself involved in a bullheaded, brutal fight over cattle watering rights between Pat’s father Major Henry Terrill (Bickford) and Rufus Hannassey (Burl Ives) and his three crude and cruel sons. One of the sons, Buck, is played by Chuck Connors, probably in his best role. The actor at the time was just beginning his long-running TV series The Rifleman.

In The Big Country, McKay has gotten himself into something by coming west—and it isn’t mud in this case. There is, however, some land with plentiful water called “The Big Muddy,” owned by schoolteacher Julie Maragon (Jean Simmons). By the accident of simply being present, McKay finds himself involved in a bullheaded, brutal fight over cattle watering rights between Pat’s father Major Henry Terrill (Bickford) and Rufus Hannassey (Burl Ives) and his three crude and cruel sons. One of the sons, Buck, is played by Chuck Connors, probably in his best role. The actor at the time was just beginning his long-running TV series The Rifleman.

From the first, McKay puts the locals off with his gentlemanly reticence and a different view from those around him of masculine ethics. He is, right off, unimpressed with a pair of dueling pistols Terrill gives him, saying they symbolize foolish heroics; his father had died in a pointless duel. Further, McKay refuses to be provoked when the Hannassey sons, led by Buck, harass him on an outing in a buckboard with Pat.

When Steve Leech (Heston) dares the newcomer to ride an unruly horse, Old Thunder, McKay declines. But while Leech and Terrill and his ranch hands are away avenging the Hannassey’s insult to Pat over the buckboard incident, McKay remains behind. After being thrown countless times, he eventually breaks the horse, telling the ranch hand Ramon (Alfonso Bedoya) that the feat is to remain a secret between them.

When Steve Leech (Heston) dares the newcomer to ride an unruly horse, Old Thunder, McKay declines. But while Leech and Terrill and his ranch hands are away avenging the Hannassey’s insult to Pat over the buckboard incident, McKay remains behind. After being thrown countless times, he eventually breaks the horse, telling the ranch hand Ramon (Alfonso Bedoya) that the feat is to remain a secret between them.

(Best remembered as the bandit killer of Humphrey Bogart in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Bedoya died before The Big Country was released, age fifty-three, having been a life-long alcoholic.)

Next morning, telling only Ramon, McKay, with a compass and map, rides off to find “The Big Muddy.” Being a sea captain, navigation is second nature. He is investigating the old, dilapidated house on the land when Julie, at first thinking him an intruder, approaches with a rifle. She shows him the stream flowing through her land. They talk. It’s easy to assume a romance has begun—understandable, as McKay is already seeing qualities in Pat he dislikes. McKay asks if Julie would sell the land to him; he would gladly share the water with both the Terrills and the Hannasseys. She agrees.

Thinking McKay lost, Terrill sends Leech and a party out to find him. One night, McKay nonchalantly appears in the campfire light of Leech and his men, claiming he was never lost. Later, in front of Pat and Terrill, Leech calls McKay a liar, that he was lost. McKay refuses to be provoked into a fight. “You’re gambling, Leech, that if we fight, you can beat me. And you’re gambling that if you beat me, Ms. Terrill will admire you for it.” Leech has obviously been taken with Pat, who rebuffs him on every occasion.

Thinking McKay lost, Terrill sends Leech and a party out to find him. One night, McKay nonchalantly appears in the campfire light of Leech and his men, claiming he was never lost. Later, in front of Pat and Terrill, Leech calls McKay a liar, that he was lost. McKay refuses to be provoked into a fight. “You’re gambling, Leech, that if we fight, you can beat me. And you’re gambling that if you beat me, Ms. Terrill will admire you for it.” Leech has obviously been taken with Pat, who rebuffs him on every occasion.

Pat, for sometime feeling that James McKay isn’t the man she once knew, is not only irritated but offended by his refusal to fight Leech and expresses doubts about their engagement. She is gradually shown to be a spoiled, selfish and self-centered young lady.

