“I never knew the big son of a bitch could act.”

When deciding which five Westerns should be discussed, be singled out as ones of some distinction, not over-analyzed and at the same time deserving of recognition, two came immediately to mind. The titles I wrote on a piece of paper both starred John Wayne, and, upon close examination, I discovered they both were directed by John Ford. Hum, a “theme”? John Ford/John Wayne Westerns? Sure, tempting—and obvious. Too obvious—and, besides, a study of that pairing has been done, in any number of books and film specials. So—a bit of a compromise, to make things more diverse: the five Westerns would all star big guy Wayne, but only two would be directed by Mr. Ford.

But why five Westerns? Why not more? Why not a Top Ten? No, only five. But which five? I didn’t want them all to be great, though, clearly, to fit within the guidelines already set, none could be mediocre, either. A few more minutes of memory search and three more titles appeared on my paper. Good enough. Not a big fan of the Western genre, or so I’d thought, all five—well, surely four—were among my favorite movies, the kinds I could watch over and over, without fatigue, films still possessed of enough originality, enough sparkle, enough look-forward-to moments, enough photographic and acting highlights to remind me just why these five films . . . er . . . these four films had endured so pleasantly in my memory.

No, I shan’t list them all flat out. Rather, in turn, as I come to them. I will say at the outset, however, that one is kind of a wild card, a joker, not intentionally so, only in retrospect; now, it’s appropriate as a contrast to the other four, among which it might seem out of place. And speaking of contrasts, another of the films—one of the first two written on that piece of paper—is a masterpiece, out of place, too, in quite a different way, but which I will allow, though it is much written about. Unlike the other four, which could pass, and at the time did, as diverting Saturday afternoon entertainments of cowboys/soldiers against renegade arms smugglers or Confederates or Benito Juarez insurgents or land grabbers, the single masterpiece, though with the traditional Western villains, the Indians, is as dark as any Shakespearean tragedy. Unlike the others, it has an unattractive “hero” and an angry, uncomfortable subplot.

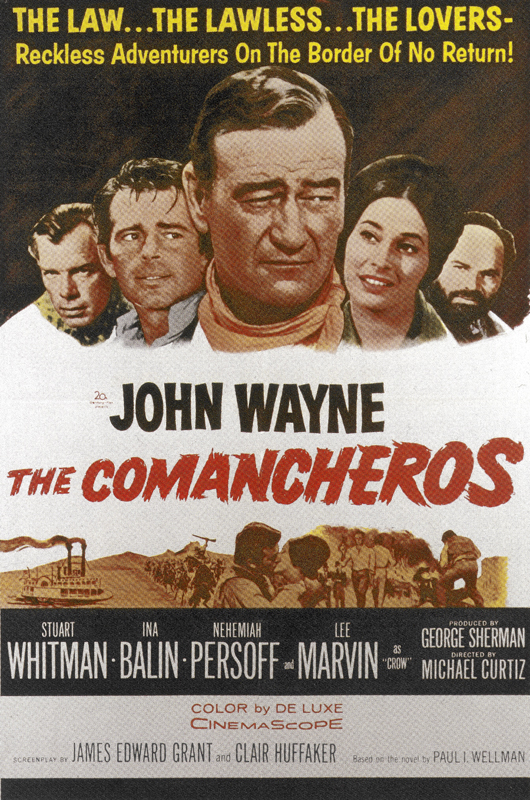

The Comancheros (1961). Yep, that’s the first Western—not in quality or date order, neither the joker nor the masterpiece, just listed first. Starting with a punch. Each of the five films has something that marks it for good or for bad, or as some kind of milestone. In this case, The Comancheros was director Michael Curtiz’ last picture. One of the most versatile and productive of his breed, Curtiz had directed Errol Flynn in four of the genre, plus the Western-like The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), before the two had had enough of each other and parted company. Due to Curtiz’ illness, Wayne had a hand in some of the direction, though to what extent is hard to know; The Alamo, with which he did make his directorial début, came the year before.

The Comancheros (1961). Yep, that’s the first Western—not in quality or date order, neither the joker nor the masterpiece, just listed first. Starting with a punch. Each of the five films has something that marks it for good or for bad, or as some kind of milestone. In this case, The Comancheros was director Michael Curtiz’ last picture. One of the most versatile and productive of his breed, Curtiz had directed Errol Flynn in four of the genre, plus the Western-like The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), before the two had had enough of each other and parted company. Due to Curtiz’ illness, Wayne had a hand in some of the direction, though to what extent is hard to know; The Alamo, with which he did make his directorial début, came the year before.

