Longfellow Deeds and George Bailey. You probably know them by name, have seen them ’round and about, from time to time. If not, you probably know someone like them—more than one, if you’re lucky—a relative, a neighbor down the street, someone at work—a person, man or woman, who radiates generosity and kindness. Myself, I remember a special aunt and an old neighbor lady where I grew up—both the soul of goodness, who would have done anything for my family, or for me. For any one.

Longfellow Deeds and George Bailey. You probably know them by name, have seen them ’round and about, from time to time. If not, you probably know someone like them—more than one, if you’re lucky—a relative, a neighbor down the street, someone at work—a person, man or woman, who radiates generosity and kindness. Myself, I remember a special aunt and an old neighbor lady where I grew up—both the soul of goodness, who would have done anything for my family, or for me. For any one.

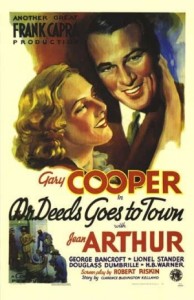

Longfellow and George were the heroes of two of director Frank Capra’s best films. Mr. Deeds Goes to Town is the older of the two, made in 1936. Longfellow Deeds, played by Gary Cooper, is a favorite son of Mandrake Falls, Vermont. A simple and idealistic man, he is quite satisfied to remain in his little backwater, writing poetry for greeting cards and playing his tuba. Although Deeds is shy around women, he nevertheless hopes to “save a lady in distress.”

Longfellow and George were the heroes of two of director Frank Capra’s best films. Mr. Deeds Goes to Town is the older of the two, made in 1936. Longfellow Deeds, played by Gary Cooper, is a favorite son of Mandrake Falls, Vermont. A simple and idealistic man, he is quite satisfied to remain in his little backwater, writing poetry for greeting cards and playing his tuba. Although Deeds is shy around women, he nevertheless hopes to “save a lady in distress.”

And then three gents from New York arrive to announce he’s inherited $20,000,000 from an uncle killed in a car crash. Deeds is off to the big city and into the ready clutches of people who want what he’s got—from his lawyer (Douglass Dumbrille) the legal control of his wealth, from the opera committee $180,000 to bail them out of debt and from a scheming newspaper reporter, Babe Bennett (Jean Arthur), an exposé on his outlandish character, all for a month’s vacation with pay.

When Deeds discovers his ideal woman, to whom he writes poetry, has been penning newspaper stories about his eccentricities—assaulting a literary figure, feeding donuts to a horse and chasing after fire engines—he emotionally shuts down during a sanity trial to determine his ability to handle his newly acquired riches. It’s only when Bennett admits, under oath, that she loves Longfellow that he awakens to defend himself. The judge (H. B. Warner) tells him, “You’re the sanest man who ever walked into this courtroom.” All ends well, as Capra movies of this vintage tend to do.

In my favorite scene in Mr. Deeds, Longfellow takes Babe Bennett, faking hunger and unemployment, to a restaurant and there they meet some literati who belittle his poetic prowess. After Longfellow has walloped one of the authors, another writer, Morrow, quirkily played by Walter Catlett, stands up to offer his own chin as a target.

In my favorite scene in Mr. Deeds, Longfellow takes Babe Bennett, faking hunger and unemployment, to a restaurant and there they meet some literati who belittle his poetic prowess. After Longfellow has walloped one of the authors, another writer, Morrow, quirkily played by Walter Catlett, stands up to offer his own chin as a target.

Excuse, now, a complete quote of that marvelous dialogue, minus Deeds’ brief insertions, as Morrow, drunk and teetering, delivers his lines in breakneck gusto, with the odd, florid phrases typical of a writer:

“Say, fellow, you neglected me and I feel very put out . . . You take me to the nearest newsstand and I’ll eat a pack of your postcards raw—raw. Oh, what a magnificent deflation of smugness! Pal, you’ve added ten years to my life—a poet with a straight left and a right hook. Delicious, delicious! You’re my guest from now on, forever and a day, even until eternity. You hop aboard my magic carpet and I’ll show you sights that you’ve never seen before. . . . Well, you’ll not only see [Grant’s Tomb and the Statue of Liberty], but before the evening’s half through, you’ll be leaning against the Leaning Tower of Pisa, you’ll mount Mount Everest. I’ll show you the pyramids and all the little pyramidees, leaping from sphinx to sphinx! . . .

“Pal, look, how would you like to go on a real old-fashioned binge? . . . Yeah, I mean the real McCoy. Listen, you play saloon with me and I’ll introduce you to every wit, every nitwit and every halfwit in New York. We’ll go on a twister that’ll make Omar the soused philosopher of Persia look like an anemic on a goat’s milk diet! . . . Fun? Listen, I’ll take you on a bender that will live in your memory as a thing of beauty and a joy forever.”

