An hilarious study in the gentle art of murder.

The British, God bless ’em, are known for their wit, a distorted and sometimes droll wit to many Americans, who don’t always appreciate the extremes of their brand of humor, from subtle double-entendre to farcical broadness.

In the late 1950s, early ’60s, there were the Hoffnung Concerts in which highbrow composers and performers caricatured their own classical music—for example, Malcolm Arnold’s Concerto for Three Vacuum Cleaners and a Floor Polisher. At about the same time the wacky world of Beyond the Fringe erupted to hilarious acclaim in London’s West End and spread to the U.S. All the satire and lampooning of, especially, the arts was thanks to a quartet of comic masters known as Jonathan Miller, Alan Bennett, Dudley Moore and Peter Cook. And then, on BBC TV and later in the movies, there was Monty Python, where comedy became surreal, preposterous, cruel and, yes, sometimes offensive. In this troupe were more than four players, but the best-remembered, the most enduring, are John Cleese and Eric Idle.

For those who would belittle British humor, forget not that many of the most famous of so-called “American” comics and teams—some of them institutions—were wholly, or partly, British: Bob Hope, Laurel and Hardy and Charlie Chaplin.

As America’s Hollywood once held sway, say, in the detective and horror movies, so the British are still masters of the comedy, and turn out more of that genre than their cousins across the Atlantic. Foremost was the “Carry On” series, over thirty low-budget films released between 1958 and 1992, an enterprise dealing in parody, sexual innuendo and the ridicule of the British establishment. The three stars who appeared most frequently throughout the years—Kenneth Williams, Joan Sims and Charles Hawtrey—also performed in conceivably the epitome of the series, Carry On Doctor, with another regular, Barbara Windsor, in another of the scantily-clad roles she made all her own. In this sense, too, the British seemed far ahead of the Americans during the ’50s and ’60s in “coming out” roles for young actresses!

Some British comedies that would be better known to Americans, along with at least one well known star, include The Ghost Goes West (Robert Donat), The Ladykillers (Alec Guinness), A Mouse on the Moon (Margaret Rutherford), Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (Terry-Thomas) and A Fish Called Wanda (Cleese). In more recent releases, the diversity of British humor is further illustrated in Four Weddings and a Funeral, The Full Monty and Chicken Run.

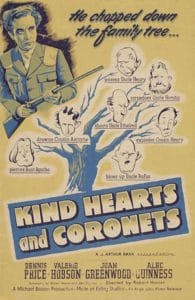

To mention for the first time the intent of all this, there was Kind Hearts and Coronets in 1949, a little masterpiece all its own, a one of a kind. Here, droll humor is at its height, an analytical but comic approach to one of the darker of man’s sins, murder. Even as a school child (Jeremy Spenser), the “hero” and narrator of the story was early on made aware, specifically, of two of the Ten Commandments, two that just happen to be adjacent, the one about not killing, the other about not committing adultery. With already an eye for the little girl next to him, he commented that, at least, he didn’t foresee that he would ever have to worry about the first! A small matter, perhaps.

To mention for the first time the intent of all this, there was Kind Hearts and Coronets in 1949, a little masterpiece all its own, a one of a kind. Here, droll humor is at its height, an analytical but comic approach to one of the darker of man’s sins, murder. Even as a school child (Jeremy Spenser), the “hero” and narrator of the story was early on made aware, specifically, of two of the Ten Commandments, two that just happen to be adjacent, the one about not killing, the other about not committing adultery. With already an eye for the little girl next to him, he commented that, at least, he didn’t foresee that he would ever have to worry about the first! A small matter, perhaps.

There is little in American letters to compare with the often tongue-in-cheek wit, the polished absurdities, of King Hearts and Coronets, certainly not in Poe, whose tales are devoid of humor, nor in the disguised social commentary of Twain’s most famous novels. Rather, the delightful adaptation of Roy Horniman’s novel by screenwriters Robert Hamer (also the director) and John Dighton owes, logically enough, much to one cherished niche of the British literary tradition—the drawing room drama, specifically the writings of Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw and P. G. Woodhouse. Although the link of murder is there, the formula mysteries of Christie are not an influence; they, too, are usually bereft of humor.

On to the plot of Kind Hearts and Coronets——

On to the plot of Kind Hearts and Coronets——

In a prison in Edwardian England, a hangman (Miles Malleson, playing another of his befuddled roles, jowls quivering) arrives to visit what Americans would call the warden (Clive Morton) to see if everything is ready for tomorrow, and to ascertain how to address properly the condemned at the scaffold ceremonies. “Your grace,” he decides, is correct. Louis Mazzini (Dennis Price), if for only the briefest time the Duke of Chalfont, is waiting to be hanged. In the meantime he’s writing his memoirs. Read More