As with most Curtiz films, and with whatever degree from Wayne in this case, The Comancheros is fast-moving and with a more complicated plot than most Westerns. Paul Regret’s (Stuart Whitman) romancing a mysterious woman (Ina Balin) is ended—only interrupted, actually—by his being arrested, always an inconvenience, by Texas Ranger Captain Jake Cutter (Wayne). Balin as the love interest, like Regret’s arrests, comes and goes, maintaining a consistent, if not overly commanding presence.

The relaxed antagonism, later friendly bantering, between Jake and Paul runs charmingly throughout. Before they become buddies, united against the comancheros, Jake is forever reminding Paul, “I’m not your friend,” and addressing him as “mon-sewer,” perhaps mocking Whitman’s poor showing as a Frenchman, never attempting an accent, though he pauses once to sing “Frère Jacques” to a little girl.

Two other actor stand-outs, here stealing scenes from their co-stars, are studies in contrast, one over the top, the other restrained. Lee Marvin, with a half-scalped head and a pigtail, plays the drunk, the gambler, the loud mouth. A similar role earned him an Oscar for Cat Ballou in 1965. And the wheelchair-bound leader of the comancheros, that secret band of gun traders, is Nehemiah Persoff—calmly cruel, whacking his cane on a table to demonstrate his controlled meanness.

Two other actor stand-outs, here stealing scenes from their co-stars, are studies in contrast, one over the top, the other restrained. Lee Marvin, with a half-scalped head and a pigtail, plays the drunk, the gambler, the loud mouth. A similar role earned him an Oscar for Cat Ballou in 1965. And the wheelchair-bound leader of the comancheros, that secret band of gun traders, is Nehemiah Persoff—calmly cruel, whacking his cane on a table to demonstrate his controlled meanness.

The action scenes have, at least, a surface punch, with a few visual blemishes—obvious dummies which fall sack-like, rear screen projection and the same promontory appearing at two different locations. A decided plus is Elmer Bernstein’s music, whose main tune is more attractive, and better suited for development, than the famous theme from his score for The Magnificent Seven. This might well be the best music in the five films, although the score for that one masterpiece, still to come, suggests close competition.

An easy three stars, out of a possible four, for The Comancheros, diverting entertainment at its best.

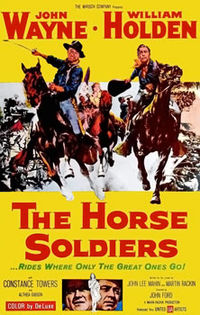

Few, perhaps, will deny that the next film is a few notches up, the first of the two by the greatest of all Western directors, John Ford. The Horse Soldiers (1959) is another of his cavalry adventures, though not part of, nor equal to, that great trilogy, Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande, all starring Wayne. For essentially a small film, Soldiers has the sweep of a big one—single file cavalry crossing a ridge, a landscape of railroad tracks being destroyed, a trek through a swamp and an attack by military school cadets (“Why, those’re nothing but children! They’re school boys!”).

Few, perhaps, will deny that the next film is a few notches up, the first of the two by the greatest of all Western directors, John Ford. The Horse Soldiers (1959) is another of his cavalry adventures, though not part of, nor equal to, that great trilogy, Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande, all starring Wayne. For essentially a small film, Soldiers has the sweep of a big one—single file cavalry crossing a ridge, a landscape of railroad tracks being destroyed, a trek through a swamp and an attack by military school cadets (“Why, those’re nothing but children! They’re school boys!”).

In three of the five films, Wayne’s character has lost his wife, either through death or divorce. Here it’s through medical malpractice, and his telling of her death is one of the dramatic highs in the movie. He’s Colonel Marlowe, leading a raid into Confederate Mississippi, based on the historical campaign of Colonel Benjamin Grierson. Marlowe’s antagonist/buddy (remember The Comancheros?) is Major Kendall (William Holden), a surgeon attached to the unit against Marlowe’s wishes.

Humor is a necessary ingredient in all John Ford films. The greater the bouts of tragedy and pathos, the greater the need for interludes of relaxing, sometimes over-the-top comic relief. As if Ford is relaxing too much, humor abounds during a long dinner scene in which Southern belle Hannah Hunter (Constance Towers) entertains the Union officers whose army has just confiscated her plantation. Hunter’s hilarious misconstruing Marlowe’s pre-war occupation as a “railroad engineer” is perhaps too long to relate here, only to say, “ding-dong, ding-dong,” which Kendall comically quotes at least twice thereafter. More subtle is her extending a platter of fried chicken to Marlowe. Wearing a low-neck dress, she leans forward. “Now, what was your preference—the leg or the breast?” she asks. “I’ve had quite enough of both, thank you,” he replies.

