“We knew that poor Oates was walking to his death, but though we tried to dissuade him, we knew it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman. We all hope to meet the end with a similar spirit and assuredly the end is not far.” —— Robert Falcon Scott

“We knew that poor Oates was walking to his death, but though we tried to dissuade him, we knew it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman. We all hope to meet the end with a similar spirit and assuredly the end is not far.” —— Robert Falcon Scott

If ever there was a more apt movie about stiff upper lip British stalwartness, aside from those films recounting the foolish “over-the-top” courage in the trenches of World War I, the story of Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-fated 1911-1912 expedition to Antarctica, as meticulously detailed in Scott of the Antarctic (1948), would be an excellent example. The film is further complemented by an equally stalwart performance by John Mills as the title character.

This stalwartness, though, came at a price and, as some would later say and write, with harsh criticism about Scott’s handling of his expedition.

Although cartographers as early as the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had shown some kind of land really “down under” without any certainty there was such a place, a U.S. sea captain, Nathaniel Palmer, was believed to be the first, in 1820, to sight the mainland of Antarctica, part of a peninsula that reaches further north than any other part of that continent, to within six hundred miles of Chile’s southern tip.

As a commander in the Royal Navy, Falcon Scott had made his first trek to Antarctica—the Discovery Expedition—in 1901-1904. Then he studied the weather and the earth’s magnetism, becoming the first Antarctic explorer to venture out from a land base with previously laid down stores, a practice adopted by others. Accompanying Scott on this enterprise was Irishman Ernest Shackleton, who later returned to Antarctica with his own party in 1908.

As a commander in the Royal Navy, Falcon Scott had made his first trek to Antarctica—the Discovery Expedition—in 1901-1904. Then he studied the weather and the earth’s magnetism, becoming the first Antarctic explorer to venture out from a land base with previously laid down stores, a practice adopted by others. Accompanying Scott on this enterprise was Irishman Ernest Shackleton, who later returned to Antarctica with his own party in 1908.

It was Norwegian Roald Amundsen, however, whom Scott should have worried about, for at the time of Scott’s next trek in 1911, the Terra Nova Expedition, Amundsen headed out on his own and beat the Englishman to the South Pole by a little over a month, becoming the first human being to reach the southern end of the earth’s axis. Arriving at the Pole on January 18, 1912, Scott and his five-man team found Amundsen’s tent, the Norwegian flag, a letter addressed to the King of Norway and the names of the five explorers. Scott and his four companions died on their return journey.

Scott’s expedition was, in fact, an out-and-out tragedy, due, to a considerable degree, to Scott himself—even beyond worse weather than expected and an uncontrollable chain of bad luck. There was what was called at the time his “Pole mania,” his independent planning without advice from others, his desire “to secure for the British Empire the honour of this achievement” (before it was achieved) and his general obstinacy and over confidence. “I feel sure,” he wrote at one point, “we are as near perfection as experience can direct.”

Amundsen had relied mainly on horses and a large number of dogs, both with success. Scott’s broader strategy was to include dogs as well as ponies and motor sledges for hauling food and supplies. The tractors, which he tested in the spring, froze up in the arctic cold. The ponies, purchased in Manchuria by someone, selected by Scott, who knew nothing about such animals, were of poor quality and slowed the men’s pace. They either died from the cold or had to be shot.

Amundsen had relied mainly on horses and a large number of dogs, both with success. Scott’s broader strategy was to include dogs as well as ponies and motor sledges for hauling food and supplies. The tractors, which he tested in the spring, froze up in the arctic cold. The ponies, purchased in Manchuria by someone, selected by Scott, who knew nothing about such animals, were of poor quality and slowed the men’s pace. They either died from the cold or had to be shot.

For fifty years after his death, Robert Falcon Scott was regarded in Great Britain as a hero, given a memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral and honored throughout Britain with countless statues and stained glass windows. Remnants of his expedition were enshrined in churches, much as in the Middle Ages when the hearts and other body parts of supposed saints were preserved and worshipped in reliquaries.

