“I swear there’s something inside.”—— Professor Lindenbrook (the insides of a lump of lava that start the whole journey)

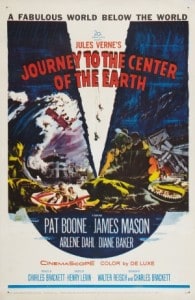

Two other Jules Verne-based movies have been discussed at this site—20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Mysterious Island. From 1959, and filmed between the two, Journey to the Center of the Earth has much to offer, aside from the shortcomings of some cardboard sets. It’s one of those “fun” movies, once called “general audience entertainment,” that they don’t make any more, a rip-roarin’ CinemaScope fantasy-adventure when widescreen was relatively new—and an intended gimmick to lure the growing viewers of Gunsmoke and Father Knows Best away from their TV sets.

[intlink id=”37″ type=”category”]James Mason[/intlink], who took second billing after the then current pop singer Pat Boone and just ahead of Arlene Dahl whose “movie star” treatment annoyed him, was then on the edge of the down slide of his career, having made North by Northwest that same year with Lolita to follow in 1962. Arlene Dahl, whose most significant film had been as long ago as The Bride Goes Wild in 1948 and always felt her talents lay in musical comedy, lent her best attribute, her beauty, but also rendered a respectable performance.

Not the least of the film’s pluses was one of Bernard Herrmann’s best fantasy film scores, with all the trademark “burps” and groans, signs of his love for building-block motifs. The music alone was perhaps the best reason to see—hear?—the movie.

Journey to the Center of the Earth may well be his best effort of the film’s generally middling director, Henry Levin, more famous for a brief string of sex comedies during the late ’50s, early ’60s—April Love, Holiday for Lovers, Where the Boys Are, Come Fly with Me. The wit in the script and the biting repartee are provided by veteran screenwriters Walter Reisch and Charles Brackett. Although the two did collaborate on several occasions during their respective careers, as in Ninotchka and Niagara, their more serious work was in partnership with others, Reisch as a co-writer in That Hamilton Woman and Gaslight, Brackett with Billy Wilder.

Except for the major addition of a requisite love interest, the Journey to the Center of the Earth script has fewer changes in the source material, in this case Verne’s 1864 novel, than is usual in movie makeovers. In the opening scene—changed from Hamburg to Edinburgh—it’s clear that Scotsman Oliver Lindenbrook (Mason) is the typical absent-minded professor. Having purchased a newspaper to read about his recent knighthood, he walks, unawares, into some parading bagpipers. Later, it’s learned that rudeness is also one of his characteristics.

Except for the major addition of a requisite love interest, the Journey to the Center of the Earth script has fewer changes in the source material, in this case Verne’s 1864 novel, than is usual in movie makeovers. In the opening scene—changed from Hamburg to Edinburgh—it’s clear that Scotsman Oliver Lindenbrook (Mason) is the typical absent-minded professor. Having purchased a newspaper to read about his recent knighthood, he walks, unawares, into some parading bagpipers. Later, it’s learned that rudeness is also one of his characteristics.

To celebrate his new honor, his geology students greet him with a song and a present. Among the students is young Alec McKuen (Boone), who presents him with a gift of his own, a lump of lava he saw in a curiosity shop. “A scholar’s choice,” Lindenbrook says. Although McKuen is on an every-other-day diet owing to his poverty, the professor insists he be at his home that evening for dinner.

McKuen has obviously been seeing Lindenbrook’s lovely niece Jenny (Diane Baker) as he complains that she has been ignoring his ardent advances. Before dinner, he expresses his affections with a song at the piano, “My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose,” words by Robert Burns and melody by James Van Heusen—not by Herrmann, who always pointed out that he was not a “pop” composer. It is Boone’s vocal highlight of the film, although two other Van Heusen songs were cut from the final print; Boone does later manage a few lines from “My Heart’s in the Highlands.”

McKuen has obviously been seeing Lindenbrook’s lovely niece Jenny (Diane Baker) as he complains that she has been ignoring his ardent advances. Before dinner, he expresses his affections with a song at the piano, “My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose,” words by Robert Burns and melody by James Van Heusen—not by Herrmann, who always pointed out that he was not a “pop” composer. It is Boone’s vocal highlight of the film, although two other Van Heusen songs were cut from the final print; Boone does later manage a few lines from “My Heart’s in the Highlands.”

When Lindenbrook hasn’t arrived for dinner, the guests, including the university’s dean (Alan Napier), visit his laboratory and find him working over the lump of lava. His assistant Paisley (Ben Wright) pours too much aqua regia into the furnace where the professor is attempting to dissolve the lava from whatever heavier object he believes to be inside, and the furnace explodes. The explosion throws everybody to the floor but does separate the lava from what was inside, a plumb bob. On the metal sphere, written in some Nordic language—perhaps in blood—is an inscription and a name, Arne Saknussem, an Icelandic explorer of three hundred years earlier. (In Verne’s novel, the translation came from a runic manuscript.)