“If more women were invisible, life would be much less complicated.”— Professor Gibbs

“If more women were invisible, life would be much less complicated.”— Professor Gibbs

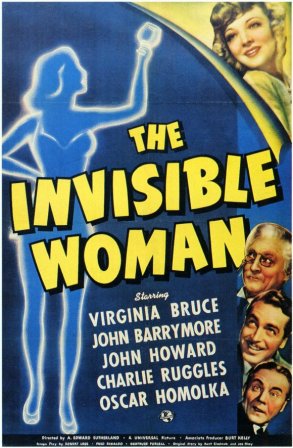

The 1940 Universal movie The Invisible Womanis an obvious sequel of sorts to The Invisible Man, made seven years earlier by the same studio, and starring the great Claude Rains, who almost single-handed carries the film. Manhas its comic moments, but it also has its dark side and tragic consequences for Jack Griffin, Rains’ character, who achieves invisibility but is unable to “get back,” and is driven insane, shot in the snow by the police and dies in the hospital, only then becoming visible for the first time in the movie.

The Invisible Woman has no such serious moments, isn’t a horror film and exists purely for laughs and lively slapstick, though the presence of John Barrymore may pique the curiosity. Whatever happened to him, anyway, this member of the famous Barrymore dynasty, this actor once called the greatest Hamlet of all time? Although his fall from grace was caused by alcoholism and fading memory, in Woman he seems to hold up his end fairly well, wandering through the film with a subtle comic flair, which he never lost, even, it’s rumored, on his deathbed. This was Barrymore’s third-to-last film. He would die in 1942.

The special effects, which were such a novelty in The Invisible Man and are a bit less sophisticated and inventive in the female counterpart, are the central attraction of both films, the work of special effects wizard John P. Fulton. He also helped bring to life, as it were, some of Universal’s trademark horror films—Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Mummy, Werewolf of London,The Wolf Man and many other titles.

The director is the little-known A. Edward Sutherland, one of the original Keystone Kops and director of a number of W. C. Fields and Laurel and Hardy comedies. If nothing else, he keeps the pace hopping. Better known is Elwood Bredell, the film’s cinematographer, responsible for Hellzapoppin’, Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, Adventures of Don Juan and The Inspector General. He may not be one of the great cinematographers by any means, but he proves again that even the minor artists of Hollywood’s golden age could turn in the goods.

Despite the two films being from the same studio, and not all that many years apart, there are few carryovers among the supporting players. Henry Travers, John Carradine, Holmes Herbert, Una O’Connor, Dwight Frye, Forrester Harvey, even the redoubtable E. E. Clive—all in Man—are absent in Woman. However, Mary Gordon, landlady to Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes in that same studio’s detective series, does appear in both films, if nothing more than “appear.”

Despite the two films being from the same studio, and not all that many years apart, there are few carryovers among the supporting players. Henry Travers, John Carradine, Holmes Herbert, Una O’Connor, Dwight Frye, Forrester Harvey, even the redoubtable E. E. Clive—all in Man—are absent in Woman. However, Mary Gordon, landlady to Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes in that same studio’s detective series, does appear in both films, if nothing more than “appear.”

Still, there are enough familiar names in the supporting cast of The Invisible Woman to be a treat for anyone looking for those old familiar faces that made the films of the ’30s and ’40s such adventures in a kind of can-you-pick-them-out game. The supporting casts in both films, nonetheless, are of the same generation.

Receiving top billing, even above Barrymore, Virginia Bruce replaced Margaret Sullavan, who thought The Invisible Woman beneath her acting skills. For some reason, I often confuse Bruce with Virginia Grey, maybe, not that they look anyway alike (they don’t), but because both are “B” leading ladies, often play “the other woman” and, yes, both display similar personae, with limited charisma.

Receiving top billing, even above Barrymore, Virginia Bruce replaced Margaret Sullavan, who thought The Invisible Woman beneath her acting skills. For some reason, I often confuse Bruce with Virginia Grey, maybe, not that they look anyway alike (they don’t), but because both are “B” leading ladies, often play “the other woman” and, yes, both display similar personae, with limited charisma.

Bruce here is very much up front in the action, playing Kitty Carroll, who answers daffy Professor Gibbs’ (Barrymore) newspaper ad for a volunteer, someone who wishes to become invisible—and attain all the questionable advantages that provides. A department store model, Kitty sees possibilities in such a transformation, a way of getting even with her mean-spirited boss, appropriately named Mr. Growly (Charles Lane), who has fired her for being honest with her customers when a sleeve tears during a dress modeling.