Only in the last of the twentieth century was the true nature of Scott’s expedition reassessed and viewed in a more rational light. In countless books, new criticisms poured forth. In 1977, David Thomson called Scott not a great man, “at least not until near the end.” Roland Huntford, a few years later, called the explorer an “heroic bungler.” More recently, Francis Spufford wrote, “Scott doomed his companions, then covered his tracks with rhetoric.” Indeed, if his surviving journal is a record of meticulous planning, it is also an inspiring piece of literature, an account of devoted companionship and incredible courage.

Only in the last of the twentieth century was the true nature of Scott’s expedition reassessed and viewed in a more rational light. In countless books, new criticisms poured forth. In 1977, David Thomson called Scott not a great man, “at least not until near the end.” Roland Huntford, a few years later, called the explorer an “heroic bungler.” More recently, Francis Spufford wrote, “Scott doomed his companions, then covered his tracks with rhetoric.” Indeed, if his surviving journal is a record of meticulous planning, it is also an inspiring piece of literature, an account of devoted companionship and incredible courage.

Enough history. It remains only to say that most of the character names used in the film, and all those mentioned in this article, are those of the real participants in the fateful adventure.

The self-assured Scott (Mills) is evident from the very opening of the film when he announces to his wife (Diana Churchill, not the daughter of Sir Winston) that he is returning to Antarctica on a second expedition. As she fashions a bust of her husband, she says she is “not the least jealous.” The wife (Anne Firth) of the first man Scott asks to join his endeavor is less enthusiastic. Her husband Edward Wilson (Harold Warrender, Locksley in Ivanhoe, Geoffrey Fielding in Pandora and the Flying Dutchman), who had been on Scott’s first expedition, agrees to go.

Unlike his first expedition, Scott this time has no government financing; he sets about with campaigns and speeches to raise money and, of course, supposedly selects the heartiest and most experienced men to accompany him. At least in the film, he seems rather cavalier in his selection, impressed simply because one man had come from India to join up, another because he has hefty biceps.

The three men highlighted at this point in the film are the ones who will accompany Scott and Wilson on the final sprint for the Pole. “Taff” Evans is played by James Robertson Justice, who wanted to do the movie so badly he shaved his beard; he appears in many adventure films: The Black Rose, Above the Waves, Moby Dick. Henry Bowers is played by Reginald Beckwith, Kenniston in Thunderball and the phony medium in Curse of the Demon. Last of the three, Lawrence (“Titus”) Oates is played by Derek Bond, the title character in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, made by the same English studio, Ealing, which made Scott of the Antarctic.

The three men highlighted at this point in the film are the ones who will accompany Scott and Wilson on the final sprint for the Pole. “Taff” Evans is played by James Robertson Justice, who wanted to do the movie so badly he shaved his beard; he appears in many adventure films: The Black Rose, Above the Waves, Moby Dick. Henry Bowers is played by Reginald Beckwith, Kenniston in Thunderball and the phony medium in Curse of the Demon. Last of the three, Lawrence (“Titus”) Oates is played by Derek Bond, the title character in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, made by the same English studio, Ealing, which made Scott of the Antarctic.

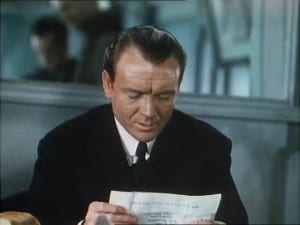

Before the ship departs for Antarctica, Scott receives a telegram and stuffs it in his pocket. Later, while under sail, he reads the message. Roald Amundsen, it appears, has himself departed for Antarctica by a route other than the one he first announced. “Why did he suddenly change his mind?” Scott asks. “I’m not going to make it a race.” After a pause: “Wonder what route the blighter’s taking?”

During the six months of winter spent at his base camp before heading in earnest for the South Pole—all the while his men venturing out to establish food and supply depots for the return trek—Scott receives word that Amundsen, with more than a hundred dogs, is at the Bay of Whales, about two hundred miles west of him, on the northern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf.