Early the next morning, McKay has a change of heart about fighting, awakens Leech in the bunkhouse and offers to “step outside.” In an open field, with no witnesses, they go at each other with their fists—one of the longest such fights on film—until, too exhausted to stand up, they call it a draw. “Tell me, Leech,” McKay asks, “what did we prove?” If nothing else, this dogged, presumed raw easterner has earned Leech’s respect, a respect that will eventually weaken his lapdog allegiance to Terrill.

Early the next morning, McKay has a change of heart about fighting, awakens Leech in the bunkhouse and offers to “step outside.” In an open field, with no witnesses, they go at each other with their fists—one of the longest such fights on film—until, too exhausted to stand up, they call it a draw. “Tell me, Leech,” McKay asks, “what did we prove?” If nothing else, this dogged, presumed raw easterner has earned Leech’s respect, a respect that will eventually weaken his lapdog allegiance to Terrill.

Pat learns from Julie that she has sold “The Big Muddy” to McKay—and, to boot, that he had tamed Old Thunder without telling her. Pat rides to town, as McKay has moved out of the Terrill mansion. When he tells her that he will allow both feuding families access to the water, she calls off their engagement.

In retaliation for Terrill’s men chasing his cattle away from “The Big Muddy,” Rufus Hannassey kidnaps Julie as bait to lure Terrill into an ambush. McKay hears about Julie’s capture and, along with Ramon and the case of dueling pistols, rides down the narrow canyon to the Hannassey ranch. He shows Rufus the signed deed to “The Big Muddy” and offers him watering rights, but Hannassey says the fight with Terrill is still on.

When Buck draws a gun on McKay during a fist fight—McKay is apparently catching on to the “cowboy way”—Rufus intervenes, saying if there are to be guns, they will be handled properly, the gentlemanly way, with the pistols McKay has brought. After the customary pacing-off, Buck shoots before the word “fire,” grazing McKay’s temple. It’s McKay’s turn to fire. With the pistol leveled at him, Buck drops to the ground in terror—not into any mud, just the dust of his own cowardice. McKay fires into the dirt. As McKay and Julie start to leave, Buck grabs a gun, aiming at McKay. His father shoots him, then cradles his dead son, cursing him all the while.

When Buck draws a gun on McKay during a fist fight—McKay is apparently catching on to the “cowboy way”—Rufus intervenes, saying if there are to be guns, they will be handled properly, the gentlemanly way, with the pistols McKay has brought. After the customary pacing-off, Buck shoots before the word “fire,” grazing McKay’s temple. It’s McKay’s turn to fire. With the pistol leveled at him, Buck drops to the ground in terror—not into any mud, just the dust of his own cowardice. McKay fires into the dirt. As McKay and Julie start to leave, Buck grabs a gun, aiming at McKay. His father shoots him, then cradles his dead son, cursing him all the while.

After a brief gunfight between Terrill’s and Hannassey’s men, Rufus calls a halt and challenges Terrill to a one-on-one shootout. In what seems like a just though expected outcome, the two kill each other. McKay and Julie ride off into . . . no, not a sunset: it’s beautiful, bright midday. And the vast expanse of a western landscape stretches before them.

After a brief gunfight between Terrill’s and Hannassey’s men, Rufus calls a halt and challenges Terrill to a one-on-one shootout. In what seems like a just though expected outcome, the two kill each other. McKay and Julie ride off into . . . no, not a sunset: it’s beautiful, bright midday. And the vast expanse of a western landscape stretches before them.

Burl Ives received a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role.

William Wyler is one of the best directors around and easily better than King Vidor, who received screen “credit,” if that’s the word, forDuel in the Sun. There were, however, numerous make-do directors, including William Cameron Menzies, William Dieterle, even Selznick himself. This torture of a film was shot on more than a dozen different locations, while Selznick dithered and dabbled with his ever-changing script.

