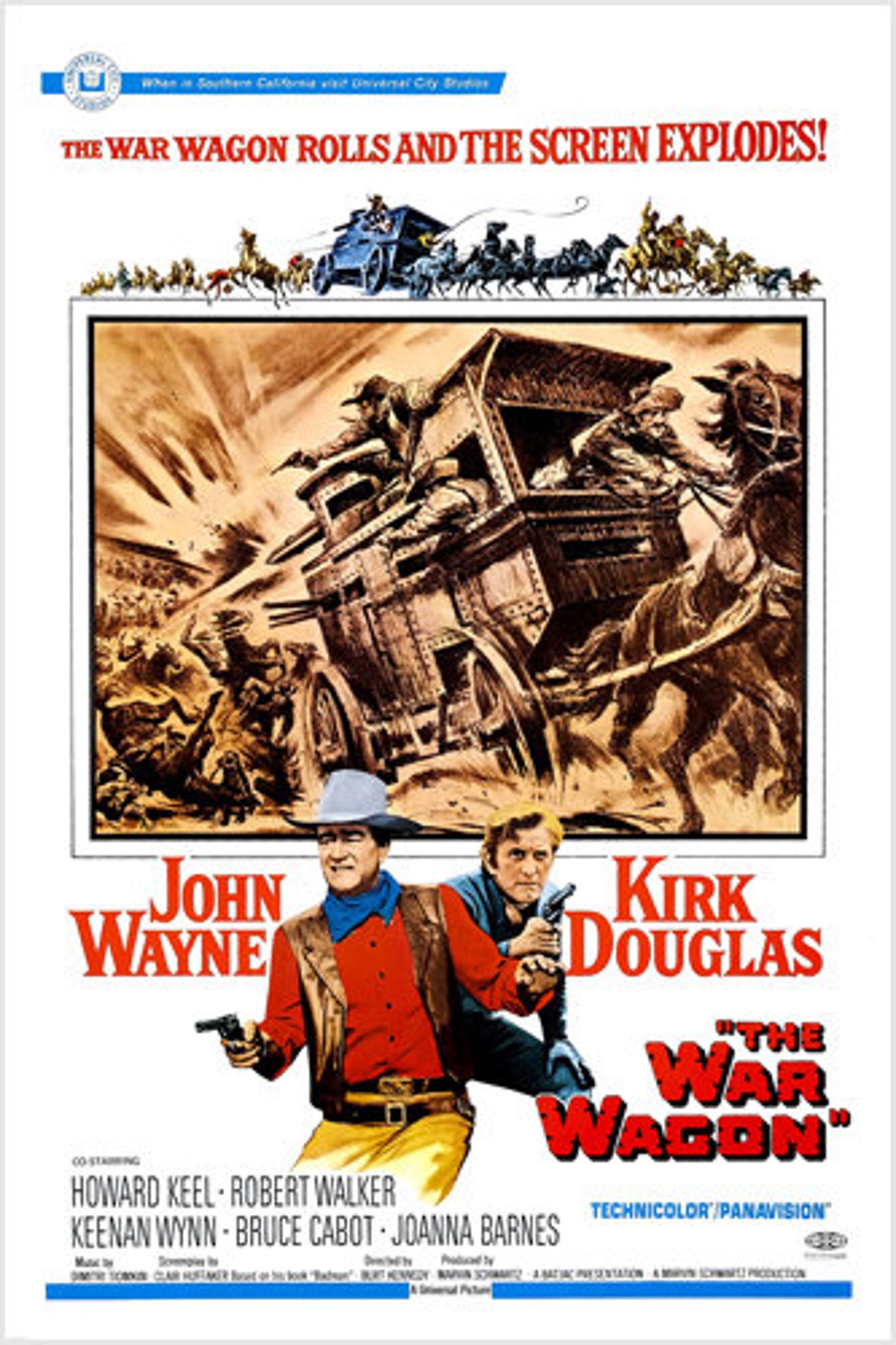

Two enemies call a truce so, together, along with a drunken explosives expert, a born thief and an Indian, they can rob an armored wagon.

Although they could not have known it at the time, for John Wayne and Kirk Douglas The War Wagon would be the last of the three films they made together, and for Dimitri Tiomkin, the composer par excellence of the American Western, the movie would be his last score in that genre.

Even with all the prerequisites and necessary clichés of the standard Western—the saloon brawls, the street shoot-outs, the stagecoach chases, the Indian attacks, the bridge-blowings, the barroom damsels and all the familiar rest (strangely, no train is seen)—Wagon is a tongue-in-cheek, rip-snorter of a caper, mainly owing to the charisma of its two, larger-than-life stars.