Humor is a necessary ingredient in all John Ford films. The greater the bouts of tragedy and pathos, the greater the need for interludes of relaxing, sometimes over-the-top comic relief. As if Ford is relaxing too much, humor abounds during a long dinner scene in which Southern belle Hannah Hunter (Constance Towers) entertains the Union officers whose army has just confiscated her plantation. Hunter’s hilarious misconstruing Marlowe’s pre-war occupation as a “railroad engineer” is perhaps too long to relate here, only to say, “ding-dong, ding-dong,” which Kendall comically quotes at least twice thereafter. More subtle is her extending a platter of fried chicken to Marlowe. Wearing a low-neck dress, she leans forward. “Now, what was your preference—the leg or the breast?” she asks. “I’ve had quite enough of both, thank you,” he replies.

Music is by second-stringer David Buttolph, who uses Civil War tunes, including “Lorena,” surely at the request of Ford, who preferred scores with atmospheric, nostalgic music. The prime example is his Stagecoach (1939), which won a Best Score Oscar for its borrowed tunes, in deference that year to more deserving scores, among them Erich Korngold’s Elizabeth and Essex and Alfred Newman’s Wuthering Heights. The main tune, “I Left My Love,” is, however, original—and most appropriate for supporting shots of Union cavalry. It was written by Stan Jones, who also plays General U.S. Grant in the opening scene.

William Clothier, one of the best with Westerns, is the cinematographer—in fact, photographs four of the five films. The movie marked the single film appearance of tennis player Althea Gibson as Hunter’s maid, negating, it would seem, some of the progress she had made in breaking the color barrier in her sport. Because of the death of stuntman Fred Kennedy during filming, it is said that Ford lost interest in the movie, which possibly explains the somewhat abrupt ending.

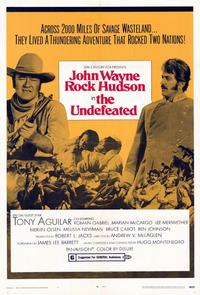

After The Horse Soldiers, you might wonder why The Undefeated (1969) is included here, so extreme is the contrast between the two. The Undefeated makes suspect the criteria set forth at the beginning. Having reviewed the film once again for these musings, I found parts of it—well, sappy, mainly the love interest between Melissa Newman—a terrible actress, delivering her lines with double doses of cow-eyed saccharine—and Roman Gabriel, one of two famous footballers of the day who appear in the film (the other being Merlin Olsen). What form of coercion was used in pushing these men before the camera has not yet been revealed.

After The Horse Soldiers, you might wonder why The Undefeated (1969) is included here, so extreme is the contrast between the two. The Undefeated makes suspect the criteria set forth at the beginning. Having reviewed the film once again for these musings, I found parts of it—well, sappy, mainly the love interest between Melissa Newman—a terrible actress, delivering her lines with double doses of cow-eyed saccharine—and Roman Gabriel, one of two famous footballers of the day who appear in the film (the other being Merlin Olsen). What form of coercion was used in pushing these men before the camera has not yet been revealed.

The redeeming qualities, then, that justify the film’s inclusion?— Foremost is the rapport between ex-Union colonel John Henry Thomas (Wayne) and ex-Confederate colonel James Langdon (Rock Hudson). Despite the recent end of the Civil War, they develop an instant camaraderie. The actors apparently enjoyed each other’s company off camera, for it transfers pleasantly to the screen. Besides, I like “buddy” movies, that warm-all-over feeling derived from people coming together for a common good. And you do get used to Hudson’s Southern accent.

This, after all, is a fun movie, directed by Andrew V. McLaglen, who will also direct the next film. His direction has something of the Ford touch without Ford’s elusive style or cinematic eye.

There’s always, if you look hard enough, a standout performance. Wayne is Wayne here, as he is in four of the films, but not the last. Hudson exists on his relaxed, admittedly likable personality; one almost expects Doris Day to appear from around a boulder, freshly attired in off-the-rack pioneer clothes. No, the outstanding performance is Antonio Aguilar’s as Juárista general Rojas, who wants the horses Thomas and his men have driven across country. Trouble is, Rojas has captured Langdon and his men by a ruse and demands the horses or else. Will Thomas sacrifice the cattle, and all the money he would have gotten for them at market, for the life of his new-found friend? Hum-m-m-m——

There’s always, if you look hard enough, a standout performance. Wayne is Wayne here, as he is in four of the films, but not the last. Hudson exists on his relaxed, admittedly likable personality; one almost expects Doris Day to appear from around a boulder, freshly attired in off-the-rack pioneer clothes. No, the outstanding performance is Antonio Aguilar’s as Juárista general Rojas, who wants the horses Thomas and his men have driven across country. Trouble is, Rojas has captured Langdon and his men by a ruse and demands the horses or else. Will Thomas sacrifice the cattle, and all the money he would have gotten for them at market, for the life of his new-found friend? Hum-m-m-m——

The score is a poor imitation of Elmer Bernstein, though Hugo Montenegro tries.