During this long Polar Night, Scott, even now writing in his journal, is entertained by men clowning around as Russian dancers, listening to the gramophone (Clara Butt’s 1910 recording of “Abide With Me”) and enjoying a recitation, “The Sleeping Bag,” by Scott’s photographer Herbert Pointing (Clive Morton, the prison governor in Kind Hearts and Coronets). The poem begins:

During this long Polar Night, Scott, even now writing in his journal, is entertained by men clowning around as Russian dancers, listening to the gramophone (Clara Butt’s 1910 recording of “Abide With Me”) and enjoying a recitation, “The Sleeping Bag,” by Scott’s photographer Herbert Pointing (Clive Morton, the prison governor in Kind Hearts and Coronets). The poem begins:

“On the outside grows the fur side. On the inside grows the skin side. So the fur side is the outside and the skin side is the inside. One side likes the skin side inside and the fur side on the outside. Others like the skin side outside and the fur side on the inside. If you turn the skin side outside, thinking you will side with that side, then the soft side, fur side’s inside, which some argue, is the wrong side. . . . ”

When the arctic winter is over, Scott sets out with sixteen men, ponies, dogs, tractors and four supply sledges, which contain food, tents, fuel for their cooking stoves and supplies. They must traverse three obstacles: the Ross Ice Shelf, the Beardmore Glacier and the flat, featureless Polar Plateau, in the center of which is their objective.

When the arctic winter is over, Scott sets out with sixteen men, ponies, dogs, tractors and four supply sledges, which contain food, tents, fuel for their cooking stoves and supplies. They must traverse three obstacles: the Ross Ice Shelf, the Beardmore Glacier and the flat, featureless Polar Plateau, in the center of which is their objective.

Since first arriving in Antarctica, as if the nuisance of Amundsen isn’t enough of an omen, their ship, “Terra Nova,” had been caught in pack ice for twenty days and a motor sledge had fallen into the sea while being unloaded from the ship. Now the remaining motor sledges freeze up in the cold and the ponies, no better acclimatized, have to be shot.

At planned points along the journey, one at a time, the three sets of four men, now man hauling their sledges, head back to the base camp. The dogs had returned with the first group. With the glacier behind them and only two sets of four men remaining, including Scott’s own team, it is time for the last set to turn back. From the seven men who remain, Scott selects with great care those who will accompany him to the Pole—the healthiest and most able to withstand the cold. He decides, against his original plan, to take an extra man, one from the returning four, so his companions will be Wilson, Bowers, Evans and Oates.

At planned points along the journey, one at a time, the three sets of four men, now man hauling their sledges, head back to the base camp. The dogs had returned with the first group. With the glacier behind them and only two sets of four men remaining, including Scott’s own team, it is time for the last set to turn back. From the seven men who remain, Scott selects with great care those who will accompany him to the Pole—the healthiest and most able to withstand the cold. He decides, against his original plan, to take an extra man, one from the returning four, so his companions will be Wilson, Bowers, Evans and Oates.

Immediately, Scott finds that “cooking for five takes considerably more time than cooking for four.” When they arrive at the South Pole—there is no music at this point, only the wind—the party finds that Amundsen has beaten them. “Great God, this is an awful place!” Scott says. Using a long string rigged to the shutter switch, they take their picture, three standing, two sitting, in front of their Union Jack. Then they begin the trek back.

“The Norwegians have forestalled us and are first at the Pole,” Scott writes in his journal. “It is a terrible disappointment and I am very sorry for my loyal companions. Many thoughts come and much discussion we have had. Tomorrow we must . . . hasten home with all the speed we can compass. All the day-dreams must go; it will be a wearisome return.”

“The Norwegians have forestalled us and are first at the Pole,” Scott writes in his journal. “It is a terrible disappointment and I am very sorry for my loyal companions. Many thoughts come and much discussion we have had. Tomorrow we must . . . hasten home with all the speed we can compass. All the day-dreams must go; it will be a wearisome return.”

