“Our experiences today suggest that the territory is ripe for exploitation—you know the territory, and . . . er . . . I know how to exploit.” — Mordecai to Curley

“Our experiences today suggest that the territory is ripe for exploitation—you know the territory, and . . . er . . . I know how to exploit.” — Mordecai to Curley

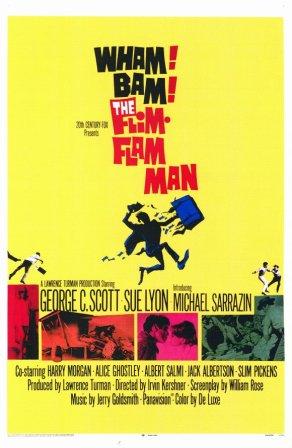

Among its other attributes, 1967 has the odd distinction of featuring at least four films set in the rural South. There’s the Georgia chain gang in Cool Hand Luke (filmed in California), two gangsters rampaging across Texas during the Great Depression ’30s in Bonnie and Clyde (actually filmed in Texas), racial bigotry toward a stop-over black police detective in Mississippi in In the Heat of the Night (filmed largely in Illinois) and traveling con artists in an unspecified Southern backwater in The Flim-Flam Man (filmed in Kentucky).

The first three films won at least one Oscar—respectively, Supporting Actor for George Kennedy, Supporting Actress for Estelle Parsons and Best Actor for Rod Steiger. In the Heat of the Night had the most wins, including Best Picture.

Perhaps because it was too much a comedy, bordering on the slapstick at times (comedies typically fare poorly at Oscar handouts), The Flim-Flam Man received nary a nomination—not for George C. Scott’s wily performance, nor for Jerry Goldsmith’s folksy score, the film’s two outstanding features, aside from its contagious, beguiling fun.

The movie has other positives: cinematography by Charles Lang (eighteen Oscar nominations, one win) and film editing by Robert Swink (Roman Holiday, The Boys from Brazil). Tight editing is, of course, essential in The Flim-Flam Man, juxtaposing and blending the slapdash action with the quiet, conversational moments of respite, where two traveling con artists share their philosophies and views on the foibles of the human condition.

The series of setups for the many unsuspecting dupes, “marks” or “pigeons” as known in the charlatan trade, are at the heart of the movie and form its theme, the gullibility and greed of mankind.

The series of setups for the many unsuspecting dupes, “marks” or “pigeons” as known in the charlatan trade, are at the heart of the movie and form its theme, the gullibility and greed of mankind.

Early in the film, two newly acquainted drifters find a place for the night in an abandoned, overturned railroad caboose. The elder of the two, Mordecai Jones (Scott), tells his rescuer and future partner (Michael Sarrazin), “Greed’s my line.” Then he clarifies himself: “Only cheat the cheaters, boy—you can’t cheat an honest man.”

Later in the film, after countless revelations of their fellowman’s avarice, young Curley, AWOL from the U.S. Army, will say, “I’ve been a-wondering if there’s such a thing left in this whole world as one, plain honest man. . . . I said most people are honest enough. Every single time, you show me what they is (sic) really like.”

But to backtrack to the very beginning of The Flim-Flam Man. Curley, obviously on the run, climbs aboard a passing freight train. Just before swinging up into a box car, he sees a man and suitcase being thrown from the box car ahead of him. In the first sign that Curley is more charitable than Mordecai will prove to be, he drops off the train to assist the elderly man. He helps him up, aids in collecting the scattered contents of the suitcase and the two wander off, together, through the woods.

But to backtrack to the very beginning of The Flim-Flam Man. Curley, obviously on the run, climbs aboard a passing freight train. Just before swinging up into a box car, he sees a man and suitcase being thrown from the box car ahead of him. In the first sign that Curley is more charitable than Mordecai will prove to be, he drops off the train to assist the elderly man. He helps him up, aids in collecting the scattered contents of the suitcase and the two wander off, together, through the woods.