The knock-down, drag-out fight which occupies practically a centerpiece in The Undefeated—I said this is a “fun movie”—is reprised, complete with mud slide, in the fourth of the five, McLintock (1963). Maybe because the director is also McLaglen. This is the joker I mentioned earlier.

McLintock is pure comedy, a time for “the boys” to relax, with some of John Wayne’s favorite supporting actors, including drinking buddy Bruce Cabot, who appears in three of the five films. Wayne, now as G. W. McLintock, is reunited with one of his favorite leading ladies, Maureen O’Hara, who shared billing with him in, perhaps more famously, The Quiet Man and Rio Grande, though they also made The Wings of Eagles and Big Jake. Here, as in Rio Grande, she plays a wife too prim and proper for her own good—and, as far as McLintock is concerned, for his own good as well.

McLintock is pure comedy, a time for “the boys” to relax, with some of John Wayne’s favorite supporting actors, including drinking buddy Bruce Cabot, who appears in three of the five films. Wayne, now as G. W. McLintock, is reunited with one of his favorite leading ladies, Maureen O’Hara, who shared billing with him in, perhaps more famously, The Quiet Man and Rio Grande, though they also made The Wings of Eagles and Big Jake. Here, as in Rio Grande, she plays a wife too prim and proper for her own good—and, as far as McLintock is concerned, for his own good as well.

The conflict is two-fold. First, the housekeeper (a bewitching Yvonne De Carlo, even at forty-one) McLintock hires seems a threat to Katherine (O’Hara), even though the wife has only returned home to obtain a divorce. Second, their daughter Becky (Stephanie Powers) is to marry a dolt (Jerry Van Dyke), but the housekeeper’s son Devlin (Pat Wayne) pursues her and changes her mind. (Pat Wayne, one of Wayne’s sons, appears in three of the five films.)

In the end, to continue a generally anti-feminist theme, Wayne chases O’Hara through town in her petticoat and ends up spanking her! If this doesn’t convey a sense of the film’s tone, then the meaning of Wayne’s hat on the weather vane might: he throws it there when he’s been out on the town and gotten drunk! And, now, if you haven’t seen the film, maybe you can predict the end. Divorce or no divorce—which do you think?

In the end, to continue a generally anti-feminist theme, Wayne chases O’Hara through town in her petticoat and ends up spanking her! If this doesn’t convey a sense of the film’s tone, then the meaning of Wayne’s hat on the weather vane might: he throws it there when he’s been out on the town and gotten drunk! And, now, if you haven’t seen the film, maybe you can predict the end. Divorce or no divorce—which do you think?

The score is by another second-stringer, Frank De Vol. Westerns, for some reason, are less fortunate than swashbucklers and biblical epics, which usually have better scores. “By” Dunham wrote lyrics and music for most of the songs, rollicking tunes in the manner of The Cheyenne Social Club and ¡Three Amigos!, by other composers. The songs will be forgotten by the end of the final credits.

The only one of these films not photographed by William Clothier—wholly unintentional, I assure you—was shot by William C. Hoch, who won an Oscar for She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. But, ah-ha!, Ribbon is not the fifth film—a better one is, perhaps John Ford’s Western masterpiece.

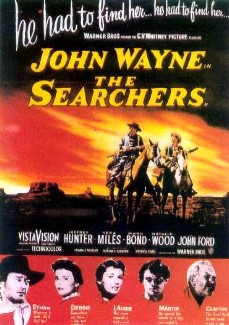

Unappreciated by critics of the time, though now hard to understand, The Searchers (1956) has that sweep I mentioned before, only here far beyond any of the other films.

At the same time, though the initial impression is of outdoor expanses, there is the much stronger impact of an ex-Confederate soldier’s inner torment, his racism, his loneliness. Wayne considered the role of Ethan Edwards his favorite and best—and it’s easy to see why. Any number of close-ups reveal the concentrated hatred in his eyes, the knowledge of what he has to do regarding the capture of his niece Debbie by Indians—early on, looking across the saddle of his horse and, later, when he sees first hand white children who have been prisoners of the Indians. (Debbie is played by Lana Wood as a child and by Natalie Wood as a young woman.)