The film makes no effort to achieve a place among the great Westerns. Burt Kennedy, a marginal notch above a “B” director, would do his best work when Wagon’s lark-adventure style metamorphoses into unabashed, knock-down, drag-out comedy in Support Your Local Sheriff (1969). Here a team of actors adept at comedy—Harry Morgan, Jack Elam and Walter Brennan—wreak mayhem along with newly-hired sheriff James Garner, an actor skilled in both comic and serious roles.

The film makes no effort to achieve a place among the great Westerns. Burt Kennedy, a marginal notch above a “B” director, would do his best work when Wagon’s lark-adventure style metamorphoses into unabashed, knock-down, drag-out comedy in Support Your Local Sheriff (1969). Here a team of actors adept at comedy—Harry Morgan, Jack Elam and Walter Brennan—wreak mayhem along with newly-hired sheriff James Garner, an actor skilled in both comic and serious roles.

Kennedy is not intimidated by the past, but, rather, in a laid back approach, he is paying a satirical tribute to it in The War Wagon. For there they stand—those genuine masters of the American Western, looming large and seemingly invulnerable.

In making any list, no doubt where to begin. John Ford. From the earliest of the silent days, Ford’s volatile temperament was well suited to the Western. He directed examples of the genre up through his third-to-last-film, though, true, Cheyenne Autumn (1964) is a pale shadow of its creator’s former self. To look back, however, even a partial list of the crème de la crème of the masterpieces must include Stagecoach (1939), My Darling Clementine (1946), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and perhaps the masterpiece, The Searchers (1956).

Apart from the evolution of Ford’s art in the 1940s and ’50s, the period is distinguished by a magnum opus from essentially a non-Western director, a film the critics couldn’t ignore for all their Ford worship. Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948) is now regarded as the first adult Western, a maturity that held true throughout the film until its contrived, about-face happy ending. John Wayne’s harsh portrayal of trail boss Thomas Dunson anticipates his ever harsher racist, Ethan Edwards, in The Searchers.

Apart from the evolution of Ford’s art in the 1940s and ’50s, the period is distinguished by a magnum opus from essentially a non-Western director, a film the critics couldn’t ignore for all their Ford worship. Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948) is now regarded as the first adult Western, a maturity that held true throughout the film until its contrived, about-face happy ending. John Wayne’s harsh portrayal of trail boss Thomas Dunson anticipates his ever harsher racist, Ethan Edwards, in The Searchers.

And then, with the ’50s, arrives possibly the one director who comes the closest to a John Ford facsimile. Though John Sturges lacks Ford’s inborn instincts for the visual and his perfect image-framing, his contributions are worthy markers along the way: Bad Day at Black Rock (1954), albeit a contemporary-set Western; Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), with another Tiomkin song; Last Train from Gun Hill (1958); and The Magnificent Seven (1960).

Bringing Western film history into the ’60s and ’70s, Andrew McLaglen tries awfully hard to be a Ford or Sturges, but falls a little—well, considerably—short of the mark. Possibilities are there but Chisum (1970), Cahill, U.S. Marshal (1973) and The Undefeated (1969)—John Wayne in them all—never bore ripe, much less succulent, fruit, although the last is the best

But McLintock! (1963), McLaglen’s best Western, is several times more tongue-in-cheek than The War Wagon. Both films have John Wayne—both, for that matter, have Wayne’s constant tag-along, Bruce Cabot, hardly a substantial plus—but what makes McLintock! superior, despite Douglas’ absence, is that it has Maureen O’Hara, Wayne’s perfect foil in five films.

But McLintock! (1963), McLaglen’s best Western, is several times more tongue-in-cheek than The War Wagon. Both films have John Wayne—both, for that matter, have Wayne’s constant tag-along, Bruce Cabot, hardly a substantial plus—but what makes McLintock! superior, despite Douglas’ absence, is that it has Maureen O’Hara, Wayne’s perfect foil in five films.

Of course, not to be forgotten, there are a few other basically non-Western directors who make an occasional venture—sometimes two or three—into the world of the cowboy.

The best of these is possibly Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952), though in Marshal Kane’s (Gary Cooper) inability to find citizenry support against approaching outlaws some detect an analogy of the McCarthy hearings and Hollywood’s refusal to wholeheartedly challenge the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The best of these is possibly Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952), though in Marshal Kane’s (Gary Cooper) inability to find citizenry support against approaching outlaws some detect an analogy of the McCarthy hearings and Hollywood’s refusal to wholeheartedly challenge the House Un-American Activities Committee.

A brighter side of the film, and what some say makes it, is Tiomkin’s music. His use of his ballad “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’,” both as a vocal and as an ever-varied tune in the orchestra, revolutionizes film scoring for two decades. In a stroke, Tiomkin discards the opulent nineteenth-century soundtrack style that would not be resurrected until John Williams’ Star Wars (1977).

