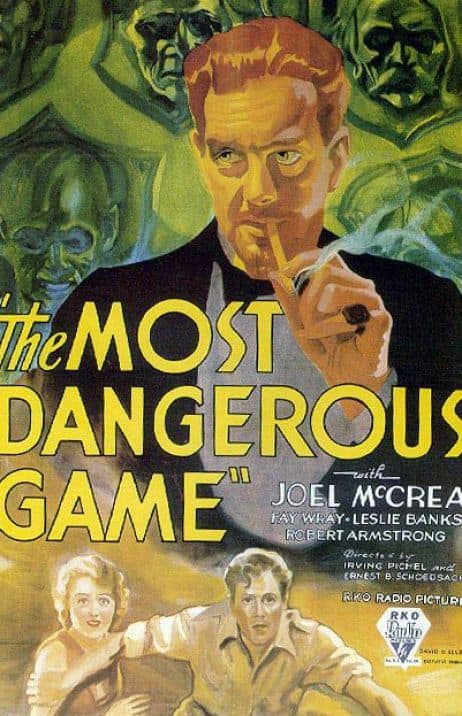

Count Zaroff is an avid hunter, but exactly what he hunts is rather unique, as his guests soon discover.

Aside from both being horror films, King Kong shares numerous similarities with The Most Dangerous Game, released the year before in 1932. Both are produced by David O. Selznick, then head of RKO. Both are scored by Max Steiner. Both utilize some of the same sets, most strikingly the large one for the jungle. Both films star Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong in leading roles and a number of now forgotten supporting players, Noble Johnson, James Flavin, Arnold Gray and Steve Clemente, in minor parts.

The theme of The Most Dangerous Game, man hunting human beings for sport, is based on a short story by Richard Connell in a 1924 issue of Collier’s magazine. Connell (1893-1949) went to Hollywood and quickly became a screenwriter, most impressively for Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941) and Two Girls and a Sailor (1944).

Presented at least three times as a radio drama, The Most Dangerous Game first appeared as an episode of Suspense, September 23, 1943, with Orson Welles as the notorious man hunter Count Zaroff, and Keenan Wynn as the American big game shooter.

Following 1932, the theme of Connell’s story surfaced in, first, two films of sharply contrasting quality. In A Game of Death (1946) an undistinguished cast, providing undistinguished performances, helps make a surprising dud for director Robert Wise. Much better, perhaps even superior to the ’32 Game, with a few additional plot twists and a more developed love story, Run for the Sun (1956) throws Richard Widmark, Trevor Howard and Jane Greer into the jungle. Now the chief villain is a Nazi.

Following 1932, the theme of Connell’s story surfaced in, first, two films of sharply contrasting quality. In A Game of Death (1946) an undistinguished cast, providing undistinguished performances, helps make a surprising dud for director Robert Wise. Much better, perhaps even superior to the ’32 Game, with a few additional plot twists and a more developed love story, Run for the Sun (1956) throws Richard Widmark, Trevor Howard and Jane Greer into the jungle. Now the chief villain is a Nazi.

In the next film incarnation of the man-hunting-man subject, Bloodlust (1961), it’s teenagers who become prey for a wealthy recluse. Then followed John Woo’s Hard Target (1993) with Jean-Claude Van Damme, Surviving the Game (1994) with Rutger Hauer, Pest (1997), a comic, bottom-of-the-barrel take on the story with Jeffrey Jones, and, most recently, The Eliminator (2004).

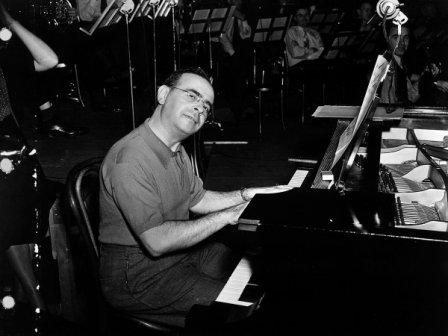

In any synopsis of The Most Dangerous Game, it would seem proper, even necessary, to include a running commentary on Max Steiner’s score. The music plays an integral part in the film, an equal participator, especially in the long jungle chase, where, with minimal dialogue, there is only the screen and the music.

The composer’s contribution here, coming in 1932, is early in the evolution of the extensive, nineteenth century style score that would, by the late 1930s and the further achievements of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, become standard procedure. King Kong, made at the same time as Game but released a year later, the delay owing perhaps to the time-consuming special effects required for Kong and the prehistoric creatures, has one of the first continuous, wall-to-wall scores in sound-on-film movie history.