After making good progress at the beginning of the nine-hundred-mile slog, poor weather becomes more of a problem and Evans, who had concealed a cut finger before Scott made his selections, dies in the snow from exhaustion and frostbite. As the remaining four proceed, they are plagued by unrelenting blizzards, frostbite, hunger and exhaustion. At the last supply depot they are able to reach, they find a half empty fuel canister.

Oates, realizing his weakening condition and frostbitten foot will only slow down the others, leaves the tent, saying, “I am just going outside and may be some time.” He never returns. The men, sharing thoughts and glances, understand. “A brave man and gallant gentleman,” Scott writes. Confined to their tent by an unremitting blizzard, they can make no further progress.

Oates, realizing his weakening condition and frostbitten foot will only slow down the others, leaves the tent, saying, “I am just going outside and may be some time.” He never returns. The men, sharing thoughts and glances, understand. “A brave man and gallant gentleman,” Scott writes. Confined to their tent by an unremitting blizzard, they can make no further progress.

The frozen bodies of the three remaining men, Scott, Wilson and Bowers, were found six months later on the Ross Ice Shelf, only eleven miles from the next depot, called One Ton Depot, where food and supplies would have been plentiful. Scott died March 29, 1912, judging by his last journal entry:

“I do not regret this journey; we took risks, we knew we took them. Things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last. . . . Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. . . . ”

For the most part, the documentary-style film is meticulously accurate and, perhaps at times, some viewers, especially those expecting an adventure film, which Scott of the Antarctic certainly isn’t, may find the detail excessive, even unnecessary. For others, the never-changing white landscape, the frequent slow pans across monotonous terrain, the shots of bundled feet, or feet with skis, plodding through snowdrifts, the moderate use of quick cutting and the almost always slow, dark, minor-key music of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ score might all be too muted and even depressing.

For the most part, the documentary-style film is meticulously accurate and, perhaps at times, some viewers, especially those expecting an adventure film, which Scott of the Antarctic certainly isn’t, may find the detail excessive, even unnecessary. For others, the never-changing white landscape, the frequent slow pans across monotonous terrain, the shots of bundled feet, or feet with skis, plodding through snowdrifts, the moderate use of quick cutting and the almost always slow, dark, minor-key music of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ score might all be too muted and even depressing.

The sound of wind and blizzards, the dull flapping of the tent, the flickering flame of the stove and the almost unrecognizable faces of the huddled inhabitants, bearded, frostbitten and framed by fur caps—all this may well have an accumulative impact, in a different direction. So beware: those same viewers who feel worn down by the methodical, unhurried rhythms of screen and music may be movedby something else, something more, the courage and self-sacrifice of the five men who died attempting to return from the South Pole. The odds they were up against! A test of spirit and fortitude unimaginable to most of us today, so cocooned are we in comfort and leisure.

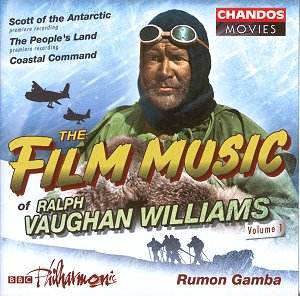

Ralph Vaughan Williams as film composer, vis-à-vis the composer of symphonies and choral works, is perhaps a less familiar name than some of his fellow film-writing Brits—Patrick Doyle (Henry V [1989]), Malcolm Arnold (The Bridge on the River Kwai), William Walton (Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare trilogy) or Ron Goodwin (The Battle of Britain). RVW came late to the genre, scoring his first film, 49th Parallel, in 1941, when he was sixty-nine, and composing mostly for documentaries.

Ralph Vaughan Williams as film composer, vis-à-vis the composer of symphonies and choral works, is perhaps a less familiar name than some of his fellow film-writing Brits—Patrick Doyle (Henry V [1989]), Malcolm Arnold (The Bridge on the River Kwai), William Walton (Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare trilogy) or Ron Goodwin (The Battle of Britain). RVW came late to the genre, scoring his first film, 49th Parallel, in 1941, when he was sixty-nine, and composing mostly for documentaries.