There is, too, William Wyler’s sprawling, some say overblown, The Big Country (1958) which pits against each other two major stars, Gregory Peck and Charlton Heston, with their different perspectives of life but equal prowess as fist fighters. The specious skies and broad landscapes are brilliantly captured by cinematographer Franz Planer.

And, finally, among the old-fashioned proponents of the Western, Michael Curtiz, in the year of Stagecoach, sets the standard for the barroom brawl in Dodge City (1939), and Raoul Walsh makes fiction more interesting than history in They Died with Their Boots On (1941), both featuring that Tasmanian Western star, Errol Flynn..

And, finally, among the old-fashioned proponents of the Western, Michael Curtiz, in the year of Stagecoach, sets the standard for the barroom brawl in Dodge City (1939), and Raoul Walsh makes fiction more interesting than history in They Died with Their Boots On (1941), both featuring that Tasmanian Western star, Errol Flynn..

Despite their popularity on television in the ’50s and ’60s, the Western declined to “B” level on the big screen. Now comes a plethora of Randolph Scott, Joel McCrea and Audie Murphy surrogates, the film plots largely indistinguishable from one another, making this monotonous and arid creative landscape ripe for cultivation.

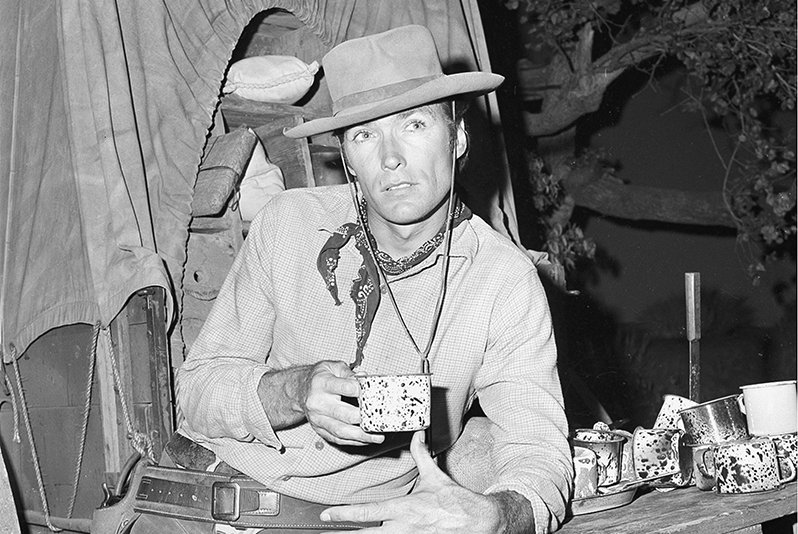

While the wheels of that war wagon were still stirring up dust clouds and Kirk and John were scheming to rob it, the gunslinger of town and plain becomes, now, a loner—cruel, unfeeling, unneedful of a woman, of anybody.

![]() And so it comes to pass that Sergio Leone, in only eight short years, from 1964 to 1971, changes forever the West of the screen, making it, if more true to history, then also as starkly naked, unromantic and violently exaggerated as possible.

And so it comes to pass that Sergio Leone, in only eight short years, from 1964 to 1971, changes forever the West of the screen, making it, if more true to history, then also as starkly naked, unromantic and violently exaggerated as possible.

In A Fistful of Dollars (1964), The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) and other similar films which came to be called “spaghetti Westerns,” Clint Eastwood becomes the new prototype—unemotional, yes, but the loner personified, austere, sauntering across the screen—his pace death itself—largely in silence, his killing aim peerless.

Eastwood is so far the last in the chain of notable Western directors. His films are more or less traditional Westerns—High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) and Pale Rider (1985)—until, inevitably, Leone’s brutality had rubbed off completely in the starkness of The Unforgiven (1992).

The War Wagon begins with Tiomkin’s main title music, a refreshing, open air of French horns, then a harmonica solo. Over a lively string rhythm, a choir sings “Look at those horses, what are they draggin’?” After a stanza, Ed Ames, in his best Western baritone, begins, “Most men are fightin’ for a wagon full of gold/Scaratchin’ an’ fightin’ for a wagon full of gold.” (In High Noon the vocalist is Tex Ritter, in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Frankie Laine.)

The War Wagon begins with Tiomkin’s main title music, a refreshing, open air of French horns, then a harmonica solo. Over a lively string rhythm, a choir sings “Look at those horses, what are they draggin’?” After a stanza, Ed Ames, in his best Western baritone, begins, “Most men are fightin’ for a wagon full of gold/Scaratchin’ an’ fightin’ for a wagon full of gold.” (In High Noon the vocalist is Tex Ritter, in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Frankie Laine.)