After spending the night in the caboose, the two visit a general store. Mordecai performs the old three-card monte, moving the playing cards before a sucker who must pick the queen of hearts to win. With Curley working as the shill, the two are able to take the store owner (George Mitchell) for $42.

Back at the caboose, Mordecai and Curley are enjoying their profits when their repast of salami and ham sandwiches is interrupted by angry men from the general store. Now back on the road, the two continue their scams, “getting to know” the local folks—and exposing their avarice in the process.

Back at the caboose, Mordecai and Curley are enjoying their profits when their repast of salami and ham sandwiches is interrupted by angry men from the general store. Now back on the road, the two continue their scams, “getting to know” the local folks—and exposing their avarice in the process.

Next comes Mordecai and Curley’s biggest scheme, the centerpiece of the film, with its many nuances and extensions. Posing as a parson with his young friend, a car accident “victim” in need of a hospital, they steal a red convertible from a young girl, Bonnie Lee (Sue Lyon), and her mother (Alice Ghostley). “Well, I declare,” the mother says. “If the clergy ’round here’s gonna start stealin’ ever’body’s au-to-mo-bile——”

The county sheriff “Zeb” Slade (Harry Morgan) and his deputy Meshaw (Albert Salmi) recognize the red car whizzing by and give chase. Mordecai at the wheel manages to leave the nearby town in shambles, even smashing into Bonnie Lee’s father’s (Jack Albertson) new Dodge. “Yep, I’d say they’ll remember us in Clayton,” Mordecai muses.

The county sheriff “Zeb” Slade (Harry Morgan) and his deputy Meshaw (Albert Salmi) recognize the red car whizzing by and give chase. Mordecai at the wheel manages to leave the nearby town in shambles, even smashing into Bonnie Lee’s father’s (Jack Albertson) new Dodge. “Yep, I’d say they’ll remember us in Clayton,” Mordecai muses.

On foot again after the convertible crashes, and still pursued by the cigar-smoking sheriff and Meshaw, the two happen upon Doodle Powell’s (Jesse Baker) moonshine still and steal, this time, his 1948 Ford pickup. When the dirt road ends at a railroad track, Mordecai has Curley deflate the truck’s tires to half pressure and, wedging the truck on the rails, they are off down the track. This way of “making tracks,” as Mordecai brags, lasts only so long—until, faced with an approaching train, they initiate a quick right turn.

Next stop, at a general store Mordecai buys a few items, and affecting a German accent, dupes the proprietor (Woodrow Parfrey) into paying his bill with the fifty-eight bottles of whisky from the back of Doodle’s truck, adding bourbon to the sample bottle. Between the cost of Mordecai’s purchases and that of the moonshine, the owner owes $37.60.

Next stop, at a general store Mordecai buys a few items, and affecting a German accent, dupes the proprietor (Woodrow Parfrey) into paying his bill with the fifty-eight bottles of whisky from the back of Doodle’s truck, adding bourbon to the sample bottle. Between the cost of Mordecai’s purchases and that of the moonshine, the owner owes $37.60.

At another store, Mordecai sells the manager (Strother Martin) a $1 punch-board. Curley, knowing where the prize punches are, follows behind and wins $20, but the pièce de résistance of the scams is the “found wallet” ploy, known in the trade as the pigeon drop. With distraction and slight-of-hand, Mordecai and Curley reap a $500 profit from their mark (Slim Pickens).

The next morning, after Curley had been to see Bonnie Lee and they have discussed a future life together, Mordecai and his partner are awakened in their woodland hideout by Slade and Meshaw, and end up in jail.

The next morning, after Curley had been to see Bonnie Lee and they have discussed a future life together, Mordecai and his partner are awakened in their woodland hideout by Slade and Meshaw, and end up in jail.