From the moment Morrow rises from the table and approaches Longfellow, until he exits left, the scene is one continuous take, which more about later. The viewer is hardly aware of the lack of cutting, so captivating is Catlett’s delivery and charisma, his body motions—the gyrations of the hand with the cigar, his arm around Longfellow’s shoulders at one point—and Deeds, on at least two occasions, pulling Morrow back from a pratfall.

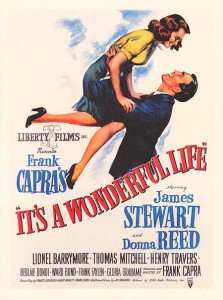

It’s a Wonderful Life, made ten years later, is about George Bailey, played by James Stewart, who lives in another obscure place, Bedford Falls. Unlike Longfellow, George wants out of his “crummy little town.” He wants to see the larger world and to “build airfields, skyscrapers and the longest bridge in the world.” Far from rescuing ladies in distress, Bailey wants to avoid being tied down in anyway, and marriage would clearly paralyze his hopes and dreams.

It’s a Wonderful Life, made ten years later, is about George Bailey, played by James Stewart, who lives in another obscure place, Bedford Falls. Unlike Longfellow, George wants out of his “crummy little town.” He wants to see the larger world and to “build airfields, skyscrapers and the longest bridge in the world.” Far from rescuing ladies in distress, Bailey wants to avoid being tied down in anyway, and marriage would clearly paralyze his hopes and dreams.

Deeds’ unwanted inheritance might have thrown him into a world for which he was ill-prepared, but Bailey’s deliberate attempts to escape into that same world are thwarted by a series of events and responsibilities which, quite the opposite, tie him to his home town. Rejected from military service because of a deaf ear (from saving his kid brother from drowning in an icy pond), he stays home, reduced to air raid warden while his sibling becomes a war hero. In spite of himself and counter to his ambitions, George marries his high school sweetheart Mary (Donna Reed) and is further tied down with four children.

When his father (Samuel S. Hinds) the bank president dies, George is compelled by civic pressure to assume the elder Bailey’s place to prevent a take over by “the richest, meanest man in town,” Henry Potter (Lionel Barrymore). From his introduction, Potter is the resident Simon Legree in the traditional Hollywood manner—riding in a black, hearse-like coach and dressing in black.

When his father (Samuel S. Hinds) the bank president dies, George is compelled by civic pressure to assume the elder Bailey’s place to prevent a take over by “the richest, meanest man in town,” Henry Potter (Lionel Barrymore). From his introduction, Potter is the resident Simon Legree in the traditional Hollywood manner—riding in a black, hearse-like coach and dressing in black.

Bailey is practically cocooned by people who love and appreciate him—his brother, his mother and his father—“a great man” George calls him. There are also Uncle Billy (Thomas Mitchell) at the bank and that high school sweetheart, who prefers him to rival Sam Wainwright, and the local policeman (Ward Bond) and cab driver (Frank Faylen), who join George in gawking at the town flirt (Gloria Grahame). His childhood boss the druggist (H. B. Warner again) gives him a suitcase for one of those planned escapes, this time to Europe, that never materialized.

The best part of Wonderful Life, at least for me, begins with the appearance of George’s guardian angel—no, not “Gabriel” as George once calls him, but Clarence, Clarence Oddbody, delightfully played by Henry Travers. Clarence has frustrated George’s suicidal plans by jumping from a bridge into the river, prompting George to save him. In the extended scene in the bridge tender’s shack, where the two are drying out, Clarence explains his origins, mission and “ASC” classification—Angel Second Class, without wings.

The best part of Wonderful Life, at least for me, begins with the appearance of George’s guardian angel—no, not “Gabriel” as George once calls him, but Clarence, Clarence Oddbody, delightfully played by Henry Travers. Clarence has frustrated George’s suicidal plans by jumping from a bridge into the river, prompting George to save him. In the extended scene in the bridge tender’s shack, where the two are drying out, Clarence explains his origins, mission and “ASC” classification—Angel Second Class, without wings.

The dialogue is relaxed yet incisive. Effective, too, are the subtle changes which occur after Clarence has granted George’s wish of never having been born. George doesn’t catch on, even when he can suddenly hear out of his left ear, when the bloody lip from an earlier brawl has healed, when the wet clothes on the line are suddenly dry and when a gust of snow blows open the door. (Technically, if George Bailey had never been born, he’d simply vanish, wouldn’t he? One doesn’t question the logic in a fantasy!) The bridge tender’s reactions to what he overhears—taking second looks and collapsing in his chair—are priceless. He finally flees, pausing to look back in bewilderment through the windows.