The composer’s contribution here, coming in 1932, is early in the evolution of the extensive, nineteenth century style score that would, by the late 1930s and the further achievements of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, become standard procedure. King Kong, made at the same time as Game but released a year later, the delay owing perhaps to the time-consuming special effects required for Kong and the prehistoric creatures, has one of the first continuous, wall-to-wall scores in sound-on-film movie history.

Though music for Game occupies only about half of the film’s running time, the one sequence in the chase that lasts over four minutes demonstrates not only the competence and confidence of Steiner at this rather early stage in his film-scoring career, but shares a similar ambiance with the music he was simultaneously writing for King Kong. The composer would not reach his artistic peak until he joined Warner Bros. in 1936, beginning with The Charge of the Light Brigade, his inaugural score for that studio.

The main title is distinctive for the great iron door, and, unfortunately, the rather incongruously shy hand (why not a dramatic, insistent one?) that three times lifts the knocker, each timid knock bringing a new wipe of credits. First heard after the RKO telegraph-tower-atop-the-globe trademark is an ominous two-note motif on a solo horn, alternating with an uneasy disturbance in primarily the strings. Rather than the door opening, there’s a last wipe for a listing of the players.

The sinister music of the main title segues into a contrasting, soft lyrical theme, reminiscent, seven years later, of Steiner’s Dodge City score. On screen, it is night and a yacht is navigating a channel on the west coast of South America, guided by lights from several buoys.

The captain (William Davidson) is concerned that the location of the lights disagrees with his charts, but big game hunter Bob Rainsford (Joel McCrea) persuades him to sail on. The yacht runs aground and quickly sinks. After two companions are eaten by sharks, Rainsford swims alone to an island.

The captain (William Davidson) is concerned that the location of the lights disagrees with his charts, but big game hunter Bob Rainsford (Joel McCrea) persuades him to sail on. The yacht runs aground and quickly sinks. After two companions are eaten by sharks, Rainsford swims alone to an island.

After wandering through the jungle, he approaches a fortress-like edifice and knocks on the huge entrance door (from the main title). The door slowly opens and he steps into an enormous room as the score fades. A bearded man (Johnson) behind the door pushes it closed. Dressed in a white tunic, he doesn’t speak when Rainsford quizzes him.

Descending a long flight of stone stairs, a man in a tuxedo and smoking a cigarette on an extender says his servant, Ivan, is dumb. He introduces himself as an expatriate Russian, Count Zaroff (Leslie Banks in his talkie début). During World War I, the left side of his face was scared, an injury he adapts to his screen personas—for good guys, the left side is away from the camera; for villains, that side is toward the camera. Here he openly refers to the scare—“this head of mine”—and frequently touches his fingers to the mark on his temple, a sign of insanity, perhaps?

Rainsford meets two other guests of the count, Eve Trowbridge (Wray) and her inebriated, blasé brother Martin (Armstrong). Both, the count announces, were also stranded by a sinking ship. Eve seems to subtly warn Rainsford that things aren’t right here.

Rainsford meets two other guests of the count, Eve Trowbridge (Wray) and her inebriated, blasé brother Martin (Armstrong). Both, the count announces, were also stranded by a sinking ship. Eve seems to subtly warn Rainsford that things aren’t right here.

In the course of the evening, the four discuss the fine art of hunting. “Here on my island,” Zaroff says, “I hunt the most dangerous game.” “Tigers?” Rainsford asks. The count touches his temple. “My one secret. I keep it as a surprise for my guests, against the rainy day of boredom.” (The last phrase is a bit uncolloquial, clearly a writer’s line.)

After Rainsford and Eve retire for the night, the count offers to show Martin his trophy room. “I’m sure,” Zaroff says, “you’ll find it most . . . interesting.” (First time that adjective was used so ominously? Perhaps not!)

After almost twenty minutes of absence, Steiner’s score returns as Rainsford, from his bed, hears the sounds of dogs and a knock at the door. Eve says her brother is not in his room. The two creep downstairs, accompanied by stalking double basses and, at one point, the horn motif, now buried in the orchestral texture. Inside the trophy room, they behold a human head mounted on the wall. (Other heads and some gruesome dialogue by Zaroff were deleted after the premiere.) The count, carrying a candelabrum, enters with two servants bearing, on a stretcher, a dead Martin.

Now Rainsford learns which game Zaroff hunts, that Martin was his latest prey and that the madman has shifted the buoys to strand ship passengers on his island. By refusing to join the count in future hunts, Rainsford now becomes the hunted, provided with a woodsman knife and from sunset to sunrise to survive. Eve, rather than stay behind with Zaroff, joins Rainsford. The count himself won’t start “hunting” his two prey until midnight.