But there’s one last trick, one last scheme, one last hoodwinking of the gullible and the culmination of all Curley has learned under the esteemed tutelage of this master con artist Jones. He proves himself a worthy student. Curley pretends to inform on Mordecai, regaling Slade with lurid tales of a murderer’s career, and, with the sheriff sufficiently distracted, escapes. He returns and places stolen dynamite around the jail, and, with a plunger, threatens to blow everybody up unless Mordecai is released and given an escape car. When Mordecai makes the pre-arranged three-ring call to a nearby phone booth, signaling he’s safe, Curley demonstrates that the plunger isn’t wired to anything. He’s jailed again. But Mordecai hasn’t even left town: he’s across the street in the shadows, observing all.

As the film began at a railroad track, so it ends at one. Mordecai, back on his own, stops at a railroad crossing and leans a presumably stolen bicycle against the wooden crossing signal. He waves as a freight train (between him and the camera) passes. When the train has passed, all that remains at the crossing is the bicycle.

As the film began at a railroad track, so it ends at one. Mordecai, back on his own, stops at a railroad crossing and leans a presumably stolen bicycle against the wooden crossing signal. He waves as a freight train (between him and the camera) passes. When the train has passed, all that remains at the crossing is the bicycle.

To support The Flim-Flam Man, Jerry Goldsmith has evolved a score that compliments and contrasts the humor and action; as good scores must do, this one never overwhelms. Much like Bernard Herrmann, he always adjusts his orchestral makeup and tonal palette according to the mood of a given film, the musical style different from picture to picture, from the steely, percussive Seven Days in May (1964) to the modernistic, atonal Planet of the Apes (1968) to the satanic chorus in The Omen (1976).

As The Flim-Flam Man is set in the backwoods South, so harmonica, banjos and honky-tonk piano are natural additions of color. The principal theme—the first music heard—is introduced in the main title as Curley helps Mordecai to his feet, with harmonica, banjos and an orchestral stick tapping out a jazz rhythm. This folksy theme could have come out of Copland in his populist or “Americana” style, and is often set against a contrasting lyrical theme, which represents the relationship between Curley and Bonnie Lee.

The big symphonic display comes in the frenetic, crazy car chase music—one car chase that isn’t gratuitous—where all elements are combined, even the recording of a regular piano in a lower key and speeding it up in playback to synchronize with the orchestra.

The big symphonic display comes in the frenetic, crazy car chase music—one car chase that isn’t gratuitous—where all elements are combined, even the recording of a regular piano in a lower key and speeding it up in playback to synchronize with the orchestra.

The supporting cast is all-around outstanding. Sarrazin is convincing as the young man who succumbs—but only temporarily—to the guile of Mordecai. He has a conscience. He wants to repay the damage in the two wrecked cars, plans to give himself up to the Army and later return to make his parents’ farm “a real show place.” And as he tells Bonnie Lee, “Tobacco, corn and kids is (sic) the principal crop in this county.” If a little idealistic, he is able to regain his sense of decency and, in the end, make the sacrifice for his friend and traveling companion, a sacrifice the viewer may suspect Mordecai, given the chance, would not make for Curley.

Lyon successfully moves from her roles as sexually precocious nymphs in Lolita (1962) and The Night of the Iguana (1964) to become a more innocent young girl, fervently stirred by this passing stranger. Morgan is outrageous as a hyperactive hillbilly sheriff, so good it’s easy to forget he is something of a caricature.

Lyon successfully moves from her roles as sexually precocious nymphs in Lolita (1962) and The Night of the Iguana (1964) to become a more innocent young girl, fervently stirred by this passing stranger. Morgan is outrageous as a hyperactive hillbilly sheriff, so good it’s easy to forget he is something of a caricature.

As for the actor who carries the weight of The Flim-Flam Man, Scott, with gray hair, bushy eyebrows and a hunched-over old man’s stance and gestures, is the clear standout. In the way he loses himself in a role and becomes entirely another person—the slick defense attorney in Anatomy of a Murder (1959), the overzealous general in Dr. Strangelove (1964) and a delusional Sherlock Holmes in They Might Be Giants(1971)—is best seen in his complete transformation into General George S. Patton in Patton (1970).