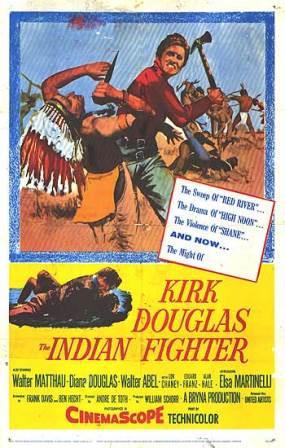

The Indian Fighter and the Girl…a love as fierce as a fire arrow!

Kirk Douglas was likely at his peak in the mid-1950s. Taking a cue from Burt Lancaster, Douglas set up Bryna Productions, his own production company. Their first production was 1955’s The Indian Fighter.

The Indian Fighter is an interesting film for what it tries to be, though it fails in many areas and becomes a standard (and rather placid) western. Douglas stars (of course) as the “Indian Fighter” Johnny Hawks, serving throughout as a go between of sorts between the Sioux Nation and the U.S. cavalry fort nearby. The root of most of the conflict of the movie is caused by two cretins, Chivington and Wes (played by Lon Chaney Jr. and Walter Matthau, respectively), who constantly work to discover the hidden location of the Sioux’s “yellow iron,” better known as gold.

Chief Red Cloud (Eduard Franz) has prohibited any of his people from sharing the location on penalty of death, which applies also to his daughter Onahti (Elsa Martinelli). Red Cloud is enlightened enough to realize the problems the gold creates and chooses mostly to leave the gold and its related problems in the ground.

Overall the picture is well produced and has quite a bit of intelligent thought behind it. It’s among a string of westerns where Native Americans are depicted as intelligent, though provoking and three dimensional characters. Red Cloud’s concern for the environment and long-term perspective are admirable and engaging. When things start to fly later on in the finale, their strategy is perhaps among the most creative of the time, with riders dragging brush behind their horses to both disguise their movements and cloud the vision of the cavalry defenders. Attacking the fort with fire rather than just charging it also shows great vision. Your standard run of the mill cannon fodder these Sioux are not!

Overall the picture is well produced and has quite a bit of intelligent thought behind it. It’s among a string of westerns where Native Americans are depicted as intelligent, though provoking and three dimensional characters. Red Cloud’s concern for the environment and long-term perspective are admirable and engaging. When things start to fly later on in the finale, their strategy is perhaps among the most creative of the time, with riders dragging brush behind their horses to both disguise their movements and cloud the vision of the cavalry defenders. Attacking the fort with fire rather than just charging it also shows great vision. Your standard run of the mill cannon fodder these Sioux are not!

Johnny Hawks (Douglas) has a relationship with Onahti, the Chief’s daughter in a very early (and rather obvious) display of mixed-race relationships. For all his fame as an “Indian fighter” it’s clear somewhat early on that fighting isn’t his preference. In fact he fights rather little and usually makes it appoint to try to reason away conflicts and only fights when absolutely needed.

But as enlightened as The Indian Fighter, it comes with a price. Hawks’ relationship with Onahti starts off with what can only be termed a (near) rape. It seems hard to find any realism in her eventually coming around to his way of thinking or- an even greater stretch of the imagination- that Red Cloud would stand for that type of treatment of his daughter. Though much less so than in other films, there’s still some stereotypical depictions of Native Americans, most notably during a trading scene when a warrior with fresh game initially it looking to trade his kill for beans but is mesmerized by the potential for a trade for booze, of which he immediately gets roaring drunk on.

But as enlightened as The Indian Fighter, it comes with a price. Hawks’ relationship with Onahti starts off with what can only be termed a (near) rape. It seems hard to find any realism in her eventually coming around to his way of thinking or- an even greater stretch of the imagination- that Red Cloud would stand for that type of treatment of his daughter. Though much less so than in other films, there’s still some stereotypical depictions of Native Americans, most notably during a trading scene when a warrior with fresh game initially it looking to trade his kill for beans but is mesmerized by the potential for a trade for booze, of which he immediately gets roaring drunk on.

Sadly there is so much thought given to “deeper thought” by director Andre de Toth that the plot seems to take a back seat to the sermonizing (as well intended as it is). As a result the conflict seems out of proportion with the reality of these two rather unimaginative would be gold thieves creating a full out war.

Matthau and Chaney as the heavies are at least part of the problem. Though perhaps hindsight is overly beneficial now, Matthau seems horribly miscast as the lead of his little two man gang. He just doesn’t seem mean or conniving enough to be convincing, evincing some of the softness perhaps that would serve him better latter in his career. Chaney’s rather a non-entity, given little of note to do except follow Matthau’s lead. Sadly, this was a trend for much of Chaney’s career.

Matthau and Chaney as the heavies are at least part of the problem. Though perhaps hindsight is overly beneficial now, Matthau seems horribly miscast as the lead of his little two man gang. He just doesn’t seem mean or conniving enough to be convincing, evincing some of the softness perhaps that would serve him better latter in his career. Chaney’s rather a non-entity, given little of note to do except follow Matthau’s lead. Sadly, this was a trend for much of Chaney’s career.

Elsa Martinelli is surprisingly effective, though it’s clear that her native language (Italian) does interfere a bit in the proceedings. She was discovered by Douglas’ wife to star in the film, in which Douglas’ ex-wife Diana also plays a small roll as single mother Susan Rogers. Ironically she and Kirk were having a torrid affair throughout filming, which Douglas admitted to in his autobiography many years later.

Douglas himself is, well, Douglas. An extremely talented actor, he usually did his best work playing against another strong lead. In The Indian Fighter, like other similar films where there isn’t a strong co-star to mute (or more likely challenge Douglas to bring his best stuff) Douglas, the star comes off with a smugness that borders on arrogance. His character seems more of an “Indian Lover” than an “Indian Fighter,” as mentioned earlier.

Douglas himself is, well, Douglas. An extremely talented actor, he usually did his best work playing against another strong lead. In The Indian Fighter, like other similar films where there isn’t a strong co-star to mute (or more likely challenge Douglas to bring his best stuff) Douglas, the star comes off with a smugness that borders on arrogance. His character seems more of an “Indian Lover” than an “Indian Fighter,” as mentioned earlier.

Granted, he’s still effective, but his performance would have benefited from a stronger cast around him, most notably a bigger star in Matthau’s role. This would not only have challenged Douglas but also created the tension and real conflict to make the story work. As is, it’s a bit challenging not to see either Matthau or Chaney simply executed by one side or the other.

The best parts of The Indian Fighter is the realistic depiction of Native Americans, which is fairly faithfully done with the exception of placing the Sioux in Oregon. So instead of the Great Plains we get the northwest, which is gorgeously shot by Wilfred Cline in Cinemascope. A competent if barely memorable Franz Waxman score also helps the picture become a strong if rather unfulfilling experience.