Now Rainsford learns which game Zaroff hunts, that Martin was his latest prey and that the madman has shifted the buoys to strand ship passengers on his island. By refusing to join the count in future hunts, Rainsford now becomes the hunted, provided with a woodsman knife and from sunset to sunrise to survive. Eve, rather than stay behind with Zaroff, joins Rainsford. The count himself won’t start “hunting” his two prey until midnight.

Rainsford first sets a Malay dead-fall or man-catcher, but Zaroff triggers the trip line with an arrow from his Tartar war bow, causing the dead tree trunk to fall harmlessly.

Next, a pitfall, with branches and brush over a crevice, fails to snare their pursuer. When Eve and Rainsford slip into a fog bank, making Zaroff’s rifle ineffective, the mad hunter signals on a hunting horn—the two-note horn motif from the score, no less. His dogs (Great Danes) are released, with Ivan holding the leashes to three or four of the animals.

Rainsford, at one point, sticks a sharp-ended branch in the ground, and Ivan is impaled upon it, leaving, now, Zaroff and only one servant in pursuit.

While most of the chase is music-accompanied, there are several long stretches where Steiner’s presence comes forth brilliantly. He gives the brass an amazing workout, especially the trumpets; the horn motif is sometimes heard as a solo, sometimes buried in the fabric of the orchestration. Much of the scoring, however, is standard action music, full of ostinato rhythms and various motifs in addition to the horn call, a montage suitable for any kind of chase, though nonetheless exciting. Some classical music “purists,” whoever they may be, would denigrate it out of hand as, “Oh, this is just film music,” as if that fact made it an automatic negative.

The chase climax, in screen action and music, occurs behind a waterfall. Rainsford kills the first dog, but Zaroff shoots and Rainsford and the second dog, locked in a death struggle, fall into the plunge pool of the falls. With a dramatically lighted close-up with deep shadows, the count’s eyes glare as he takes Eve back to the fortress as his prize. “Only after the kill,” Zaroff had said at the beginning of the hunt, “does man know the true ecstasy of love.”

The chase climax, in screen action and music, occurs behind a waterfall. Rainsford kills the first dog, but Zaroff shoots and Rainsford and the second dog, locked in a death struggle, fall into the plunge pool of the falls. With a dramatically lighted close-up with deep shadows, the count’s eyes glare as he takes Eve back to the fortress as his prize. “Only after the kill,” Zaroff had said at the beginning of the hunt, “does man know the true ecstasy of love.”

The supposedly triumphant count now plays a waltz on his piano, a Steiner tune containing, persistently, the horn motif. Soon after Zaroff asks a servant to bring Eve to him, he is confronted by Rainsford, who says he took a chance and fell with the dog; it was the dog the count shot. Zaroff admits defeat, tossing the keys to the boathouse, but then pulls a pistol from a table drawer. The two men struggle, accompanied by Steiner’s fight music, and Rainsford stabs his opponent with one of his arrows. Even as Eve and Rainsford are fleeing in the motorboat, the wounded count staggers to a high window with his Tartar war bow, but dies and rolls out the window before he can shoot.

The small cast generally renders convincing performances, especially Joel McCrea, always excellent as the stalwart man of intelligence, and Fay Wray as the damsel in distress. For the chase, her nightgown attire, hardly improper today, would have been deemed too risqué if the then in operation Production Code had been doing its job, though strict enforcement did begin in 1934. There are no moments for an authentic romance between the two leads, so tied are they to the plot of their staying alive.

Armstrong often overacts, especially when he’s playing drunk. It’s hard to know whether he is the standard one-note comic relief in a generally humorless film or a bona fide actor trying to be serious. He may well be the weakest link among the leading stars.

Leslie Banks is the standout, if for no other reason than he, too, overacts, a little campy, but that somehow colors his identity as a suave, cultured villain. His Shakespearean training, with the somewhat old-fashioned cadenced tones, is misplaced, at least in this case. In Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1945), he is relegated to being the chorus.

Leslie Banks is the standout, if for no other reason than he, too, overacts, a little campy, but that somehow colors his identity as a suave, cultured villain. His Shakespearean training, with the somewhat old-fashioned cadenced tones, is misplaced, at least in this case. In Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1945), he is relegated to being the chorus.

A MUSIC NOTE – For those interested, the excitement of both the film and the music may be “relived,” so to speak, through a NAXOS CD (8.570183), the only modern (2001) recording available of the Most Dangerous Game score. The disc is highly recommended for the excellent playing of the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, the sound engineering by Edvard Shakhnazarian, the extensive notes by Bill Whitaker and a generous thirty-two minutes from the score. Also included are forty-five minutes from another Max Steiner score, the 1933 Song of Kong, the sequel to King Kong.