In the film’s beginning, lawyer Hudson (Thurston Hall, here in a larger role than usual, but still his blustery self), arrives at the home of playboy Richard Russell (John Howard, fresh from The Philadelphia Story). Hudson is greeted at the door by George the butler (Charles Ruggles, the eccentric leopard-caller in Bringing Up Baby and famously teamed with Mary Boland in a comedy series in the early ’30s). George, already, has done a pratfall down a staircase, sending a serving tray flying, and, moments later, has another encounter with the floor at the front door.

“Get up! Get up!” Hudson tells him. “I am up,” George replies. “I was up. And I’ve been up all night. I would have stayed up if you hadn’t knocked me down.”

Hudson tells Russell that because of his extravagant living, he’s flat broke, which means there won’t be any more money for Gibbs’ work on his invisibility machine. His home/laboratory is in an outbuilding on the Russell estate, complete with housekeeper Mrs. Jackson (Margaret Hamilton in an undernourished part), who sometimes does the eccentric old fossil’s bidding, and at others—well, Hamilton has always been rather arrogantly independent.

Hudson tells Russell that because of his extravagant living, he’s flat broke, which means there won’t be any more money for Gibbs’ work on his invisibility machine. His home/laboratory is in an outbuilding on the Russell estate, complete with housekeeper Mrs. Jackson (Margaret Hamilton in an undernourished part), who sometimes does the eccentric old fossil’s bidding, and at others—well, Hamilton has always been rather arrogantly independent.

Kitty answered Gibbs’ newspaper ad using a man’s name, so the professor is surprised, to say the least, when a woman appears at his doorstep. He’s game though and quickly asks her to undress for the first test for his machine. The machine works! (Amazing, even in this comedy the Hollywood censors were concerned about “nudity” on screen!) When Kitty later has to dress, now invisible, she complains, “This is worse than dressing in the dark.”

Russell and Kitty have a love-hate relationship, with little time to concentrate on either feeling. Their scenes are incidental to the special effects—clothes moving without bodies, floating objects, unseen slaps—and then the second half of the film begins with a visit by gangdoms very own. Gangster Foghorn (Donald MacBride) arrives with his two henchmen, Bill (gangster specialist Edward Brophy, from The Thin Man to The Last Hurrah) and Frankie (Shemp Howard, one of the original Three Stooges). They’ve come to steal the professor’s machine. The gang coerces the old fuddy-duddy into demonstrating it, to see if it will work on their boss “Blackie” Cole (Oscar Homolka, an Austrian adept at both comedy and drama), who wants to return to Russia—really incognito.

Russell and Kitty have a love-hate relationship, with little time to concentrate on either feeling. Their scenes are incidental to the special effects—clothes moving without bodies, floating objects, unseen slaps—and then the second half of the film begins with a visit by gangdoms very own. Gangster Foghorn (Donald MacBride) arrives with his two henchmen, Bill (gangster specialist Edward Brophy, from The Thin Man to The Last Hurrah) and Frankie (Shemp Howard, one of the original Three Stooges). They’ve come to steal the professor’s machine. The gang coerces the old fuddy-duddy into demonstrating it, to see if it will work on their boss “Blackie” Cole (Oscar Homolka, an Austrian adept at both comedy and drama), who wants to return to Russia—really incognito.

The antics that follow would do credit—if that’s an appropriate comparison—to the Three Stooges, and not merely because of Shemp Howard’s presence. The gangsters cavort with the machine, which has its side effects. Foghorn acquires a falsetto voice after passing through the device, and as George, who clearly has the best lines, says, “I don’t know [who’s at the door], sir, but it sounds like Jenny Lind.”

Kitty, once she has become seeable again, learns that alcohol will return her to invisibility. Being unseen is needed to defeat the gangsters, who have stolen the machine and taken it to their hideout in Mexico. Further, this invisibility thing seems to be hereditary; after Kitty and Russell are married and have a child, the infant becomes invisible when rubbed with an alcohol-based cream. Of course, John P. Fulton’s best special effects moment, now combined with Lane’s convincing startled disbelief, is Kitty’s final appearance at the department store. At a fashion show—a gown without a head—she sends the ladies running for their lives. In Growly’s office, Kitty first appears without a head and proceeds to remove her clothes until there’s nothing left but her gloves, in the invisible buff, which also managed to pass those censors! She yanks Growly by his tie, bangs the window pane on his head and kicks him in the derriere (discreetly implied in a view from outside the window). Even the gloves gone now, Kitty slams Growly’s office door, the glass panes shattering to the floor. Chairs, a water cooler, a time clock, seemingly on their own, crash to the floor on her exit. With one final goggle-eyed stare, Growly faints backward to the floor.