From the first, RVW took to the medium with enthusiasm. For Scott of the Antarctic he put down almost a thousand bars of music, of which less than half were used, before the film was finished. Impressed with what he had written, he later reorganized the material into the Sinfonia Antarctica, his Symphony No. 7. At the head of each of the five movements, he appended quotes from five different authors, including Shelley, King David of the Old Testament, Coleridge, Donne and, for the final movement, which depicts the opposition of man and Nature, part of the quote cited above from Scott’s journal, i.e., “I do not regret this journey . . . ”

As his second wife Ursula wrote: “The idea of great, white landscapes, ice floes, the whales and penguins, bitter winds and Nature’s bleak serenity as a background to man’s endeavour captured RVW’s imagination. He conjured dramatic and icy sounds from the orchestra . . . Here he was following ideas he had explained in an article he had written on composing for the films—‘to ignore details and to intensify the spirit of the whole situation by [a] continuous stream of music.’ ” The already large orchestra is supplemented by xylophone, glockenspiel, an organ, even a wind machine and the ever-present film composers’ friend, the vibraphone.

As his second wife Ursula wrote: “The idea of great, white landscapes, ice floes, the whales and penguins, bitter winds and Nature’s bleak serenity as a background to man’s endeavour captured RVW’s imagination. He conjured dramatic and icy sounds from the orchestra . . . Here he was following ideas he had explained in an article he had written on composing for the films—‘to ignore details and to intensify the spirit of the whole situation by [a] continuous stream of music.’ ” The already large orchestra is supplemented by xylophone, glockenspiel, an organ, even a wind machine and the ever-present film composers’ friend, the vibraphone.

The screen and the music set the mood in the very beginning of the main title—the harsh, frozen landscape of Antarctica reflected in RVW’s austere tone colors, mournful legato strings, with the least possible suggestion of movement, and the loneliness, the isolation, of a single, wordless soprano voice. Later, he uses a wordless female choir to great effect. This unhurried and painfully unrelenting musical mood is generally deliberately sustained for the expedition scenes, or about three-quarters of the film. Exceptions are the lively, playful music for the waddling penguins and the dramatic sighting—on the southward trek—of the glacier, represented by a deep organ pedal.

For those who may be intimidated by the music in its symphony, or “classical,” form, there is the highly recommended Chandos CD of RVW film music, Vol. I, including a forty-minute suite from the film, as long as the symphony itself and featuring music not in the final work. Some of the more contrasting excerpts include those depicting the landscape—“The Ice Floes,” “Snow Plain” and “Climbing the Glacier.” Especially affecting are “Blizzard,” with choir and wind machine, and the poignant “The Deaths of Evans and Oates.” The CD is filled out with much shorter suites from two documentaries, Coastal Command and The People’s Land. Rumon Gamba conducts the BBC Philharmonic.

By the very nature of the film, and its painstaking scientific accuracy, Charles Frend’s direction is unintentionally, even unavoidably slow-paced. Aside from stock footage of Graham Land (the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula), the winter landscapes were filmed in the Swiss Alps. The three cinematographers, like the music and the actors’ performances, deserve a lot of the credit for the success of the film: Jack Cardiff, Osmond Borradaile and Geoffrey Unsworth. Besides Cardiff, whose prowess as a photographer has already been praised in these pages, Unsworth carries his own impressive credits—Becket, Cabaret, Murder on the Orient Express and Tess.

By the very nature of the film, and its painstaking scientific accuracy, Charles Frend’s direction is unintentionally, even unavoidably slow-paced. Aside from stock footage of Graham Land (the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula), the winter landscapes were filmed in the Swiss Alps. The three cinematographers, like the music and the actors’ performances, deserve a lot of the credit for the success of the film: Jack Cardiff, Osmond Borradaile and Geoffrey Unsworth. Besides Cardiff, whose prowess as a photographer has already been praised in these pages, Unsworth carries his own impressive credits—Becket, Cabaret, Murder on the Orient Express and Tess.

After the tent and Scott’s journal were discovered by the rescue team, a white cross overlooking the explorers’ base camp was erected on Observation Hill and inscribed with the names of the five lost men and a line from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Ulysses: “To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”