On screen during all this, front and center, is the third star of the film, the wagon itself. (It was, for many years, displayed among the movie props on the Universal backlot.) The wagon is an iron-plated stagecoach carrying five armed men, topped by a turreted Gatling gun and pulled by a team of six horses. Ahead and behind it gallop a total of twenty-eight outriders. The wagon regularly transports gold from a mining company owned by the shady Pierce (Cabot) and up-coming is scheduled a million-dollar shipment.

Into town arrives Taw Jackson (Wayne, uncharacteristically as a bad guy), out of prison on good behavior and bent on revenge. Pierce had sent him to prison and stolen his ranch. Years before, Lomax (Douglas, in his eleventh Western) had shot Jackson, and now when the two men meet again, he brags, “You’re the only man ever shot I didn’t kill.”

Into town arrives Taw Jackson (Wayne, uncharacteristically as a bad guy), out of prison on good behavior and bent on revenge. Pierce had sent him to prison and stolen his ranch. Years before, Lomax (Douglas, in his eleventh Western) had shot Jackson, and now when the two men meet again, he brags, “You’re the only man ever shot I didn’t kill.”

Although Pierce has paid Lomax $12,000 to kill his old enemy, Jackson offers him a $100,000 share from a planned war wagon robbery. They will be joined in the scheme by alcoholic Billy Hyatt (Robert Walker, Jr.), an explosives expert; an Indian, Levi Walking Bear (Howard Keel), joined by members of his tribe; and Wes Fletcher (Keenan Wynn), a greedy old man who is even stealing before the robbery.

Timing in the scheme is essential. Massed Indians, dragging tree limbs to stir up dust, will create a diversion, drawing the outriders away from the wagon. A second band of Indians will attack the wagon. Once the fleeing wagon crosses a bridge, the structure will be dynamited by Billy, isolating the outriders should they try to pursue. Finally, as the wagon negotiates a pass, a huge tree trunk suspended on ropes will swing down and decapitate the turret and its gun from the wagon. At least that’s the plan.

Timing in the scheme is essential. Massed Indians, dragging tree limbs to stir up dust, will create a diversion, drawing the outriders away from the wagon. A second band of Indians will attack the wagon. Once the fleeing wagon crosses a bridge, the structure will be dynamited by Billy, isolating the outriders should they try to pursue. Finally, as the wagon negotiates a pass, a huge tree trunk suspended on ropes will swing down and decapitate the turret and its gun from the wagon. At least that’s the plan.

It works only marginally well. Pierce, inside the wagon, is killed along with his guards. That suits Jackson, but the wagon overturns in a ravine. While the bagged gold is being hidden in barrels of flour on Fletcher’s wagon, he is killed by a band of Kiowa Indians. Then the Indians, who want the flour, steal the wagon.

From what little gold is recovered, Jackson gives some to Billy and tells Lomax that the rest he has hidden and it will be divided in six months when the holdup’s notoriety has died down. Jackson tells Lomax he’d better make sure nothing happens to him in the meantime.

From what little gold is recovered, Jackson gives some to Billy and tells Lomax that the rest he has hidden and it will be divided in six months when the holdup’s notoriety has died down. Jackson tells Lomax he’d better make sure nothing happens to him in the meantime.

John Wayne and Kirk Douglas were as diverse in their politics as they were in their different physical conditions during the filming of The War Wagon. Wayne was much older in body than his sixty years, having had a lung removed in 1964 and dependent upon oxygen. Douglas was an agile fifty, with a half-century yet to live, vaulting onto horses, twirling revolvers, jumping onto stagecoaches, swinging from chandeliers and leaping fences.

Once the miscasting of Howard Keel is accepted—he is dryly funny as an Indian—everyone does their bit with conviction, including Keenan Wynn, usually playing grisly old men by this time, and Robert Walker whose career faded after an encouraging start. His own words became ironically prophetic: “I would like to develop as an actor in obscurity.”

The War Wagon is well worth seeing. In tempo, it only occasionally sags. In action, there is enough to hold the attention of most audiences. If it lacks the scenic splendor of John Ford—there’s that name again!—cinematographer William H. Clothier delivers crisp and dynamic screen images.

The War Wagon is well worth seeing. In tempo, it only occasionally sags. In action, there is enough to hold the attention of most audiences. If it lacks the scenic splendor of John Ford—there’s that name again!—cinematographer William H. Clothier delivers crisp and dynamic screen images.

He had shot the Wayne-directed The Alamo (1960), Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), McLaglen’s McLintock! and countless other Westerns, including many more of John Ford’s. As something of a tie-in with all the preceding, Clothier retired in 1972 after shooting The Train Robbers—a Wayne Western and directed by Burt Kennedy.

And, if nothing else, there’s always Tiomkin’s buoyant score—and its main tune/song.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jTevqyP8hPA [/embedyt]