Of course, John P. Fulton’s best special effects moment, now combined with Lane’s convincing startled disbelief, is Kitty’s final appearance at the department store. At a fashion show—a gown without a head—she sends the ladies running for their lives. In Growly’s office, Kitty first appears without a head and proceeds to remove her clothes until there’s nothing left but her gloves, in the invisible buff, which also managed to pass those censors! She yanks Growly by his tie, bangs the window pane on his head and kicks him in the derriere (discreetly implied in a view from outside the window). Even the gloves gone now, Kitty slams Growly’s office door, the glass panes shattering to the floor. Chairs, a water cooler, a time clock, seemingly on their own, crash to the floor on her exit. With one final goggle-eyed stare, Growly faints backward to the floor.

John Barrymore, known as the Great Profile, made his best talkies in the early thirties, before his drinking interfered with his work: A Bill of Divorcement, which brought Katharine Hepburn to the movies,Twentieth Century, Grand Hotel and Dinner at Eight. Or maybe, more accurately, these were the best of his films in which he appeared, as the latter two were true ensemble pictures, shared with numerous other stars—Great Garbo, Joan Crawford, Wallace Beery, Jean Harlow, Marie Dressler and brother Lionel Barrymore.

Beginning in 1912 with the silents and continuing into the early talkies, Barrymore played a variety of familiar characters—Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Sherlock Holmes, Don Juan, Richard III and Hamlet, Svengali and Ahab in Moby Dick (1930)—all to be later played by others. In the same year as The Invisible Woman, he made a more or less parody of himself, The Great Profile, about a drunken actor. By this time, Barrymore was reading his lines from blackboards, which, surprisingly, he did with aplomb, to no detriment to the film’s schedule.

Beginning in 1912 with the silents and continuing into the early talkies, Barrymore played a variety of familiar characters—Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Sherlock Holmes, Don Juan, Richard III and Hamlet, Svengali and Ahab in Moby Dick (1930)—all to be later played by others. In the same year as The Invisible Woman, he made a more or less parody of himself, The Great Profile, about a drunken actor. By this time, Barrymore was reading his lines from blackboards, which, surprisingly, he did with aplomb, to no detriment to the film’s schedule.

Many of the best and most typical comments by this lecherous predator of young and old actresses alike are too racy to quote here, but here are a few of his tamer observations on life and acting: “The good die young, because they see no point in living if you have to be good.” When asked during his final illness about dying, he replied, “Die? I should say not, old fellow. No Barrymore would allow such a conventional thing to happen to him.” He was once asked by a student of Shakespeare, “Tell me, Mr. Barrymore, in your view, did Ophelia ever sleep with Hamlet?” After some thought, the actor replied, “Only in the Chicago company.”

It isn’t surprising that Virginia Bruce’s nemesis in The Invisible Woman, Charles Lane, appeared in a number of Barrymore films, including Twentieth Century and The Great Profile. He made literally hundreds of films, and would be the clear winner in any of those can-you-pick-them-out games, even more frequent in screen appearances than those much-seen supporting actors Harry Davenport, Henry Stephenson and Edward Everett Horton.

It isn’t surprising that Virginia Bruce’s nemesis in The Invisible Woman, Charles Lane, appeared in a number of Barrymore films, including Twentieth Century and The Great Profile. He made literally hundreds of films, and would be the clear winner in any of those can-you-pick-them-out games, even more frequent in screen appearances than those much-seen supporting actors Harry Davenport, Henry Stephenson and Edward Everett Horton.

As one of the last survivors of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 and among the first performers to join movie and television guilds, Lane wasn’t in real life the miserly, odious bureaucrat with the permanent scowl he presented in most of his films. Actually a nice man, he was a mainstay in many of Frank Capra’s films, including Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, You Can’t Take It with You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and It’s a Wonderful Life. His other films include the original Blondie, The Cat and the Canary (1939), Ball of Fire, The Farmer’s Daughter, Call Northside 777, Teacher’s Pet, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and Murphy’s Romance.

Going into TV in the early ’50s, and for over four decades, he became everywhere on the tube—in I Love Lucy, Perry Mason, The Twilight Zone, St. Elsewhere, L.A. Law and so many others. He is best remembered, perhaps, as the cantankerous—what else?—railroad executive Homer Bedloe in TV’s Petticoat Junction.

Going into TV in the early ’50s, and for over four decades, he became everywhere on the tube—in I Love Lucy, Perry Mason, The Twilight Zone, St. Elsewhere, L.A. Law and so many others. He is best remembered, perhaps, as the cantankerous—what else?—railroad executive Homer Bedloe in TV’s Petticoat Junction.

In 2006, Lane narrated a Night Before Christmas short and just before his death was working on a documentary, You Know the Face, detailing his long career. He lived to be 102, dying in 2007, active almost to the end.