William Wyler is one of the best directors around and easily better than King Vidor, who received screen “credit,” if that’s the word, forDuel in the Sun. There were, however, numerous make-do directors, including William Cameron Menzies, William Dieterle, even Selznick himself. This torture of a film was shot on more than a dozen different locations, while Selznick dithered and dabbled with his ever-changing script.

Certainly Duel has three great cinematographers—Lee Garmes, Ray Rennahan and Harold Rosson (all who did their best!)—but Franz Planer on The Big Country carries his own impressive credits: Roman Holiday, The Nun’s Story, Breakfast at Tiffany’s and personal favorite 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, shot, it’s rumored, with the only CinemaScope lens in Hollywood at the time.

Planer isn’t a specialist in Westerns, for his outdoor shots in The Big Country, though often spectacular, have none of the artist’s touch of a Winton C. Hoch in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and The Searchers, nor of a William H. Clothier in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Cheyenne Autumn, nor of any other John Ford photographer—Bert Glennon, Charles Lawton, Arthur Miller. After all, it was Ford’s eye (he wore a patch over the bad eye), more than his cameramen’s, that envisioned on screen those magnificent landscapes, especially of Monument Valley.

Planer isn’t a specialist in Westerns, for his outdoor shots in The Big Country, though often spectacular, have none of the artist’s touch of a Winton C. Hoch in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and The Searchers, nor of a William H. Clothier in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Cheyenne Autumn, nor of any other John Ford photographer—Bert Glennon, Charles Lawton, Arthur Miller. After all, it was Ford’s eye (he wore a patch over the bad eye), more than his cameramen’s, that envisioned on screen those magnificent landscapes, especially of Monument Valley.

If the plot of The Big Country is a blend of the routine, a mix of two basic ideas, the untested easterner out West and a feud between cattle ranchers, Jerome Moross’ music is the real breakthrough, the memory clincher, the ingredient that most sets this film apart from other Westerns.

And the score wastes no time. Wow, how it kicks off! Immediately! Like an esthetic slap in the face. Following a brief trumpet fanfare and set against excited, whirling strings, the main theme is literally thrown out unabashedly, vibrant and rhythmically full of syncopated accents. That the music, at the same time, ideally fits the screen image is incidental. Although there are other tunes, those for “The Big Muddy,” the Terrill ranch and a love theme, this opening melody is the most memorable, undergoing endless variations in support of any number of different scenes and sentiments. Sometimes the variations are so cunning and subtle as to be—if never unrecognizable, then often unrecognized.

At the beginning of many a Western, the camera following a train, a lone rider or a stagecoach or buckboard across a wide landscape is a cliché worn even beyond the threadbare. And, yes, in this case it is McKay’s stagecoach rattling over the hills and valleys. Not the coach, not the scenery—it is the music which captures the attention and suggests that something unusual is in store for the viewer—more correctly,the listener.

At the beginning of many a Western, the camera following a train, a lone rider or a stagecoach or buckboard across a wide landscape is a cliché worn even beyond the threadbare. And, yes, in this case it is McKay’s stagecoach rattling over the hills and valleys. Not the coach, not the scenery—it is the music which captures the attention and suggests that something unusual is in store for the viewer—more correctly,the listener.

Amazing to consider. At about this time, Dimitri Tiomkin had established himself as the composer, par excellence, of the Western score. The 1950s was perhaps his most productive decade for the genre—Giant, Friendly Persuasion, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Rio Bravo, Last Train from Gun Hill and other titles. Although Moross had written some movie scores before The Big Country, he was primarily an arranger, orchestrator and conductor. But here, in one swoop, even without the added color of the balladeer or the chorus of some Tiomkin scores, Moross has written something formidable, a challenge to all scores in the genre, including those by Tiomkin, Elmer Bernstein and Ennio Morricone.

The Big Country has conceivably the greatest Western score ever written, and Moross’ only Oscar nomination.

The Big Country has conceivably the greatest Western score ever written, and Moross’ only Oscar nomination.