It would seem that, in life, Wayne had endured some searing tragedy which, recalling, he could pull from deep inside and replicate. James Stewart, having seen inhumanity and death during World War II, was able to produce the wide-eyed terror so harrowing in It’s a Wonderful Life, his first film after the war. But Wayne refused to enlist, so what we see in his eyes, from the perspective of any known personal experience, is inexplicable.

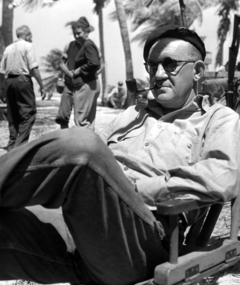

Before Ford proclaimed Wayne the best actor in Hollywood, he had said, after seeing him in director Howard Hawks’ Red River, “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act.” Surely, for Ford it was tongue in cheek. As a man who disavowed sentimentality, it was a guarded compliment, and as a first-class director, he must have known, all along, that Wayne was a good actor.

About the music—— Earlier, in discussing The Comancheros, I implied the possible superiority of the score for that great film to come. In The Searchers, Max Steiner is somewhat unSteinerish, restraining that proclivity for quoting any number of ready-made tunes, traditional, folk, what-have-you, and here providing subtle music that supports the screen without exaggeration. There are a few concessions to cavalry tunes, the Civil War “Lorena” and Ford’s favorite hymn, “Shall We Gather at the River,” traditional for his film funerals, as here, and the “Indian music” recalls the Indian motif from Steiner’s They Died With Their Boots On. The vocals by the Sons of the Pioneers, beginning immediately behind the opening credits, hint at the tragic nature of “a man,” the Ethan Edwards we will soon meet. The singing group was a stalwart of many a Ford Western.

It’s been said that The Searchers is the film of a disillusioned director. Ford, more than anything, loved the western landscape, especially Monument Valley where this and many of his Westerns were filmed. He, too, had experienced WWII, relishing his part as a photographer, and the war had changed him as well. Perhaps, too, he was unhappy with the transformations he saw in the country after his return home.

It’s been said that The Searchers is the film of a disillusioned director. Ford, more than anything, loved the western landscape, especially Monument Valley where this and many of his Westerns were filmed. He, too, had experienced WWII, relishing his part as a photographer, and the war had changed him as well. Perhaps, too, he was unhappy with the transformations he saw in the country after his return home.

And, too, his view of the American Indian had changed. Although he had pictured them more fairly and humanely than most directors, by the time of The Searchers he realized, which was always a glaring truth, that the white man was equally guilty of injustice and murder. He emphasizes this in the annihilation of an Indian village by the U. S. Cavalry. Later, in his final Western, Cheyenne Autumn, he graphically depicts the cruel displacement of the Indians.

In the darkest scene in any of Ford’s movies, the massacre of the prairie family, which Edwards had visited in the opening of the film, is so horrific that he prevents Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter) from witnessing it. Likewise, when Edwards later finds the violated body of one of the two girls from the attacked household, nothing graphic is shown. The horror is revealed in Edwards’ body language and in his words: “Whatya want me to do—draw ya a picture, spell it out? Don’t ever ask me. Long as you live, don’t ever ask me more!”

The Searchers is about a quest—not about the group which originally set out, nor even about the two men who continue, but about Edwards’ solitary, inner search, whether physically alone or not, for Debbie. And when he finds her, as is apparent throughout the movie, without his ever having to say so, he plans to kill her. Because she lived with the Indians, he feels she isn’t fit to live, so deep is his racism.

But Ford draws back from what seemed a foregone eventuality—and we still believe he will kill her, right up to the moment he tracks her down near a cave. Instead, Edwards picks her up, dressed in her Indian clothes, and says, “Let’s go home, Debbie.” After this hate has been reinforced, time and again through the darkest scenes—remember those eyes?!—it is a rather unrealistic turnabout. Perhaps it would be too much of a downer if Ford had carried through, making the film ultimately negative.

But Ford draws back from what seemed a foregone eventuality—and we still believe he will kill her, right up to the moment he tracks her down near a cave. Instead, Edwards picks her up, dressed in her Indian clothes, and says, “Let’s go home, Debbie.” After this hate has been reinforced, time and again through the darkest scenes—remember those eyes?!—it is a rather unrealistic turnabout. Perhaps it would be too much of a downer if Ford had carried through, making the film ultimately negative.

But the loneliness for Edwards is still there, and, presumably, the hate, too. After Debbie’s restoration to her family, and after all members have entered the house, Edwards stands alone, outside. He turns and wanders away, alone, as he had arrived. And the opening shot of the film, from inside a house, becomes the final shot, only now the door, instead of opening, is closing.

It is one of the great endings in film history, in this, the greatest Western in film history.